The Viable But Non-Culturable (VBNC) State in Bacteria: A Comprehensive Guide to Mechanisms, Detection, and Clinical Implications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the bacterial Viable But Non-Culturable (VBNC) state, a dormant survival strategy with profound implications for public health, clinical diagnostics, and drug development.

The Viable But Non-Culturable (VBNC) State in Bacteria: A Comprehensive Guide to Mechanisms, Detection, and Clinical Implications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the bacterial Viable But Non-Culturable (VBNC) state, a dormant survival strategy with profound implications for public health, clinical diagnostics, and drug development. We explore the fundamental biological characteristics and induction mechanisms of VBNC cells, detail advanced methodological approaches for their detection and quantification, address critical challenges in distinguishing VBNC states from similar phenomena, and evaluate their validated role in antibiotic resistance and virulence retention. Synthesizing current research, this review aims to equip researchers and pharmaceutical professionals with the knowledge to develop novel strategies to counteract the risks posed by these elusive bacterial populations.

Unveiling the Stealth Survival Strategy: Fundamentals of the VBNC State

The Viable but Non-Culturable (VBNC) state represents a fundamental survival strategy adopted by numerous bacterial species when confronted with unfavorable environmental conditions. Cells in this state are characterized by a profound contradiction: they are metabolically active and maintain membrane integrity, yet cannot form colonies on conventional growth media typically used for their cultivation [1] [2]. This phenomenon challenges the traditional microbiological paradigm that equates culturability with viability, necessitating a revision of how we define and detect living bacteria.

First proposed in 1982, the VBNC concept has since been identified in over 100 bacterial species across diverse genera [3] [4]. This state is not a precursor to cell death but rather a dormancy strategy that allows bacteria to persist through stressful conditions while retaining the potential to resuscitate when conditions improve [5]. The study of the VBNC state has significant implications for public health, food safety, clinical microbiology, and environmental science, as standard culture-based methods fail to detect these potentially pathogenic organisms [2].

Defining Characteristics and Molecular Basis

Diagnostic Criteria for the VBNC State

The VBNC state is defined by three primary characteristics that distinguish it from other physiological states such as dormancy, persistence, or cell death:

- Loss of Culturability: The inability to form colonies on standard laboratory media that normally support growth of the bacterium, despite maintaining viability [4].

- Metabolic Activity: Continued, albeit reduced, metabolic processes evidenced by ATP production, nutrient transport, respiration, and gene expression [1] [2].

- Resuscitation Capability: The capacity to return to a culturable state upon removal of the inducing stressor or application of specific resuscitation signals [5] [2].

Distinguishing VBNC from Related States

The VBNC state is often confused with other non-growing bacterial states. The table below clarifies the key distinctions:

Table 1: Differentiation Between VBNC State and Related Physiological States

| Physiological State | Culturability | Metabolic Activity | Resuscitation Conditions | Primary Inducers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VBNC | Lost | Measurably active | Requires specific stimuli (often different from original growth conditions) | Multiple environmental stresses |

| Dormancy | Variable | Below detection limit | Restoration of permissive conditions | Nutrient limitation |

| Persister Cells | Retained | Reduced | Removal of antibiotic | Antibiotic treatment |

| Dead Cells | Lost | None | Not possible | Lethal damage |

Cellular and Molecular Adaptations

Upon entering the VBNC state, bacteria undergo significant morphological and physiological transformations:

- Reduced Cell Size: Cells typically become smaller and spherical in shape [1].

- Metabolic Downregulation: Drastic reduction in nutrient transport, respiration rates, and macromolecular synthesis [1].

- Membrane Modifications: Changes in fatty acid composition and increased cross-linking in peptidoglycan layers [2].

- Gene Expression Continuity: Despite metabolic reduction, VBNC cells maintain selective gene expression, including continued transcription of virulence genes in pathogens [2] [4].

- Enhanced Stress Resistance: VBNC cells demonstrate increased resistance to antibiotics, disinfectants, and additional environmental challenges [6].

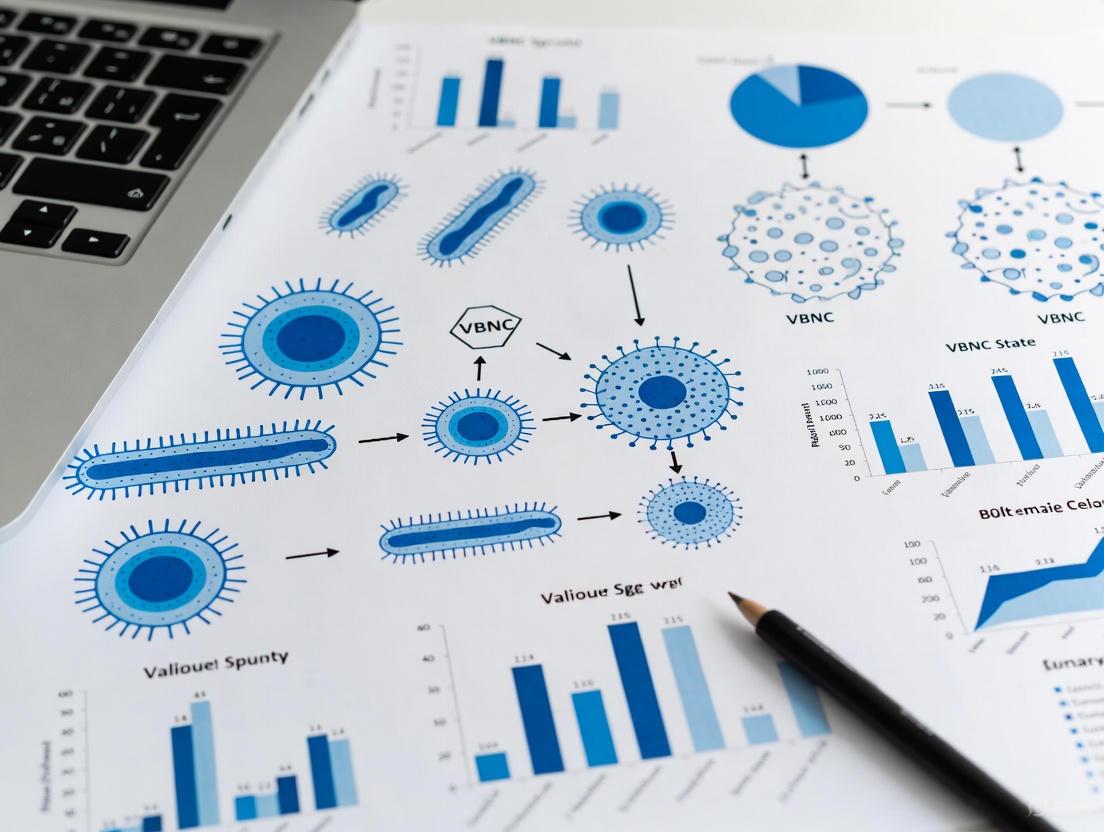

The following diagram illustrates the transition between cellular states and the defining characteristics of the VBNC state:

Diagram 1: Bacterial State Transitions and VBNC Characteristics

Environmental Inducers of the VBNC State

Multiple environmental stressors can trigger the transition into the VBNC state. The table below summarizes major inducing factors and their effects on various bacterial species:

Table 2: Environmental Factors Inducing the VBNC State in Various Bacterial Species

| Inducing Factor | Example Organisms | Experimental Conditions | Time to VBNC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrient Starvation | Vibrio cholerae, E. coli | Artificial seawater, minimal media | Days to weeks |

| Temperature Extremes | Campylobacter jejuni, Listeria monocytogenes | 4°C incubation | 15-30 days |

| Oxidative Stress | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Chlorine (1-3 mg/L) | 5-30 minutes |

| Osmotic Stress | Salmonella Oranienburg | High NaCl concentrations | 48 hours |

| Acidic Conditions | Campylobacter jejuni | pH 4.0 | 2 hours |

| UV Radiation | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 245 nm wavelength | 1-30 minutes |

| Food Preservatives | Listeria monocytogenes | Potassium sorbate (pH 4.0) | 24 hours |

| Heavy Metals | E. coli | Copper, cadmium solutions | Hours to days |

Resuscitation from the VBNC state occurs when appropriate conditions are restored or specific signals are received:

- Temperature Upshift: Increasing temperature from stressful to permissive levels can trigger resuscitation [5].

- Nutrient Supplementation: Addition of specific nutrients, sometimes including reactive oxygen species neutralizers like sodium pyruvate [5].

- Host Passage: VBNC pathogens often resuscitate upon entering appropriate host environments [2].

- Quorum Sensing Signals: Some evidence suggests cell-to-cell communication molecules may facilitate resuscitation [4].

- Removal of Stressors: Simply eliminating the inducing stressor may allow resuscitation in some cases [7].

The complexity of resuscitation is highlighted by findings that VBNC cells induced by different stressors may exhibit varying resuscitation capabilities. For example, UV-induced VBNC P. aeruginosa resuscitated more quickly than those induced by chlorine disinfection [7].

Detection Methodologies and Technical Approaches

Limitations of Conventional Culture Methods

Traditional microbiological detection relying on colony formation on solid media fails completely to detect VBNC cells, leading to significant underestimation of viable bacterial populations in clinical, environmental, and food samples [2]. This limitation poses serious challenges for public health protection, as pathogens in the VBNC state retain virulence and can resuscitate to cause infections [2] [4].

Advanced Detection Techniques

Multiple culture-independent approaches have been developed to detect and quantify VBNC cells:

Viability Staining and Flow Cytometry

This approach utilizes fluorescent dyes that differentiate between cells with intact and compromised membranes:

- SYTO 9 and Propidium Iodide (PI): The LIVE/DEAD BacLight bacterial viability kit stains all cells with SYTO 9 (green fluorescence), while PI (red fluorescence) penetrates only cells with damaged membranes [8].

- Methodology: Stained cells are analyzed by flow cytometry to distinguish between viable (SYTO 9 positive only) and dead (PI positive) populations.

- Limitations: This method can overestimate viability in complex matrices like food samples or process wash water due to interference from particulate matter [8].

Viability PCR (v-PCR) Techniques

Molecular methods combined with viability markers represent the most advanced approach for VBNC detection:

- PMA (Propidium Monoazide) and PMAxx: These DNA-intercalating dyes penetrate cells with compromised membranes and covalently bind to DNA upon photoactivation, preventing PCR amplification [8] [9].

- EMA (Ethidium Monoazide): Similar to PMA but with higher cytotoxicity toward viable cells, potentially leading to false positives [8].

- Optimized Protocol: Recent studies demonstrate that combining EMA (10 μM) and PMAxx (75 μM) with incubation at 40°C for 40 minutes followed by 15-minute light exposure effectively inhibits PCR amplification from dead cells while allowing detection of VBNC cells [8].

Molecular Quantification Methods

- qPCR (Quantitative PCR): Following PMA treatment, qPCR targets specific genes to quantify viable cells [9] [7].

- ddPCR (Droplet Digital PCR): This emerging technology provides absolute quantification without standard curves by partitioning samples into thousands of nanoliter droplets [9] [10]. Recent studies have optimized PMA concentration (5-200 μM) and incubation time (5-30 minutes) for accurate VBNC cell quantification [9].

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental workflow for VBNC state detection and quantification:

Diagram 2: VBNC Detection Methodological Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for VBNC State Investigation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viability Dyes | PMA, PMAxx, EMA | Differentiate cells based on membrane integrity | PMAxx shows improved performance over PMA; EMA may cause false positives |

| Nucleic Acid Stains | SYTO 9, Propidium Iodide (PI) | Membrane integrity assessment via fluorescence | Used in combination for flow cytometry |

| Culture Media | LB broth/agar, BHI broth, ASW | Culturability assessment and resuscitation studies | Artificial Sea Water (ASW) used for VBNC induction |

| PCR Reagents | Primers (rpoB, adhE, KP), polymerases | Gene-targeted quantification of viable cells | Target single-copy genes for accurate quantification |

| Disinfection Agents | Sodium hypochlorite, peracetic acid | Inducing VBNC state in experimental systems | Sodium thiosulfate used to quench disinfectants |

| Antibiotics | Ciprofloxacin, polymyxin | Studying VBNC state resistance and resuscitation inhibition | Ciprofloxacin inhibits VBNC cell recovery |

Research Implications and Future Directions

The recognition of the VBNC state has profound implications across multiple scientific disciplines:

- Clinical Microbiology: VBNC pathogens may explain recurrent infections and culture-negative diagnostic results, particularly in cases like urinary tract infections where VBNC E. coli demonstrates antibiotic resistance [2].

- Food Safety: Routine food testing may fail to detect VBNC pathogens, creating false assurances of safety, as demonstrated in outbreaks linked to VBNC E. coli and Salmonella [5] [2].

- Water Treatment: Disinfection processes using chlorine, UV, or peracetic acid may induce VBNC states in pathogens rather than eliminating them, potentially leading to post-treatment resuscitation [7].

- Antimicrobial Development: VBNC cells exhibit enhanced resistance to antimicrobial agents, necessitating novel approaches that target these persistent populations [6].

Future research priorities include standardizing detection methodologies across different bacterial species and matrices, elucidating the genetic regulation of VBNC entry and exit, and developing interventions that specifically target VBNC cells to prevent resuscitation and disease transmission. The integration of advanced molecular techniques like ddPCR with optimized viability staining provides promising avenues for more accurate detection and quantification of these elusive bacterial populations.

Key Inducing Stresses in Clinical and Environmental Settings

The viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state is a unique survival strategy adopted by numerous bacterial species when confronted with unfavorable environmental conditions [11]. In this state, cells lose the ability to form colonies on conventional culture media—the standard method for detecting viability in microbiology laboratories—while maintaining metabolic activity and cellular integrity [12] [11]. This phenomenon presents substantial challenges for public health, clinical diagnostics, and food safety, as VBNC pathogens can evade detection while retaining virulence potential and resuscitating when conditions improve [13] [12].

Understanding the specific stressors that trigger this dormant state is crucial for multiple disciplines. In clinical settings, VBNC formation may contribute to persistent and recurrent infections, while in industrial and environmental contexts, it compromises the efficacy of sterilization and monitoring protocols [14] [7]. This technical guide synthesizes current research on key inducing stresses across clinical and environmental settings, providing detailed experimental data and methodologies to advance VBNC state research.

Key Inducing Stresses for the VBNC State

Bacteria enter the VBNC state as a survival response to various physicochemical stresses. The table below summarizes the primary inducing factors identified in recent research, along with their effective thresholds for representative bacterial species.

Table 1: Key Stressors Inducing the VBNC State in Various Bacterial Pathogens

| Stress Category | Specific Stressor | Bacterial Species | Effective Concentration/Duration | Experimental Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Disinfectants | Sodium hypochlorite (Chlorine) | Listeria monocytogenes | 37.5 ppm for 10 min [13] | 20°C in laboratory medium [13] |

| Sodium hypochlorite | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 1-3 mg/L for 5-30 min [7] | Drinking water, room temperature [7] | |

| Sodium dichloroisocyanurate | Listeria monocytogenes | 50-75 ppm for 10 min [13] | 20°C in laboratory medium [13] | |

| Hydrogen Peroxide | Listeria monocytogenes | 12,000 ppm for 10 min [13] | 20°C in laboratory medium [13] | |

| Peracetic Acid (PAA) | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 40 μM for 30 min [7] | Drinking water, room temperature [7] | |

| Food Preservatives | Potassium Sorbate | Listeria monocytogenes | pH 2.0 for 10 min [13] | 20°C in laboratory medium [13] |

| Physical Stresses | UV Radiation | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 245 nm wavelength for 30 min [7] | Drinking water, room temperature [7] |

| Low Temperature | Shigella flexneri | 4°C for 19-24 days [15] | Distilled water with varying NaCl concentrations [15] | |

| Osmotic Stress | Sodium Chloride (NaCl) | Shigella flexneri | 0-30% solutions at 4°C [15] | Incubation until loss of cultivability (19-24 days) [15] |

| Nutritional Stress | Starvation in Distilled Water | Shigella flexneri | 4°C for 19 days [15] | Distilled water without nutrients [15] |

Analysis of Key Stress Categories

Chemical Disinfectants: Oxidizing agents like chlorine and hydrogen peroxide are particularly effective at inducing the VBNC state. These compounds cause damage to cellular components, leading to a loss of culturability while membrane integrity may be preserved [13] [7]. Different serotypes of Listeria monocytogenes (1/2a, 4b, 1/2c, 4d) showed varying resilience but ultimately entered the VBNC state when exposed to chlorine-based disinfectants [13].

Physical Stresses: UV radiation effectively damages bacterial DNA, leading to a loss of replicative capacity while maintaining metabolic activity [7]. Low temperature, especially refrigeration temperatures (4°C), significantly prolongs bacterial survival in the VBNC state, particularly when combined with other stresses like osmotic pressure [15].

Osmotic and Nutritional Stress: The combination of low temperature and high salt concentrations creates a potent inducing environment, as demonstrated in Shigella flexneri [15]. Nutrient deprivation in minimal aqueous environments forces bacteria to dramatically reduce their metabolic activity to survive extended periods [15].

Experimental Protocols for VBNC Induction and Detection

- Bacterial Strain and Preparation: Shigella flexneri ATCC 12022 is prepared to 0.5 McFarland standard turbidity.

- Stress Application:

- Prepare NaCl solutions across a concentration gradient (0%, 5%, 10%, 15%, 20%, 25%, 30%).

- Inoculate 100 μL of bacterial suspension into 4.9 mL of each salt solution.

- Incubate at 4°C. Perform six biological replicates for statistical rigor.

- Culturability Assessment:

- Daily subculturing onto Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) agar enriched with 0.6% yeast extract and 1% sodium pyruvate.

- Incubate subcultured plates at 37°C for 16-24 hours.

- The VBNC state is considered induced when no bacterial colonies are observed on the BHI medium after incubation.

- VBNC State Confirmation:

- RNA Extraction and RT-PCR: Extract RNA from pelleted cells and perform reverse transcription. Amplify virulence genes (ipaH and ipaD) via PCR to confirm metabolic activity and viability.

- Fluorescence Microscopy: Centrifuge non-culturable samples, wash with PBS, and stain. Use untreated bacteria and ethanol-killed bacteria as positive and negative controls, respectively.

- Bacterial Cultivation and Disinfection:

- Culture P. aeruginosa in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium to logarithmic phase.

- Centrifuge, wash, and resuspend in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

- Apply disinfectant stresses:

- UV: Expose in Petri dish to 245 nm UV light for timed intervals.

- Chlorine: Add NaClO (0.5-3 mg/L) and quench with sodium thiosulfate at timed intervals.

- Peracetic Acid: Add PAA (40 μM) and quench with sodium thiosulfate.

- Viable Cell Quantification via PMA-qPCR:

- PMA Treatment: Add PMA dye to samples, incubate in the dark for 5 minutes, then expose to a 650 W halogen light source on ice for 5 minutes.

- DNA Extraction and qPCR: Filter treated samples, extract DNA, and perform qPCR targeting specific genes.

- Calculation of VBNC Cells: Subtract the number of culturable cells (CFU/mL) from the number of viable cells (determined by PMA-qPCR) to quantify the VBNC population.

- Resuscitation Potential Assessment:

- Incubate VBNC cell suspensions in LB medium at 37°C with shaking.

- Sample bihourly and plate on nutrient agar to monitor the return of culturability.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the core experimental and detection process for the VBNC state:

Advanced Detection Methodologies

Accurate detection of VBNC cells is technically challenging as they are invisible to standard plating methods. The following table compares key modern detection techniques.

Table 2: Methodologies for Detecting and Confirming the VBNC State

| Method Category | Specific Technique | Principle | Key Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Viability Testing | PMA/Dye-based qPCR (v-qPCR) | PMA penetrates dead cells with compromised membranes, binding to DNA and inhibiting its amplification in PCR. Primers target specific virulence or housekeeping genes [16] [7] [17]. | Detection in complex water matrices (PWW) [17], fecal samples [16], drinking water [7]. | Can overestimate if dead cells have intact membranes; requires optimization for each matrix [17]. |

| Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) | Partitions sample into thousands of droplets for absolute quantification of target genes without a standard curve. Often combined with PMA (PMA-ddPCR) [16]. | Absolute quantification of viable cells, especially with low concentrations (e.g., in fecal samples) [16]. | Highly precise, does not require external standard curve; uses single-copy genes (e.g., rpoB, adhE) [16]. | |

| Cell Staining & Cytometry | Live/Dead Fluorescence Staining & Microscopy | Uses fluorescent dyes to distinguish cells with intact (live/VBNC) vs. damaged (dead) membranes [15]. | Direct visualization and confirmation of VBNC state in laboratory cultures [15]. | Can be subjective; may not be suitable for complex, particulate-laden samples like PWW [17]. |

| Flow Cytometry | Automates the analysis of fluorescently stained cells, providing population-level data on viability [17]. | High-throughput analysis of bacterial viability in pure suspensions. | Can overestimate dead cells in complex matrices like PWW due to interference [17]. | |

| Metabolic & Virulence Activity | Reverse Transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) | Detects messenger RNA (mRNA), which has a short half-life, confirming ongoing metabolic activity and gene expression in VBNC cells [15]. | Confirming viability and expression of virulence genes (e.g., ipaH, ipaD in S. flexneri) [15]. | Technically demanding due to RNA instability; confirms metabolic activity. |

| Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP) Assay | Measures intracellular ATP levels as an indicator of metabolic activity [13] [7]. | Assessing metabolic activity of VBNC cells post-disinfection [7]. | Correlates with metabolic activity but does not confirm virulence. |

Optimized Detection Protocol for Complex Matrices

For accurate detection in complex matrices like process wash water (PWW) from the food industry, an optimized v-qPCR protocol has been validated [17]:

- Sample Treatment: Combine EMA (10 μM) and PMAxx (75 μM) dyes.

- Incubation: Incubate at 40°C for 40 minutes, followed by a 15-minute light exposure.

- Rationale: This dual-dye approach at elevated temperature more effectively penetrates and inhibits DNA amplification from dead cells, reducing false positives and providing a more reliable count of VBNC cells in challenging environments.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for VBNC State Research

| Item Name | Specification/Example | Primary Function in VBNC Research |

|---|---|---|

| Viability Dyes | Propidium Monoazide (PMA/PMAxx) [17] | DNA intercalator that penetrates only dead cells with compromised membranes, inhibiting PCR amplification. |

| Ethidium Monoazide (EMA) [17] | DNA intercalator often used in combination with PMA for enhanced exclusion of dead cell DNA. | |

| Nucleic Acid Kits | RNA Extraction Kit (e.g., DENA Zist Asia) [15] | Isolates high-quality RNA for RT-PCR to confirm metabolic activity via mRNA detection. |

| cDNA Synthesis Kit [15] | Converts extracted RNA to complementary DNA (cDNA) for subsequent PCR amplification. | |

| Culture Media | Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) with supplements [15] | Enriched medium used for checking cultivability; yeast extract and sodium pyruvate can aid recovery of stressed cells. |

| Luria-Bertani (LB) Broth/Agar [16] [7] | Standard medium for culturing and resuscitating bacteria like P. aeruginosa and K. pneumoniae. | |

| Chemical Stressors | Sodium Hypochlorite (NaClO) [13] [7] | Common disinfectant used to induce the VBNC state in laboratory experiments. |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) [13] | Oxidative stressor used to trigger the VBNC state. | |

| Buffers & Solutions | Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) [7] [15] | Used for washing and resuspending bacterial cells without causing osmotic shock. |

| Artificial Seawater (ASW) [16] | Defined medium used for VBNC induction under low-nutrient conditions. | |

| qPCR/ddPCR Reagents | Primer Sets for target genes (e.g., rpoB, adhE, KP) [16] | Target specific single-copy genes in the bacterial genome for precise quantification. |

| Premix Ex Taq or similar Master Mix [16] [15] | Optimized cocktail for efficient and specific PCR amplification. |

The induction of the VBNC state by common clinical and environmental stresses represents a significant and underappreciated challenge in microbiology. Chemical disinfectants, physical processes, and natural stressors can trigger this survival state, allowing pathogens to evade detection and potentially resuscitate to cause infections. Moving forward, research must focus on elucidating the genetic and molecular mechanisms governing the VBNC transition and resuscitation. Furthermore, the development of robust, standardized detection methods that can be widely implemented in clinical, industrial, and regulatory settings is paramount to accurately assess risk and develop effective strategies to combat persistent VBNC pathogens.

Cellular and Molecular Hallmarks of VBNC Entry

The viable but nonculturable (VBNC) state is a unique survival strategy employed by many bacteria when confronted with adverse environmental conditions [1] [18]. In this dormant state, bacteria lose the ability to form colonies on routine culture media—the cornerstone of conventional microbiology—yet remain alive with measurable metabolic activity and intact cell membranes [1] [2]. The VBNC state represents a significant public health concern, as pathogenic bacteria in this state cannot be detected by standard plating methods but retain virulence and can resuscitate under favorable conditions, leading to potential disease outbreaks [18] [2]. Since its initial discovery in Escherichia coli and Vibrio cholerae in 1982, over 100 bacterial species have been documented to enter this physiological state [18]. Understanding the cellular triggers and molecular mechanisms governing entry into the VBNC state is therefore crucial for multiple fields, including clinical microbiology, food safety, and public health. This technical guide synthesizes current knowledge on the hallmarks of VBNC entry, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for studying this complex bacterial adaptation.

Inducing Conditions and Quantitative Thresholds

Bacteria enter the VBNC state in response to a diverse array of environmental stresses. The table below summarizes the primary inducing factors and their documented effects on various bacterial species.

Table 1: Environmental Conditions Inducing the VBNC State and Their Documented Effects

| Inducing Condition | Specific Stressors | Example Affected Species | Quantifiable Effects | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Stresses | Low temperature (e.g., 4°C) | Vibrio vulnificus, E. coli O157:H7, Staphylococcus aureus | Induced after 18 days in S. aureus with citric acid and low temperature [18]. | Artificial seawater, food models [18] [19]. |

| UV Radiation | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | >99.9% reduction in culturability; majority enter VBNC state [7]. | Drinking water disinfection [7]. | |

| Desiccation | Pseudomonas putida KT2440 | Induced as a survival strategy [1]. | Laboratory microcosm [1]. | |

| Chemical Stresses | Nutrient Starvation | E. coli, Shigella dysenteriae, Klebsiella pneumoniae | Common in oligotrophic environments like water systems [18] [2]. | Artificial seawater, tap water microcosms [18]. |

| Chlorination (NaClO) | P. aeruginosa, Listeria monocytogenes | >99.9% reduction in culturability; evident membrane disruption [18] [7]. | Drinking water disinfection, food processing [18] [7]. | |

| Extreme pH (acidic/alkaline) | E. coli O157:H7, S. aureus | Induced under both acidic and alkaline pH conditions [18]. | Food models (e.g., fruit juices) [18] [2]. | |

| Food Preservatives & Essential Oils | Listeria monocytogenes, Vibrio vulnificus | Induced by citral at 4MIC (160 μL/L) treatment for 4.5h [20]. | Seafood safety research [20]. | |

| Heavy Metals (e.g., Copper) | E. coli O104:H4, Acidovorax citrulli | Induced into VBNC state; resuscitated by chelating agents [19]. | Laboratory studies [19]. | |

| Other Stresses | High Osmolarity/Salinity | E. coli O157:H7 | Induced alongside low temperature and osmotic stress [18]. | Laboratory studies [18]. |

| Oxygen Deprivation | E. coli, Pasteurella piscicida | Induced under low oxygen content [18] [19]. | Laboratory microcosms [18] [19]. |

Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Entry

The transition from a culturable state to a VBNC state is not a passive degradation but an actively regulated process with distinct cellular and molecular hallmarks. The following diagram synthesizes the current understanding of this complex process into a coherent signaling pathway.

Diagram 1: Integrated Signaling Pathway for VBNC Entry. The diagram illustrates how diverse environmental and chemical stressors converge on core cellular damage pathways, triggering a regulated transcriptional response that culminates in the hallmarks of the VBNC state.

Interpretation of the Molecular Pathway

The entry into the VBNC state is a multifaceted response initiated by the perception of stress. As shown in Diagram 1, various stressors lead to fundamental cellular damage, including oxidative stress, macromolecular damage, and envelope stress. A key molecular event is the downregulation of critical repair enzymes, such as methionine sulfoxide reductase, which was identified via transcriptomics in Vibrio vulnificus as being central to the loss of culturability induced by citral [20]. This compromises the cell's ability to repair oxidative damage, locking it into a stress state.

This damage is sensed and transduced into a transcriptional response largely governed by the induction of alternative sigma factors like RpoS (σS) and the activation of two-component systems such as the Cpx pathway [20]. The Cpx system, which responds to envelope stress, is critically involved in reshaping the cell envelope [20]. This coordinated genetic reprogramming drives the phenotypic hallmarks of VBNC entry: a dramatic reduction in metabolic activity, cell dwarfing, extensive modifications to the cytoplasmic membrane fatty acid composition, and increased cross-linking within the peptidoglycan layer [1] [2]. These changes collectively enable survival by minimizing energy expenditure and reinforcing cellular integrity against further environmental insults.

Essential Research Methodologies

Studying the VBNC state requires a combination of classic microbiological techniques and modern molecular biology tools, as the target cells evade standard culture-based detection.

A critical challenge in VBNC research is conclusively demonstrating that colony growth following a stress event results from the resuscitation of non-culturable cells, rather than the mere regrowth of a small number of persistent culturable cells. The following workflow outlines the stringent controls required to confirm true resuscitation.

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow to Confirm VBNC Resuscitation. This multi-step process uses dilution, antibiotics, and scavengers to rule out the regrowth of residual culturable cells.

The validity of the VBNC state hinges on demonstrating resuscitation. Key strategies include:

- Serial Dilution: The induced VBNC-state bacterial suspension is serially diluted to a point where any remaining culturable cells are statistically eliminated [19].

- Antibiotic Treatment: Adding antibiotics like ampicillin to the medium after VBNC induction inhibits the proliferation of any remaining culturable cells, ensuring that subsequent growth is from resuscitated VBNC cells [19].

- H₂O₂ Scavengers: The addition of sodium pyruvate or catalase to the resuscitation medium quenches residual hydrogen peroxide, excluding the possibility that recovery is due solely to the regrowth of H₂O₂-sensitive culturable cells [19].

Detection and Quantification Techniques

Table 2: Key Methods for Detecting and Quantifying VBNC Cells

| Method Category | Specific Technique | Principle | Key Application & Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viability Staining & Microscopy | Direct Viable Count (DVC) | Staining + antibiotic-induced elongation distinguishes viable (elongated) from dead (small) cells [18]. | Initial, microscopy-based method; can be subjective [18]. |

| LIVE/DEAD Staining (e.g., SYTO-9/PI) | Fluorescent dyes distinguish intact (green) vs. damaged (red) membranes [18]. | Must be combined with plate count to distinguish VBNC from culturable live cells [18]. | |

| CTC-DAPI Staining | Measures respiratory activity via tetrazolium salt reduction [18]. | Indicator of metabolic activity in non-culturable cells. | |

| Molecular Methods (Viability-PCR) | PMA-/PMAxx-qPCR | Dye (PMA) penetrates dead cells, binds DNA, and blocks PCR amplification; only viable cells (intact membranes) are quantified [7] [9] [10]. | Gold standard; requires optimization of dye concentration and incubation [9] [10]. Target long gene segments (>500 bp) for higher reliability [7] [21]. |

| PMA-droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) | Same principle as PMA-qPCR, but uses microdroplet partitioning for absolute quantification without a standard curve [9] [10]. | Higher precision and resistance to PCR inhibitors; ideal for complex samples (e.g., feces) [10]. | |

| Activity Assays | Intracellular ATP Measurement | Quantifies ATP levels as a marker of metabolic activity [7]. | Correlates with viability status; VBNC cells maintain moderate ATP levels [7]. |

| Electron Microscopy (SEM/TEM) | Visualizes cell morphology and membrane integrity at high resolution [7] [10]. | Identifies hallmarks like dwarfing and membrane changes [7] [10]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for VBNC Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in VBNC Research | Example Usage & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Propidium Monoazide (PMA) / PMAxx | Viability dye for molecular detection; selectively enters dead cells with compromised membranes and covalently binds DNA upon light exposure, preventing its PCR amplification [7] [9] [10]. | Essential for vPCR (viability PCR) methods like PMA-qPCR and PMA-ddPCR. Concentration (e.g., 5-200 μM) and incubation time (5-30 min) require optimization [9] [10]. |

| Ferrioxamine E | A siderophore that provides the essential micronutrient iron (III); acts as a resuscitation-promoting factor and growth supplement [22]. | Supplementing media (5-200 ng/mL) improves recovery of VBNC cells of Salmonella, Cronobacter spp., and Staphylococcus aureus from food matrices [22]. |

| Chlorine-Based Disinfectants (e.g., NaClO) | A standard chemical stressor for inducing the VBNC state in laboratory settings, mimicking water treatment processes [18] [7]. | Used at concentrations of 0.5-3 mg/L to induce the VBNC state in bacteria like P. aeruginosa; requires quenching with sodium thiosulfate [7]. |

| Specific Gene Primers (Long Amplicon) | Targeting long gene fragments (>500 bp) for PCR detection after PMA treatment increases the likelihood of amplification failure from damaged DNA in dead cells, improving selectivity for viable cells [7] [21]. | e.g., groEL (510 bp) for V. parahaemolyticus; ompW (588 bp) for V. cholerae [21]. |

| Sodium Pyruvate | Acts as a scavenger for reactive oxygen species (ROS) like hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) in culture media [19]. | Critical control in resuscitation experiments; eliminates the confounding effect of H₂O₂-sensitive persister cells that might regrow, ensuring true resuscitation is observed [19]. |

| Artificial Sea Water (ASW) | A defined, nutrient-limited medium used to induce the VBNC state via starvation and/or low-temperature incubation [10]. | Standardized medium for VBNC induction studies, e.g., for Klebsiella pneumoniae and Vibrio species [10]. |

The entry of bacteria into the VBNC state is a finely orchestrated survival response, characterized by specific cellular and molecular hallmarks. Key indicators include a dramatic downscaling of metabolism, morphological reshaping, and a robust molecular response involving sigma factors and two-component systems that rewire gene expression to ensure protection and persistence. Advancements in detection methodologies, particularly viability-PCR techniques, have been instrumental in illuminating this once-elusive state. The experimental frameworks and tools detailed in this guide provide a foundation for continued research. A deeper understanding of the triggers and mechanisms of VBNC entry is not only fundamental to bacterial physiology but also critical for mitigating the significant risks these dormant cells pose to public health, clinical practice, and food safety. Future work should focus on identifying universal molecular markers for VBNC entry and developing targeted strategies to either prevent its induction or safely eliminate VBNC cells.

The viable but nonculturable (VBNC) state is a unique survival strategy adopted by numerous bacteria when confronted with adverse environmental conditions. In this physiological state, cells maintain metabolic activity and viability but cannot form colonies on conventional culture media, the standard method for detecting living bacteria [18]. This dormancy state presents significant challenges for public health, food safety, and clinical medicine, as VBNC pathogens remain potentially pathogenic and can resuscitate when conditions improve [18] [14]. Understanding the molecular mechanisms governing entry into, maintenance within, and resuscitation from the VBNC state is therefore crucial for managing bacterial infections and controlling microbial contamination. Among the complex network of molecular pathways involved, three core triggers have emerged as particularly significant: the stringent response, toxin-antitoxin (TA) systems, and oxidative stress. This review synthesizes current knowledge on these fundamental molecular mechanisms, their interconnectedness, and their roles in the VBNC state, providing researchers with a comprehensive technical guide to these critical processes.

The Stringent Response: A Master Regulator of Bacterial Stress Adaptation

The stringent response is a global bacterial stress adaptation mechanism primarily mediated by the alarmones (p)ppGpp (guanosine tetra- or pentaphosphate). This response is catalyzed by RelA and SpoT enzymes in many bacteria, with RelA primarily synthesizing (p)ppGpp in response to nutrient starvation, particularly uncharged tRNA during amino acid limitation [23]. Under stressful conditions, (p)ppGpp accumulates and triggers a massive reprogramming of cellular physiology, shifting resources from growth-related processes to stress survival pathways.

Molecular Mechanisms and Genetic Regulation

The stringent response functions through several interconnected mechanisms. (p)ppGpp directly binds to RNA polymerase, altering gene expression patterns by favoring the transcription of stress response and virulence genes while repressing growth-related genes for ribosome biogenesis and DNA replication [23]. This regulatory network is further fine-tuned through interactions with other stress response regulators, such as the sigma factor RpoS (σS), which controls the expression of numerous stress resistance genes [23]. The hipAB toxin-antitoxin system also interfaces with the stringent response; HipA phosphorylates glutamate-tRNA ligase, leading to uncharged tRNA accumulation that stimulates (p)ppGpp production via RelA [23].

Role in VBNC State Formation and Maintenance

The stringent response serves as a critical bridge between environmental stress perception and VBNC state induction. Recent research demonstrates that knockout strains with disrupted stringent response pathways, such as ΔrelA E. coli, exhibit diminished growth rates and reduced formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), consequently impairing their ability to develop antibiotic resistance and potentially enter dormancy states [23]. In VBNC Cronobacter sakazakii, both relA and spoT genes are significantly upregulated, indicating that the stringent response regulates antioxidant defense mechanisms, enabling bacterial survival within macrophages by resisting oxidative killing [24]. This enhanced oxidative stress tolerance facilitates pathogen persistence in hostile environments, including within host immune cells.

Table 1: Key Genes in the Stringent Response and Their Roles in the VBNC State

| Gene/Protein | Function | Effect on VBNC State | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| RelA | (p)ppGpp synthase; triggers stringent response | Central regulator; ΔrelA strains show impaired resistance development and reduced ROS [23] | Knockout E. coli ΔrelA had lower growth rates during antibiotic resistance evolution [23] |

| SpoT | Bifunctional: synthesizes and degrades (p)ppGpp | Works with RelA to modulate (p)ppGpp levels | Upregulated in VBNC Cronobacter sakazakii [24] |

| RpoS (σS) | RNA polymerase sigma factor; stress response regulator | Downstream effector of (p)ppGpp; activates stress resistance genes | ΔrpoS knockout showed clear growth rate decrease during kanamycin resistance evolution [23] |

| HipA | Toxin kinase; phosphorylates Glu-tRNA ligase | Induces (p)ppGpp production via RelA by creating uncharged tRNA [23] | Part of the type II toxin-antitoxin system [23] |

Toxin-Antitoxin Systems: Conditional Growth Inhibitors

Type II toxin-antitoxin (TA) systems are genetic modules composed of two elements: a stable toxin protein that inhibits essential cellular processes (e.g., translation, DNA replication) and a labile antitoxin protein or RNA that neutralizes the toxin under normal conditions [25] [26]. These systems are ubiquitously encoded in bacterial chromosomes and have been historically implicated in stress survival, persister cell formation, and biofilm maintenance, though their exact functions remain an active area of research and debate [25].

Diversity and Mechanisms of Action

TA systems are classified based on the nature of the antitoxin and its mechanism of toxin neutralization. Type II systems, the best-characterized class, feature protein antitoxins that directly bind to and inhibit protein toxins [25]. Well-studied examples include:

- RelBE: A ribonuclease toxin that cleaves mRNA; transcription increases following nutritional stress [26].

- MazEF: An endoribonuclease toxin implicated in stress-induced stasis [25].

- CcdAB: The first discovered TA system; originally found on plasmids where it performs post-segregational killing [26].

- VapBC: One of the most common TA families; VapC toxins are ribonucleases [25].

These systems often exhibit conditional cooperativity, where low toxin concentrations enhance antitoxin-binding to DNA promoters, while high concentrations disrupt this binding, providing autoregulatory feedback [26].

Controversial Role in VBNC State

The involvement of TA systems in the VBNC state presents a complex and somewhat controversial picture. While TA systems are frequently postulated to regulate cell growth following stress, and their transcription is strongly induced by diverse stress conditions, recent evidence questions whether this transcriptional induction translates to toxin activation [26].

Multiple studies report substantial increases (often >10-fold) in TA system transcription following stresses like amino acid starvation (induced by serine hydroxamate), translation inhibition (chloramphenicol), oxidative stress (hydrogen peroxide), and DNA damage [26]. However, despite this strong transcriptional response, a strain lacking 10 chromosomal TA systems (Δ10TA) showed no growth disadvantage compared to wild-type E. coli following these stresses, suggesting TA systems are not critical for surviving these individual stresses [26].

The mechanistic explanation for this discrepancy lies in protein stability: although free antitoxin is rapidly degraded during stress, leading to increased TA transcription due to relief of transcriptional autorepression, antitoxin bound to toxin is protected from proteolysis. This protection prevents toxin liberation and activity, meaning transcriptional induction does not necessarily indicate toxin activation [26]. Nonetheless, a study on Salmonella enteritidis found that deletion of the yeaZ gene, which promotes VBNC cell resuscitation, led to upregulation of TA system-related genes, suggesting a potential indirect role in VBNC biology [27].

Table 2: Experimental Responses of Type II TA Systems to Stress Conditions

| Stress Condition | Inducing Agent | Example TA System Response | Evidence of Toxin Activation? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amino Acid Starvation | Serine Hydroxamate (SHX) | >6-fold increase in mqsRA, relBE, yefM-yoeB mRNA [26] | No; Δ10TA strain showed no growth defect [26] |

| Translation Inhibition | Chloramphenicol | >6-fold increase in mqsRA, relBE, yefM-yoeB mRNA [26] | No; Δ10TA strain showed no growth defect [26] |

| Oxidative Stress | Hydrogen Peroxide | Transcriptional induction of multiple TA systems [26] | No evidence from RNA sequencing [26] |

| DNA Synthesis Inhibition | Trimethoprim | Transcriptional induction of multiple TA systems [26] | Not detected [26] |

| Heat Shock | Temperature shift (30°C to 45°C) | Substantial increases in TA transcription [26] | Not detected [26] |

Oxidative Stress: A Common Inducer of Bacterial Dormancy

Oxidative stress occurs when bacteria encounter an imbalance between reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and their detoxification, leading to accumulation of damaging molecules like superoxide anions (O₂⁻), hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), and hydroxyl radicals (OH•). This stressor is particularly relevant as it is both a common environmental challenge and a key weapon used by host immune systems to kill pathogens.

Bacteria face oxidative stress from multiple sources:

- Environmental exposures: UV radiation, hydrogen peroxide, and other oxidizing agents [18] [28].

- Metabolic byproducts: Endogenous ROS production from electron transport during respiration [23].

- Host immune response: Phagocytes like macrophages generate an oxidative burst to kill internalized bacteria [24].

- Antibiotic exposure: Bactericidal antibiotics can induce ROS formation as part of their killing mechanism [23].

To combat oxidative damage, bacteria employ sophisticated defense systems including superoxide dismutases (SodA, SodB) that convert O₂⁻ to H₂O₂, catalases (KatG) that break down H₂O₂ to water and oxygen, and thioredoxin (TrxA) systems that repair oxidative damage [23] [24].

Oxidative Stress and VBNC State Interconnections

Oxidative stress serves as a direct trigger for VBNC state entry while also interacting with other molecular pathways. Sublethal ROS levels can cause DNA damage that activates stress responses and increases mutation rates, potentially accelerating resistance development [23]. UV disinfection, which induces oxidative damage, can trigger E. coli to enter the VBNC state at doses as low as 4.5 mJ/cm², with the DNA damage repair protein RecA playing a key role in this process [28].

Once in the VBNC state, bacteria exhibit enhanced resistance to oxidative stress. VBNC Cronobacter sakazakii demonstrates higher survival rates under oxidative conditions compared to culturable cells, with corresponding upregulation of antioxidant genes (sodA, katG, trxA) and stringent response genes (relA, spoT) [24]. This suggests that VBNC cells activate a coordinated defense program, potentially regulated by the stringent response, to survive within hostile environments like macrophages.

Table 3: Key Oxidative Stress Defense Components and Their Roles in VBNC Cells

| Gene/Protein | Function in Oxidative Stress Defense | Role in VBNC State |

|---|---|---|

| SodA, SodB | Superoxide dismutase; destroys superoxide anion radicals [23] | Upregulated in VBNC Cronobacter sakazakii; essential for survival in macrophages [24] |

| KatG | Catalase-peroxidase; breaks down hydrogen peroxide [24] | Upregulated in VBNC Cronobacter sakazakii [24] |

| TrxA | Thioredoxin; involved in redox homeostasis and damage repair [24] | Upregulated in VBNC Cronobacter sakazakii [24] |

| SoxR, SoxS | Transcriptional regulators of superoxide response [23] | Knockout strains (ΔsoxR, ΔsoxS) showed faster growth rate decreases during resistance evolution [23] |

| RecA | DNA repair protein; responds to oxidative DNA damage [28] | Expression indicates recovery capacity in UV-induced VBNC E. coli [28] |

Integrated Molecular Pathways and Technical Approaches

The three core molecular triggers do not function in isolation but rather form an integrated network that regulates entry into and maintenance of the VBNC state. Understanding these interconnected pathways and the methods to study them is essential for researchers investigating bacterial dormancy.

Pathway Interconnections

The stringent response, TA systems, and oxidative stress pathways intersect at multiple regulatory points. The stringent response alarmone (p)ppGpp can stimulate ROS formation, creating a potential link between nutrient stress and oxidative damage [23]. Additionally, the stringent response regulates antioxidant defense mechanisms in VBNC cells, as demonstrated by the coordinated upregulation of relA/spoT and antioxidant genes in VBNC Cronobacter sakazakii [24]. While TA systems may not be directly activated by stress, their transcription is influenced by these master regulators, and they may play supporting roles in the overall stress response network.

Diagram 1: Integrated Molecular Pathways to VBNC State. This diagram illustrates the interconnected network of environmental stresses and cellular responses that lead to VBNC state formation, highlighting both well-established connections (solid lines) and debated/weaker evidence (dashed lines).

Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Studying the VBNC state and its molecular triggers requires specialized approaches that combine classical microbiology with modern molecular techniques. The following toolkit represents essential reagents and methodologies used in this field.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Investigating VBNC Molecular Triggers

| Category | Specific Reagents/Methods | Application/Function | Example Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| VBNC Induction | Ampicillin (400 µg/mL in saline) [24], UV light (4.5 mJ/cm²) [28], Low temperature + osmotic stress [15] | Induce VBNC state under controlled conditions | Inducing VBNC in Cronobacter sakazakii [24] and E. coli [28] |

| Viability Staining | LIVE/DEAD BacLight fluorescent stain (SYTO-9/PI) [18] [29], CTC-DAPI staining [18] | Distinguish live/dead cells based on membrane integrity and metabolic activity | Monitoring P. syringae viability after acetosyringone treatment [29] |

| Molecular Detection | PMAxx-qPCR [24], RT-PCR for virulence genes (ipaH, ipaD) [15], RNA sequencing [29] | Detect and quantify VBNC cells; measure gene expression | Detecting VBNC Salmonella [15] and gene expression in VBNC P. syringae [29] |

| Mutant Construction | Lambda Red homologous recombination [27], Single-gene knockouts (ΔrelA, ΔsodA, etc.) [23] | Create specific gene deletions to study function | Constructing ΔyeaZ Salmonella mutant [27] |

| Stress Application | Serine hydroxamate (SHX) [26], Hydrogen peroxide [26] [24], Chloramphenicol [26] | Induce specific stress responses (stringent, oxidative, translation inhibition) | Studying TA system transcription after stress [26] |

Experimental Workflow for VBNC Research

A systematic approach is essential for rigorously investigating the molecular triggers of the VBNC state. The following workflow, visualized in Diagram 2, outlines key methodological stages from strain preparation through data interpretation.

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for VBNC Research. This diagram outlines a systematic approach for investigating molecular triggers of the VBNC state, from initial strain preparation through functional validation and resuscitation studies. Dashed lines represent potential iterative research cycles.

The stringent response, toxin-antitoxin systems, and oxidative stress represent three core molecular triggers that collectively regulate entry into and maintenance of the VBNC state. While the stringent response and oxidative stress demonstrate well-established roles in this dormancy state, with clear evidence of their activation and contribution to stress adaptation and survival, the involvement of TA systems appears more nuanced, with strong transcriptional induction but limited evidence of toxin activation during stress. The interconnectedness of these pathways creates a robust network that allows bacteria to sense environmental threats and implement survival strategies, including transition to the VBNC state.

Significant challenges remain in fully elucidating these mechanisms, particularly in distinguishing between correlation and causation in pathway activation, understanding the precise sequence of molecular events during VBNC induction, and developing strategies to prevent VBNC formation or eradicate VBNC cells. Future research should focus on temporal analyses of pathway activation, single-cell studies to address population heterogeneity, and interventional approaches targeting these core pathways to control VBNC bacteria. As our understanding of these fundamental molecular mechanisms deepens, so too will our ability to combat the significant public health challenges posed by VBNC pathogens in clinical, food safety, and environmental contexts.

Distinguishing VBNC from Persister Cells and True Cell Death

Within the realm of bacterial stress response and survival, the viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state and persister cells represent two critical dormant phenotypes that confound traditional microbiological detection and clinical treatment. Both states allow bacteria to withstand lethal environmental insults and antibiotic challenges, yet they are fundamentally distinct in their physiological characteristics and clinical implications. The accurate differentiation between VBNC cells, persister cells, and truly dead cells is not merely academic—it represents a pressing challenge in clinical microbiology, pharmaceutical development, and public health. Failure to distinguish these states can lead to misinterpretation of treatment efficacy, unexplained disease recurrence, and underestimation of bacterial contamination risks. This guide provides a comprehensive technical framework for researchers and drug development professionals to correctly identify and characterize these distinct cellular states within the broader context of bacterial VBNC research.

Defining the States: Theoretical Framework and Key Characteristics

Conceptual Definitions and Distinctions

The Viable But Non-Culturable (VBNC) state is a survival strategy wherein bacteria, in response to environmental stress, lose the ability to form colonies on conventional growth media that would normally support their proliferation, while maintaining viability and metabolic activity [4]. These cells are not dead; they retain an intact cell membrane, demonstrate low-level metabolic activity, continue gene expression, and possess the potential to resuscitate under appropriate conditions [30] [31]. The VBNC state is now recognized as a major public health concern because these cells evade standard culture-based detection methods yet remain capable of causing infections.

Persister cells represent a small subpopulation of dormant, non-growing cells within an otherwise susceptible bacterial population that exhibit extreme tolerance to high-dose antibiotic treatment without undergoing genetic resistance mutations [30] [32]. Unlike VBNC cells, persisters remain culturable—they can resume growth on standard media shortly after the removal of the antibiotic stress [30] [4]. Their formation can be stochastic or induced by environmental cues, and they are increasingly implicated in recurrent and chronic bacterial infections.

True Cell Death represents the irreversible loss of bacterial viability, characterized by complete and permanent cessation of all metabolic functions and irreversible damage to cellular integrity, particularly the cell membrane [8] [4].

The Dormancy Continuum Hypothesis

Emerging evidence suggests that VBNC cells and persisters may not represent completely separate phenomena but rather exist along a dormancy continuum [30]. This model proposes that active cells under stress can transition into persisters, which may subsequently develop into VBNC cells in response to prolonged or intensified stress [30] [14]. Supporting this hypothesis, research on Vibrio vulnificus demonstrated that persister cells isolated through antibiotic treatment transitioned into the VBNC state more rapidly (4-5 days) compared to log-phase cells (7-10 days), suggesting that persisters are primed for deeper dormancy [30] [14].

The following diagram illustrates this theoretical relationship and the key differentiating features along the dormancy spectrum:

Comparative Analysis: Key Differentiating Parameters

The accurate discrimination between VBNC cells, persister cells, and dead cells requires assessment across multiple cellular parameters. The table below summarizes the defining characteristics of each state:

Table 1: Key Differentiating Features of VBNC Cells, Persister Cells, and True Cell Death

| Parameter | VBNC Cells | Persister Cells | True Cell Death |

|---|---|---|---|

| Culturability on Standard Media | Lost (CFU = 0) [4] | Retained (able to form colonies after stress removal) [30] [4] | Lost (irreversible) |

| Metabolic Activity | Low but measurable; maintains membrane potential & ATP [4] | Greatly reduced but detectable [32] | Absent (irreversible loss) |

| Membrane Integrity | Intact [8] [4] | Intact [30] | Compromised/damaged [8] |

| Gene Expression/Translation | Active (continuous but reduced) [31] [4] | Active but altered [30] | Absent |

| Induction Triggers | Moderate, long-term stresses: starvation, extreme T°, salinity, chlorine, food preservatives [31] [4] [17] | Specific, often antibiotic-mediated stress [4] [32] | Lethal insults (extreme heat, high doses of disinfectants) |

| Resuscitation | Requires specific stimuli (e.g., temperature upshift, nutrient addition, Rpf); conditions differ from original culture [30] [4] | Rapid upon removal of inducing stress (e.g., antibiotic removal) [30] [4] | Not possible |

| Antibiotic Tolerance | High (due to low metabolic activity) [30] [33] | High tolerance (antibiotic-specific) [30] [32] | N/A |

| Detection Methods | Viability qPCR (PMA/EMA-qPCR), Live/Dead staining combined with culturability assessment [8] [4] [34] | Culture after antibiotic removal & washing [30] | Standard plate count (no growth), permeability to viability dyes [8] |

Beyond the fundamental differences outlined above, several additional distinctions are critical for researchers:

Virulence Potential: VBNC cells often retain pathogenicity. Pathogenic E. coli O157 and Campylobacter jejuni in the VBNC state have been linked to food poisoning incidents, and VBNC cells can resuscitate in vivo to regain full infectivity [30] [34]. Persister cells, while tolerant to antibiotics, do not necessarily exhibit altered virulence upon resuscitation.

Molecular Mechanisms: Toxin-antitoxin (TAS) systems are classically implicated in persister formation but have also been shown to play a role in VBNC induction, particularly in response to human serum, suggesting overlapping but distinct regulatory pathways [30].

Methodological Guide: Detection and Differentiation Protocols

Core Experimental Workflow

A robust approach to differentiating these states requires a combination of cultural and molecular methods. The following workflow provides a systematic protocol for characterization:

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Isolating and Confirming Persister Cells

This protocol is adapted from studies on Vibrio vulnificus and E. coli [30]:

- Culture Preparation: Grow the bacterial strain to log phase (OD₆₁₀ ~0.15-0.25) in appropriate broth (e.g., Heart Infusion broth).

- Antibiotic Treatment: Expose the culture to a high concentration of a bactericidal antibiotic (e.g., 100 µg/mL ampicillin) for 4 hours at the optimal growth temperature with aeration.

- Wash and Remove Antibiotic: Centrifuge the antibiotic-treated culture and wash the pellet four times with a buffer (e.g., PBS, 1/2 Artificial Seawater for vibrios, or 0.85% NaCl for E. coli) to thoroughly remove the antibiotic.

- Assess Culturability: Perform serial dilutions of the washed cell suspension and plate on appropriate non-selective solid media (e.g., HI agar). Incubate under optimal conditions and enumerate colony-forming units (CFU/mL).

- Interpretation: The surviving cells that regrow on the plates after this process are defined as persister cells. Their culturability returns rapidly (within the standard incubation time of the organism) once the antibiotic is removed [30] [4].

Protocol for Inducing and Confirming the VBNC State

This protocol uses nutrient starvation at low temperature, a common VBNC-inducing condition [30]:

- Induction: Take a log-phase culture, wash twice with a nutrient-free buffer (e.g., 1/2 Artificial Seawater for marine vibrios) to remove nutrients. Dilute 1:100 in the same buffer and incubate statically at 4°C.

- Monitor Culturability: Quantify culturable cells daily by plate counts. The population is considered to have entered the VBNC state when culturable counts drop below the detection limit (<10 CFU/mL) on standard media that normally supports growth [30].

- Assess Viability of Non-Culturable Cells: Use a viability assay to confirm the cells are not dead.

- BacLight Live/Dead Kit: Stain cells with SYTO 9 (green, penetrates all cells) and propidium iodide (red, penetrates only membrane-compromised cells). Viable cells with intact membranes will fluoresce green. Count green-fluorescent cells using epifluorescence microscopy or flow cytometry [30].

- Viability qPCR (v-qPCR): Treat samples with propidium monoazide (PMA) or PMAxx, which penetrates only dead cells with compromised membranes and binds to DNA, inhibiting its amplification in PCR. After light exposure and DNA extraction, perform qPCR. The signal corresponds to DNA from viable (including VBNC) cells with intact membranes [8] [34].

- Resuscitation Test: To confirm the VBNC state, attempt to resuscitate the non-culturable population. Incubate the VBNC-inducing culture at a permissive temperature (e.g., 20°C for 24 hours) without adding rich nutrients. After this incubation, re-plate on standard media. An increase in CFU indicates resuscitation from the VBNC state [30]. A key differentiator is that resuscitation of VBNC cells often requires specific conditions different from their original growth conditions, unlike persisters [4].

Protocol for Viability qPCR (v-qPCR) to Detect VBNC Cells

This method is crucial for detecting and quantifying VBNC cells in complex matrices [8] [34] [17]:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare bacterial samples containing a mixture of live, dead, and potentially VBNC cells.

- Dye Treatment: Add a combination of EMA (10 µM) and PMAxx (75 µM) to the sample. EMA penetrates cells with slightly damaged membranes and is effluxed by active cells, while PMAxx is excluded from cells with intact membranes. Incubate the sample in the dark at 40°C for 40 minutes with occasional mixing.

- Photoactivation: Expose the tube to a bright halogen light source (e.g., 500-W halogen lamp at 20 cm distance) for 15 minutes to crosslink the dyes to DNA from dead cells.

- DNA Extraction: Wash the cells to remove residual dye and extract genomic DNA using a commercial kit.

- qPCR Analysis: Perform quantitative PCR using species-specific primers (e.g., targeting rpoB for C. jejuni [34]). The resulting qPCR signal will predominantly originate from viable cells (including VBNC), as the DNA from dead cells is covalently modified and cannot be amplified.

- Quantification: The number of VBNC cells can be estimated by subtracting the number of culturable cells (from plate counts) from the total viable cell count obtained via v-qPCR [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Studying Dormant Bacterial States

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Propidium Monoazide (PMA)/PMAxx | Viability dye for v-qPCR; enters dead cells with compromised membranes, binding DNA and inhibiting PCR amplification [8] [34]. | Used in v-qPCR to differentiate viable VBNC cells (PMA-negative) from dead cells (PMA-positive) in Listeria monocytogenes and Campylobacter jejuni [8] [34] [17]. |

| Ethidium Monoazide (EMA) | Viability dye often used in combination with PMA for v-qPCR; can penetrate slightly damaged membranes [8] [17]. | A combination of EMA (10 µM) and PMAxx (75 µM) was optimal for detecting VBNC L. monocytogenes in process wash water [8] [17]. |

| BacLight Live/Dead Viability Kit | Fluorescent staining for microscopy/flow cytometry; SYTO9 stains all cells, PI stains only dead cells with damaged membranes [30] [8]. | Used to confirm membrane integrity of Vibrio vulnificus VBNC cells by flow cytometry; viable cells fluoresce green [30]. |

| Resuscitation-Promoting Factor (Rpf) | Bacterial cytokine that stimulates the resuscitation of VBNC cells [35]. | Identified in Micrococcus luteus and other Actinobacteria; can be used to resuscitate VBNC cells in bioremediation studies [35]. |

| Toxin-Antitoxin System Mutants | Genetic tools to study molecular mechanisms of dormancy [30]. | Used in E. coli and V. vulnificus to demonstrate the role of TAS in the formation of both persister and VBNC cells [30]. |

| Artificial Seawater (ASW)/Saline | Nutrient-free buffer for inducing VBNC state in aquatic bacteria [30]. | Used to induce the VBNC state in V. vulnificus via nutrient starvation at low temperatures [30]. |

| Chlorine-based Sanitizers | Chemical stressor to induce VBNC state in foodborne pathogens [17]. | Sodium hypochlorite (10 mg/L free chlorine) induces VBNC state in L. monocytogenes and Salmonella enterica in produce wash water [17]. |

The precise differentiation between VBNC cells, persister cells, and true cellular death is a cornerstone of advanced microbiological research with profound implications for clinical diagnostics, therapeutic development, and public health microbiology. While both VBNC and persister cells represent dormant, stress-tolerant phenotypes, they are defined by critical differences in culturability and resuscitation requirements. Persisters remain culturable on standard media upon stress removal, whereas VBNC cells lose this ability and require specific resuscitation signals. The emerging "dormancy continuum" model provides a valuable theoretical framework, suggesting these states may be interconnected points on a spectrum of microbial dormancy.

Moving forward, researchers must employ a multi-faceted approach, combining traditional culturability assays with modern molecular techniques like viability qPCR and advanced staining methods. Standardizing these protocols across laboratories will be essential for generating comparable data and driving the field toward a unified understanding of these elusive bacterial states. Furthermore, the development of novel therapeutic agents that either prevent entry into dormancy or effectively eradicate dormant cells represents one of the most promising yet challenging frontiers in combating persistent and recurrent bacterial infections.

Beyond the Plate: Advanced Methodologies for Detecting and Quantifying VBNC Cells

Limitations of Conventional Culture and the Need for Viability Testing

For over a century, the gold standard for detecting and quantifying viable bacteria has been their ability to form visible colonies on nutrient media. However, this conventional culture approach fundamentally underestimates true microbial viability. The "great plate count anomaly" describes the phenomenon where microscopic counts of viable cells far exceed the numbers capable of growing on standard culture media [36]. A key explanation for this discrepancy is the viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state, a dormant survival strategy adopted by numerous bacterial species in response to environmental stress [5] [37]. In the VBNC state, bacteria fail to grow on routine media but maintain metabolic activity, membrane integrity, and potential pathogenicity, presenting a formidable challenge to public health, food safety, and pharmaceutical sterility testing [37] [38]. This whitepaper details the limitations of traditional culture methods, explores the VBNC state's characteristics, and advocates for the adoption of advanced viability testing to mitigate the risks posed by these undetectable pathogens.

The Viable But Non-Culturable State: A Survival Strategy

Defining the VBNC State

The VBNC state is a unique physiological condition induced by various environmental stresses. Cells in this state are characterized by a loss of culturability on standard media that normally support their growth, while they retain viability markers such as an intact membrane, metabolic activity, and genetic potential for resuscitation [4]. First identified in 1982 in Escherichia coli and Vibrio cholerae [5], the list of bacteria known to enter the VBNC state has grown to encompass over 100 species, including significant human pathogens such as E. coli O157:H7, Salmonella enterica, Listeria monocytogenes, and Campylobacter jejuni [5] [3] [38].

Key Characteristics and Differences from Other States

It is crucial to differentiate VBNC cells from both culturable cells and dead cells. The table below summarizes the defining characteristics.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Different Bacterial Physiological States

| Feature | Culturable Cells | VBNC Cells | Dead Cells |

|---|---|---|---|

| Culturability | Forms colonies on standard media | Cannot form colonies on standard media | Cannot form colonies on any media |

| Metabolic Activity | High | Low but measurable [37] | Absent |

| Membrane Integrity | Intact | Intact [37] | Damaged |

| Genetic Material | Intact | Intact and retained [37] | Degraded |

| Gene Expression | Active | Continued transcription & translation [37] [3] | Absent |

| Respiratory Activity | Present | Present [37] | Absent |

| Potential for Resuscitation | Not applicable | Yes, under specific conditions | No |

VBNC cells also differ from persister cells, another dormant subpopulation. While both are tolerant to antibiotics, persister cells remain culturable once the antibiotic is removed, whereas VBNC cells are non-culturable and require specific resuscitation signals to regain culturability [37] [4].

Limitations of Conventional Culture-Based Methods

Reliance on plate counting and other growth-based assays for viability assessment presents several critical limitations:

- Inability to Detect VBNC Pathogens: This is the most significant drawback. Conventional methods yield false negatives when pathogens enter the VBNC state, creating a dangerous blind spot in safety monitoring [5] [38]. For instance, E. coli O157:H7 can enter the VBNC state on lettuce and spinach, evading detection before consumption [5].

- Underestimation of Microbial Load and Risk: The failure to detect VBNC cells leads to a significant underestimation of the total viable bacterial population in clinical, environmental, and product samples, resulting in a false sense of security [39].

- Inability to Inform on True Metabolic State: Culture methods confirm only the ability to replicate under specific conditions. They provide no direct information on the metabolic state, membrane integrity, or virulence potential of cells that do not form colonies [37].

- Link to Unexplained Disease Outbreaks: The VBNC state is suspected to be a factor in foodborne outbreaks where routine testing fails to identify a causative agent. For example, VBNC Salmonella Oranienburg was linked to an outbreak from dried squid, and VBNC E. coli O157 was implicated in an outbreak from salted salmon roe [5].

Conditions Inducing the VBNC State and Associated Risks

A wide array of common stresses can induce the VBNC state, many of which are standard practices in food processing, water treatment, and pharmaceutical manufacturing.

Table 2: Common Inducers of the VBNC State in Foodborne and Waterborne Pathogens

| Inducing Condition | Example Pathogens | Relevant Context |

|---|---|---|

| Low Temperature | Listeria monocytogenes, E. coli O157:H7 [5] | Refrigerated food storage |

| Nutrient Starvation | Vibrio cholerae, Campylobacter jejuni [5] [37] | Water systems, low-nutrient foods |

| High Osmolarity/Salinity | Salmonella Oranienburg [5] | Salted foods, cheese |

| Oxidative Stress | Campylobacter jejuni [38] | Exposure to disinfectants |

| Low pH | Listeria monocytogenes [5] | Acidic foods, beverages |

| Chlorination | Various waterborne pathogens [5] [3] | Water treatment |

| UV Light/Irradiation | E. coli O157:H7 [5] [38] | Food and surface sterilization |

| High Pressure | Listeria monocytogenes, Bacillus cereus [5] | Food pasteurization (e.g., HPP) |

| Preservatives | Potassium sorbate, sodium benzoate [5] [3] | Processed foods, cosmetics |

| Household Cleaners | L. monocytogenes, S. aureus, E. coli [39] | Sanitation protocols |

The major risk associated with VBNC cells is their potential for resuscitation. When the inducing stress is removed or conditions become favorable, VBNC cells can resuscitate and resume full metabolic activity and virulence. Resuscitation can occur in food products [38], water systems, or inside a human host, potentially leading to disease outbreaks long after a product was deemed "safe" by conventional testing [5] [40]. Furthermore, some VBNC pathogens, such as certain strains of E. coli, retain the ability to produce toxins while in the non-culturable state, posing a direct health threat even without resuscitation [39] [40].

Advanced Viability Testing Methodologies

To overcome the limitations of culture-based methods, a suite of growth-independent techniques is required. The following workflow outlines a comprehensive strategy for detecting VBNC cells.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Propidium Monoazide (PMA) coupled with qPCR

This method selectively detects cells with intact membranes, a key characteristic of VBNC cells [4].

- Sample Preparation: Suspend bacterial cells in PBS.

- PMA Treatment: Add PMA dye to the sample to a final concentration of 50-100 µM. Incubate in the dark for 5-10 minutes.

- Photoactivation: Expose the sample to bright light (e.g., a 500-W halogen lamp) for 15-20 minutes. PMA crosses compromised membranes of dead cells and intercalates into DNA, forming a covalent crosslink upon light exposure. This crosslink inhibits PCR amplification. In viable/VBNC cells with intact membranes, PMA cannot enter and thus DNA remains amplifiable.

- DNA Extraction: Proceed with standard genomic DNA extraction.

- qPCR Amplification: Perform qPCR targeting a species-specific gene. A positive signal indicates the presence of viable/VBNC cells with intact membranes.

Direct Viable Count (DVC) and Fluorescence Microscopy

This method identifies cells that are metabolically active and capable of elongation [37].

- Sample Incubation: Incubate the sample in a nutrient broth (e.g., yeast extract broth) containing nalidixic acid (0.002%) and yeast extract. Nalidixic acid inhibits DNA division without affecting RNA or protein synthesis.

- Incubation Conditions: Incubate for 6-8 hours at an appropriate growth temperature.

- Staining: Filter the sample and stain with a fluorescent dye such as acridine orange.

- Enumeration: Examine under an epifluorescence microscope. Metabolically active VBNC cells will appear as elongated, fluorescent filaments due to continued growth without division. Compare counts to those from a control without nalidixic acid.

Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP) Bioluminescence Assay

This assay measures metabolic activity by detecting ATP, present in all living cells [39].

- Cell Lysis: Lyse bacterial cells to release intracellular ATP.

- Reaction: Mix the lysate with a luciferin-luciferase enzyme substrate.

- Detection: Measure the resulting bioluminescent light output with a luminometer. The light intensity is directly proportional to the ATP concentration, which correlates with the number of viable/VBNC cells.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Kits for VBNC Research

| Reagent/Kits | Function | Key Application in VBNC Research |

|---|---|---|

| PMA/Dye Treatment Kits (e.g., PMAxx, EMA) | Selective DNA modification of dead cells | Differentiating VBNC (PMA-negative) from dead (PMA-positive) cells in PCR assays [4] |

| LIVE/DEAD BacLight Bacterial Viability Kits | Dual fluorescent staining of cells | Simultaneously visualizing cells with intact (green) and damaged (red) membranes via microscopy [39] |

| ATP Bioluminescence Assay Kits | Quantification of cellular ATP | Rapidly measuring metabolic activity as a marker of viability in VBNC cells [39] |

| Bacterial RNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality RNA | Detecting gene expression (mRNA) in metabolically active VBNC cells via RT-qPCR [37] [40] |

| Resuscitation-Promoting Factor (Rpf) | Bacterial cytokine | Stimulating the resuscitation of VBNC cells in specific Gram-positive bacteria for experimental confirmation [40] |

| CTC (5-Cyano-2,3-Ditolyl Tetrazolium Chloride) | Tetrazolium dye | Detecting respiratory activity in VBNC cells by measuring electron transport system activity [37] |