Traditional vs. Molecular AST Methods: A Comprehensive Guide for Research and Diagnostic Applications

This article provides a comparative analysis of traditional phenotypic and modern molecular Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST) methods for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Traditional vs. Molecular AST Methods: A Comprehensive Guide for Research and Diagnostic Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comparative analysis of traditional phenotypic and modern molecular Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST) methods for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of established techniques like disk diffusion and broth microdilution, alongside emerging methods such as next-generation sequencing, microfluidics, and automated platforms. The content details practical applications, troubleshooting for common implementation barriers, and frameworks for clinical validation. By synthesizing current evidence and future trends, this guide aims to inform strategic decisions in AST methodology for both clinical diagnostics and antimicrobial drug development.

The Bedrock of AST: Understanding Traditional Phenotypic Methods and the Molecular Revolution

Core Principles of Conventional Phenotypic AST

Conventional phenotypic antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) represents a cornerstone of clinical microbiology, providing an empirical measure of a pathogen's response to antimicrobial agents in vitro. These methods directly observe the effect of antibiotics on bacterial growth, offering a functional profile of susceptibility or resistance that guides therapeutic decisions [1] [2]. Despite the emergence of molecular techniques, conventional phenotypic methods remain the gold standard against which new technologies are validated, forming an indispensable component of both routine clinical practice and antimicrobial resistance research [1] [3]. The fundamental principle underpinning these methods is the determination of the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC)—the lowest concentration of an antimicrobial agent that prevents visible growth of a microorganism [2]. This quantitative measurement serves as the basis for categorizing isolates as susceptible (S), intermediate (I), or resistant (R) according to established breakpoints from standards organizations such as the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) and the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) [1].

The continued relevance of conventional phenotypic AST in an era of advancing technology stems from its ability to detect resistance regardless of genetic mechanism, including previously unidentified resistance patterns [1]. This comprehensive phenotypic profiling is crucial for effective antimicrobial stewardship, surveillance of emerging resistance trends, and validation of genotypic resistance detection methods [2]. This guide examines the core principles, methodologies, and performance characteristics of conventional phenotypic AST systems, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a foundation for evaluating their application in both clinical and research contexts.

Fundamental Methodologies and Principles

Conventional phenotypic AST encompasses several well-established techniques, each with distinct procedural approaches but shared fundamental principles. The three primary methods—disk diffusion, broth dilution, and agar dilution—all rely on measuring the interaction between antimicrobial agents and bacterial cells under standardized conditions to generate reproducible susceptibility profiles [1] [2].

Disk Diffusion Method

The disk diffusion method, also known as the Kirby-Bauer test, is one of the most widely used phenotypic AST techniques due to its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and flexibility [1]. The methodology involves applying a standardized inoculum of the test microorganism to the surface of an agar plate, followed by placement of paper disks impregnated with specific concentrations of antimicrobial agents [1] [2]. After overnight incubation (typically 16-24 hours), the diameter of the zone of inhibition around each disk is measured in millimeters. This zone size correlates inversely with the MIC and is interpreted using established breakpoint tables to categorize the organism as susceptible, intermediate, or resistant to each antimicrobial agent [1].

Key advantages of disk diffusion include its ability to test multiple antibiotics simultaneously on a single plate, minimal equipment requirements, and cost efficiency for low-volume laboratories [1]. However, the method only provides qualitative or semi-quantitative results (categorical interpretations rather than precise MIC values) and requires strict adherence to standardized protocols for reliable results [1] [2].

Broth Dilution Methods

Broth dilution methods provide quantitative MIC values through a series of antimicrobial concentrations prepared in liquid growth media [2]. In macrobroth dilution, antibiotics are serially diluted in test tubes containing a standardized bacterial inoculum [1]. After incubation, the lowest concentration showing no visible growth is identified as the MIC. Microbroth dilution adapts this principle to microtiter plates, enabling high-throughput testing of multiple organism-antibiotic combinations simultaneously [1] [2]. The miniaturized format reduces reagent consumption and labor while maintaining accuracy, making it suitable for both clinical and research applications [2].

Broth dilution methods are particularly valuable for determining precise MIC values needed for treatment individualization, research studies, and establishing epidemiological cut-off values [1]. The methodology forms the basis for many automated AST systems and serves as the reference method for validating other AST techniques according to international standards [2].

Agar Dilution Method

The agar dilution method incorporates antimicrobial agents directly into the agar medium at predetermined doubling dilutions [2]. A standardized inoculum of test organisms is applied to the antibiotic-containing plates, typically using multi-point inoculators that enable efficient testing of multiple isolates against a single antibiotic concentration [1]. After incubation, the MIC is defined as the lowest antibiotic concentration that completely inhibits visible growth, with a faint haze or single colony being disregarded [2].

This method offers excellent reproducibility and is particularly efficient for testing large numbers of bacterial isolates against a limited panel of antibiotics [1]. It remains the recommended method for AST of fastidious organisms such as Helicobacter pylori and anaerobic bacteria, for which broth-based methods may not provide reliable results [2]. However, agar dilution is labor-intensive for testing single isolates against multiple antibiotics and requires preparation of numerous plates, making it less suitable for routine testing of individual clinical isolates [1].

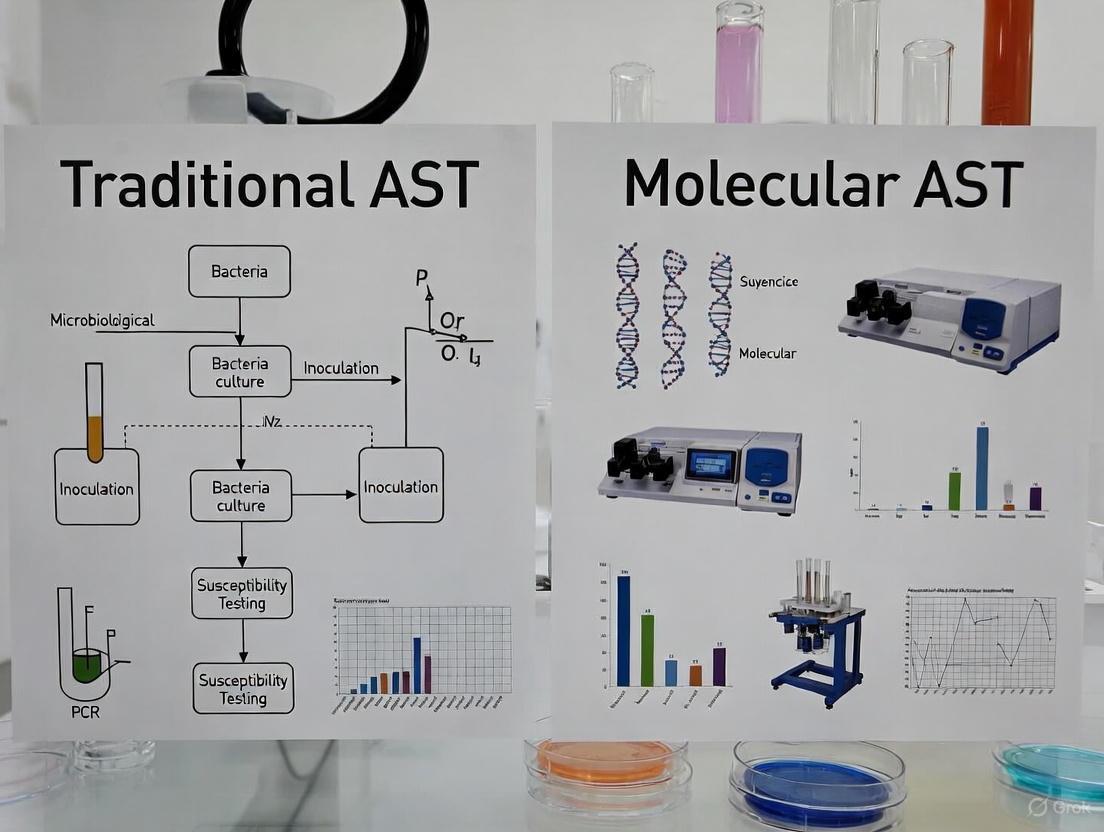

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow common to these conventional phenotypic AST methods:

Performance Comparison of Conventional and Automated Phenotypic AST Systems

While manual methods remain in widespread use, automated systems have significantly improved the efficiency of phenotypic AST in clinical laboratories. The following table compares the performance characteristics of conventional methods with representative automated and rapid phenotypic systems:

Table 1: Performance comparison of antimicrobial susceptibility testing methods

| Method | Time to Result | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disk Diffusion [1] | 16-24 hours after isolation | Cost-effective, flexible, multiple drugs per plate | Qualitative/semi-quantitative only, labor-intensive | Routine clinical testing, epidemiological studies |

| Broth Microdilution [1] [2] | 16-24 hours after isolation | Quantitative MIC, reference method, suitable for fastidious organisms | Labor-intensive, requires precise preparation | Reference testing, research, fastidious organisms |

| Agar Dilution [1] [2] | 16-24 hours after isolation | Efficient for multiple isolates, excellent reproducibility | Not efficient for single isolates, labor-intensive | Large-scale screening, fastidious organisms |

| Selux DX System [4] | Average 5.5 hours after isolation | Rapid, automated, quantitative MIC | Longer setup time, higher cost | Rapid clinical testing, stewardship programs |

| LifeScale System [5] | 4-6 hours directly from positive blood culture | Direct from blood culture, measures bacterial mass | Limited database, primarily Gram-negative rods | Rapid bacteremia testing, critical care settings |

Recent evaluations of rapid phenotypic systems demonstrate significant advances in testing speed while maintaining acceptable performance compared to reference methods. A 2025 study of the Selux DX system reported ≥90% categorical agreement for most drug-organism combinations with an average turnaround time of 5.5 hours—substantially faster than conventional methods requiring 16-24 hours [4]. Similarly, the LifeScale system achieved AST results directly from positive blood cultures in less than 5 hours by utilizing microfluidic sensors with mechanical resonators that measure the mass of individual microbes [5].

Despite these advances, conventional methods maintain certain advantages, particularly for specialized applications. Disk diffusion remains unsurpassed for testing novel antimicrobial agents not yet incorporated into commercial panels, while broth and agar dilution provide definitive MIC values essential for establishing interpretive criteria and validating new methods [1] [2]. The choice of methodology therefore depends on the specific application, required turnaround time, available resources, and intended use of the results.

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Details

Standardized Disk Diffusion Protocol

The reliability of conventional phenotypic AST depends on strict adherence to standardized methodologies. The following protocol for disk diffusion testing follows CLSI and EUCAST guidelines [1]:

Inoculum Preparation: Select 3-5 well-isolated colonies of similar morphology from an overnight agar plate. Emulsify in sterile saline or broth to achieve a turbidity equivalent to a 0.5 McFarland standard (approximately 1-2 × 10^8 CFU/mL for most organisms) [1].

Inoculation: Within 15 minutes of standardization, dip a sterile cotton swab into the inoculum suspension. Express excess fluid by rotating the swab against the inside of the tube. Streak the entire surface of a Mueller-Hinton agar plate three times, rotating approximately 60° between streaks to ensure even distribution [1].

Disk Application: Allow inoculated plates to stand at room temperature for 3-15 minutes before applying antibiotic disks. Using sterile forceps or an automated dispenser, place disks firmly onto the agar surface to ensure complete contact. Place disks no closer than 24 mm from center to center [1].

Incubation: Invert plates and incubate at 35±2°C in an ambient air incubator for 16-24 hours. Incubate Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus faecalis for a full 24 hours when testing for oxacillin and vancomycin resistance, respectively [1].

Reading and Interpretation: After incubation, measure the diameter of each zone of inhibition to the nearest millimeter using calipers or an automated reading system. Compare measurements to current CLSI or EUCAST breakpoint tables to categorize isolates as susceptible, intermediate, or resistant [1].

Broth Microdilution Reference Method

As the reference standard for MIC determination, broth microdilution requires meticulous attention to technical details [2]:

Panel Preparation: Prepare antimicrobial agents in cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth at twice the desired final concentration. Dispense 100 μL volumes into wells of sterile microdilution trays. Include growth control (no antibiotic) and sterility control (no inoculum) wells in each tray [2].

Inoculum Standardization: Adjust the turbidity of a log-phase broth culture or saline suspension of colonies to match a 0.5 McFarland standard. Further dilute the suspension 1:150 in broth to achieve a final inoculum of approximately 5 × 10^5 CFU/mL [2].

Inoculation: Add 100 μL of the standardized inoculum to each well of the microdilution tray, resulting in a 1:1 dilution of the antibiotic and the final target inoculum of 5 × 10^5 CFU/mL. Seal trays to prevent evaporation during incubation [2].

Incubation: Incubate trays at 35±2°C for 16-24 hours in an ambient air incubator. Certain fastidious organisms may require extended incubation or supplemented media [2].

Reading Endpoints: Examine trays for visible growth after incubation. The MIC is the lowest concentration of antimicrobial agent that completely inhibits visible growth. Note that a small button of growth at the bottom of the well or slight haziness should be considered as no growth for tetracyclines and sulfonamides, which exhibit partial inhibition [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of conventional phenotypic AST requires carefully controlled materials and reagents. The following table details essential components of the AST research toolkit:

Table 2: Essential research reagents and materials for conventional phenotypic AST

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specification Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| Mueller-Hinton Agar [1] | Growth medium for disk diffusion and agar dilution | pH 7.2-7.4; calcium 20-25 mg/L; magnesium 10-12.5 mg/L; thymidine content <0.03 μg/mL |

| Cation-Adjusted Mueller-Hinton Broth [1] [2] | Liquid medium for broth dilution methods | Calcium 20-25 mg/L; magnesium 10-12.5 mg/L |

| Antimicrobial Powder/Disks [1] | Active pharmaceutical ingredients | Known potency and purity; stored according to manufacturer specifications |

| McFarland Standards [1] | Inoculum density standardization | 0.5 McFarland (1.5 × 10^8 CFU/mL); verified periodically by quantitative colony counts |

| Quality Control Strains [1] [2] | Method verification | American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) strains with defined susceptibility profiles (e.g., E. coli ATCC 25922, S. aureus ATCC 29213) |

Quality control represents an essential component of reliable AST, requiring daily testing of QC strains when performing patient testing and each time a new lot of reagents or media is put into use [1] [2]. Results for QC strains must fall within established ranges before patient or research results can be reported. Additionally, proper storage of antimicrobial agents—particularly frozen stocks of powders and prepared solutions—is critical for maintaining stability and potency [1].

Conventional phenotypic AST methods continue to provide the foundation for antimicrobial susceptibility testing despite decades of technological advancement. Their enduring value lies in their comprehensive detection of resistance mechanisms—whether genetically mediated or expressed phenotypically—without requiring prior knowledge of underlying genetic determinants [1] [2]. While automated and rapid systems offer significant advantages in turnaround time, conventional methods remain essential for reference testing, method validation, and specialized applications [4] [5].

For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the principles, performance characteristics, and methodological details of conventional phenotypic AST is crucial for designing robust studies, interpreting susceptibility data, and validating novel diagnostic approaches. These methods provide the evidentiary foundation for establishing interpretive criteria for new antimicrobial agents and tracking the evolution of resistance patterns over time [1] [2]. As the global threat of antimicrobial resistance continues to escalate, conventional phenotypic AST will maintain its central role in both clinical management and public health surveillance of resistant infections.

In the ongoing global battle against antimicrobial resistance (AMR), the ability to accurately determine a pathogen's susceptibility to antibiotics is a cornerstone of effective treatment and antimicrobial stewardship. While molecular methods are rapidly advancing, phenotypic Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST) remains the definitive reference for assessing how a bacterium will respond to a drug in a clinical setting [6]. Among these phenotypic methods, three techniques are widely regarded as gold standards: disk diffusion, broth microdilution, and the E-test. These methods provide the critical data that guide therapeutic decisions, from the community clinic to the intensive care unit.

The continued relevance of these techniques is underscored by the limitations of genotypic approaches. As one review notes, "a carbapenemase gene is identifiable in fewer than 50% of bacteria found to be phenotypically carbapenem resistant" [7]. This highlights the indispensable role of phenotypic methods in capturing the complex expression of resistance, regardless of the underlying genetic mechanism. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of these three foundational AST methods, framing them within the broader context of traditional versus molecular AST research for an audience of scientists, researchers, and drug development professionals.

Methodological Principles and Experimental Protocols

Disk Diffusion (Kirby-Bauer Test)

Principle: This method assesses bacterial susceptibility by measuring the zone of inhibition around an antibiotic-impregnated disk on an agar surface. The diameter of the zone, where bacterial growth has been prevented, is inversely correlated with the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) of the antibiotic [8].

Detailed Experimental Protocol:

- Inoculum Preparation: A standardized inoculum of the bacterial isolate is prepared, typically to a turbidity of 0.5 McFarland standard (approximately 1-2 x 10^8 CFU/mL for Enterobacterales) [8].

- Inoculation: The surface of a Mueller-Hinton agar plate is uniformly inoculated with the bacterial suspension using a sterile cotton swab.

- Disk Application: Antibiotic-impregnated paper disks are aseptically placed on the inoculated agar surface.

- Incubation: Plates are inverted and incubated at 35±2°C for 16-24 hours under ambient air.

- Reading and Interpretation: After incubation, the diameter of the complete inhibition zone is measured to the nearest millimeter. The results are interpreted as Susceptible (S), Intermediate (I), or Resistant (R) based on guidelines published by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) or the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) [8].

Broth Microdilution

Principle: This dilution-based method determines the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) – the lowest concentration of an antimicrobial agent that prevents visible growth of a microorganism. It involves incubating a standardized bacterial inoculum in a series of wells containing doubling dilutions of an antibiotic [9].

Detailed Experimental Protocol:

- Panel Preparation: A microtiter plate with pre-dispensed, serial two-fold dilutions of antibiotics is used. These can be prepared in-house or purchased commercially.

- Inoculum Preparation: A bacterial suspension is adjusted to a standard turbidity (0.5 McFarland) and then further diluted in broth medium (e.g., Mueller-Hinton broth) to achieve a final inoculum of approximately 5 x 10^5 CFU/mL in each well [9].

- Inoculation: Each well of the panel is inoculated with the standardized bacterial suspension.

- Incubation: The panel is covered and incubated at 35±2°C for 16-24 hours.

- Reading and Interpretation: The MIC is read as the lowest concentration of antibiotic that completely inhibits visible growth. The MIC value is then categorized as S, I, or R using appropriate clinical breakpoints [10].

Gradient Diffusion (E-Test)

Principle: The E-test combines elements of both diffusion and dilution principles. A predefined, stable, and continuous exponential gradient of an antibiotic is immobilized on a plastic strip. When placed on an inoculated agar plate, the antibiotic is released immediately, creating a gradient of concentrations in the agar. The MIC is read where the ellipse of inhibition intersects the strip [11].

Detailed Experimental Protocol:

- Inoculum Preparation and Inoculation: This step is identical to the disk diffusion method. An agar plate is inoculated with a standardized bacterial suspension.

- Strip Application: The E-test strip, labeled with a concentration scale, is placed onto the inoculated agar surface with the antibiotic gradient facing downward.

- Incubation: The plate is inverted and incubated at 35±2°C for 16-24 hours.

- Reading and Interpretation: After incubation, the MIC is read directly from the scale on the strip at the point where the edge of the inhibition ellipse intersects it [11].

Comparative Performance Analysis

The following tables summarize the key characteristics and performance data of the three gold standard methods, synthesizing information from comparative studies and reviews.

Table 1: Key Characteristics and Performance Metrics of Gold Standard AST Methods

| Feature | Disk Diffusion | Broth Microdilution | E-Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principle | Diffusion-based [8] | Dilution-based [9] | Gradient diffusion [11] |

| Result Output | Qualitative (S/I/R) [8] | Quantitative (MIC) [9] | Quantitative (MIC) [11] |

| Turnaround Time | 16-24 hours [8] | 16-24 hours [9] | 16-24 hours [11] |

| Approx. Cost per Test | $2 - $5 [8] | Higher (commercial panels) | Higher (commercial strips) |

| Ease of Use | Simple, no specialized equipment needed [8] | Moderate, can be automated | Simple, no specialized equipment needed |

| Throughput | High | High (especially with automation) | Low to moderate (suitable for single agents/isolates) |

| Key Advantage | Cost-effective, flexible, good for screening [8] | Reference quantitative method, high throughput [9] [10] | Provides MIC directly from agar-based testing [11] |

| Key Limitation | Does not provide an MIC [8] | Labor-intensive if manual, higher cost | More expensive per test, not ideal for high-throughput [11] |

Table 2: Experimental Performance Data from Comparative Studies

| Study Context | Disk Diffusion Performance | Broth Microdilution (Reference) | E-Test Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detecting Vancomycin Resistance in Enterococci (Scandinavian Study) | Sensitivity: 93% (VME* rate: 7.0%); Specificity: 98% (ME rate: 2.4%) [12] | CLSI Agar Screen: Sensitivity: 93% (VME rate: 6.6%); Specificity: 94% (ME rate: 5.6%) [12] | Not tested in this study |

| Antifungal Susceptibility Testing for Aspergillus spp. | Poor correlation with broth microdilution [11] | Reference method (CLSI M38-A) [11] | Essential agreement* with BMD: 69-85% across antifungals [11] |

| Testing on Early Growth Isolates (for Gram-positive bacteria) | Demonstrated acceptable performance in previous reports [9] | For Enterococcus spp.: 6.8% minor error rate, 0.09% major error rate, no very major errors [9] | Not tested in this study |

*VME: Very Major Error (false susceptible); ME: Major Error (false resistant); *Essential Agreement: MIC within ±2 dilutions.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The successful execution of these gold standard methods relies on a suite of critical reagents and materials. The following table details these essential components and their functions in the AST workflow.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Gold Standard AST

| Reagent/Material | Function in AST | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Mueller-Hinton Agar/Broth | The standard medium for non-fastidious aerobic bacteria for both diffusion and dilution tests [12] [8]. | Must comply with CLSI/EUCAST specifications for cation concentration and pH. Performance can vary between manufacturers (e.g., BBL vs. Oxoid vs. Merck) [12]. |

| Antibiotic Disks | Impregnated with a defined amount of antibiotic for disk diffusion tests [8]. | Stability and storage conditions are critical. Disks must be from certified suppliers and used before expiration. |

| Broth Microdilution Panels | Plastic trays with pre-dispensed, serial dilutions of antibiotics for MIC determination [9]. | Available commercially (e.g., Thermo Fisher Sensititre) or can be custom-made. Essential for high-throughput, standardized testing. |

| E-Test Strips | Plastic strips with a predefined, continuous antibiotic gradient for MIC determination on agar [11]. | Available for a wide range of antibiotics and antifungal agents. More costly per test than disks. |

| Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) Agar | Used in specific screening methods, such as the CLSI agar screen for vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) [12]. | The agar base must be carefully selected, as performance can differ (e.g., Difco BHI performed significantly better than Oxoid BHI in one study) [12]. |

| Standardized Inoculum Systems | (e.g., McFarland standards, turbidity meters, automated colony pickers) To ensure a precise and consistent bacterial inoculum for all methods [8]. | Inoculum density is a critical variable affecting the accuracy and reproducibility of zone sizes and MICs. |

Workflow Integration and Logical Pathways

The selection and application of each AST method depend on the specific laboratory context and requirements. The diagram below outlines the decision-making workflow for implementing these gold standard methods.

Discussion: Gold Standards in a Molecular World

The data clearly illustrate that disk diffusion, broth microdilution, and E-test each occupy a distinct and vital niche in the AST landscape. Disk diffusion remains unparalleled for its cost-efficiency and flexibility in routine susceptibility screening and resistance surveillance [8]. Broth microdilution stands as the definitive reference quantitative method, essential for confirming MICs, testing novel compounds, and generating high-quality data for drug development and epidemiological studies [9] [10]. The E-test elegantly bridges the gap between these two, offering the practicality of an agar-based test with the quantitative output of an MIC, making it particularly valuable for confirming resistance in specific isolates or for testing antibiotics not available in commercial panels [11].

The strengths of these phenotypic methods become most apparent when contrasted with molecular techniques. Phenotypic AST is "hypothesis-free," capturing the net effect of all resistance mechanisms—known, unknown, and combined—in a single result that directly predicts clinical response [7] [6]. This is a significant advantage over targeted molecular tests, which can only detect the specific resistance genes they are designed to find.

However, the 16-24 hour turnaround time inherent to these growth-dependent methods is a significant limitation in acute care settings. This has spurred innovations such as "early growth AST" (egAST), where isolates incubated for only 6 hours are used in broth microdilution systems, reducing turnaround time by up to 18 hours without significantly compromising accuracy [9]. Furthermore, the field is moving toward integration. Modern clinical microbiology increasingly relies on a synergistic approach: using rapid molecular or mass spectrometry tools for initial pathogen identification and resistance gene detection, while relying on phenotypic gold standards for definitive confirmation and to guide final therapeutic adjustments [13] [6].

Disk diffusion, broth microdilution, and E-test form an indispensable triad of phenotypic AST methods. Despite the exciting rise of molecular diagnostics, these techniques continue to provide the definitive measure of antimicrobial susceptibility, validating new genetic resistance findings and ensuring patient care is guided by biologically relevant data. For researchers and drug developers, a deep understanding of the principles, performance, and appropriate application of these gold standards is fundamental to advancing the fight against antimicrobial resistance. Their role in validating next-generation rapid technologies and ensuring the accuracy of antimicrobial efficacy data will remain critical for the foreseeable future.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) represents one of the most urgent global public health threats of the 21st century, with projections estimating up to 10 million annual deaths attributable to AMR by 2050 if rigorous measures are not implemented [2]. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST) stands as a critical laboratory function for guiding appropriate antimicrobial therapy, tracking resistance trends, and informing stewardship interventions [2] [1]. For decades, conventional phenotypic methods—including disk diffusion, broth microdilution, and agar dilution—have constituted the cornerstone of AST in clinical microbiology laboratories, providing the reference standard against which all newer technologies are validated [2] [1]. These methods directly measure bacterial response to antimicrobial agents, delivering a phenotypic result that reflects the net effect of all resistance mechanisms present in the microorganism.

However, a significant paradigm shift is underway, moving from pure phenotypic analysis toward genotypic profiling. This molecular shift is driven by the protracted turnaround times (often up to 48-72 hours from specimen collection) inherent to traditional culture-based methods, which necessitate multiple cultivation steps to obtain pure isolates [2] [14] [15]. During this diagnostic window, clinicians must rely on empirical broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy, which contributes to the selection of resistant pathogens and unfavorable patient outcomes [15]. The emerging molecular arsenal offers the potential to dramatically compress this timeline, in some cases providing results within hours, thereby enabling more precise and timely therapeutic decisions [7] [14]. This guide objectively compares the performance of traditional phenotypic and molecular genotypic AST methods, providing the experimental data and context essential for researchers and drug development professionals navigating this evolving landscape.

Methodological Comparison: Foundational Principles and Performance Metrics

The fundamental distinction between phenotypic and genotypic AST methods lies in what they measure. Phenotypic methods assess the observable growth response of bacteria to antibiotics, typically determining the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)—the lowest concentration of an antimicrobial that prevents visible growth [2] [1]. In contrast, genotypic methods detect specific genetic determinants known to confer resistance, such as resistance genes (e.g., mecA, bla genes for ESBLs, carbapenemases) or mutations [2] [16].

Table 1: Core Principles and Outputs of AST Methodologies

| Feature | Traditional Phenotypic Methods | Molecular Genotypic Methods |

|---|---|---|

| What is Measured | Bacterial growth inhibition in presence of antibiotic [1] | Presence of specific resistance genes or mutations [16] |

| Primary Output | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC), categorized as S/I/R [1] | Detection/identification of genetic resistance markers |

| Key Advantage | Functional assessment of resistance, regardless of mechanism [1] | Rapid turnaround time (hours) [14] |

| Key Limitation | Long turnaround time (often >24 hours after isolation) [2] | Detects only targeted, known mechanisms; may not equate to expression [2] |

Performance Data and Validation

The translation of these fundamental principles into laboratory practice yields significant differences in performance metrics. A comprehensive review of over 90 rapid AST technologies, including both phenotypic and genotypic platforms, highlighted that while innovation is robust, extensive validation is required before these methodologies can be fully integrated into routine clinical practice [7]. The following table summarizes critical performance characteristics based on current literature and technological assessments.

Table 2: Comparative Performance of AST Methodologies

| Performance Characteristic | Traditional Phenotypic | Molecular Genotypic |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Turnaround Time (from pure culture) | 16-24 hours (standard) / 6-8 hours (automated) [14] | 1-6 hours [2] |

| Mechanism Coverage | Comprehensive, hypothesis-free [1] | Limited to targeted probes/assays [2] |

| Essential Agreement with Reference BMD | Gold standard [2] | Variable; high for specific gene targets [16] |

| Capacity for Direct Specimen Testing | Challenging (inoculum, mixed cultures) [17] | Possible and increasingly implemented [17] [16] |

| Quantitative Result | Yes (MIC) [1] | Typically qualitative or semi-quantitative |

For specific pathogens, the performance of molecular methods is particularly notable. In Helicobacter pylori, for instance, molecular assays can detect point mutations associated with clarithromycin resistance (e.g., in the 23S rRNA gene) directly from gastric biopsies, providing a valuable tool for guiding eradication therapy [16]. However, a significant limitation is that genotypic methods may overestimate resistance if a resistance gene is detected but not expressed, or if the resistance is mediated by a novel or untargeted mechanism [2]. This is exemplified by the fact that a carbapenemase gene is identifiable in fewer than 50% of bacteria found to be phenotypically carbapenem resistant [7].

Experimental Protocols: A Closer Look at Key Techniques

Reference Phenotypic Method: Broth Microdilution

The Broth Microdilution (BMD) method is widely considered the reference standard for phenotypic AST against which all other methods are validated [2] [1].

Detailed Protocol:

- Inoculum Preparation: Several colonies of a pure, overnight bacterial culture are suspended in saline or broth to a turbidity equivalent to a 0.5 McFarland standard (~1-2 x 10^8 CFU/mL). This suspension is then further diluted in a standardized broth medium (e.g., Mueller-Hinton Broth) to achieve a final concentration of approximately 5 x 10^5 CFU/mL [1].

- Plate Setup: A microtiter plate is used, where each well contains a predefined, serial two-fold dilution of an antimicrobial agent in broth. One well serves as a growth control (no antibiotic), and another as a sterility control (no inoculum) [1].

- Inoculation and Incubation: Each well of the plate is inoculated with the standardized bacterial suspension. The plate is sealed and incubated under standardized conditions (35±2°C, ambient air) for 16-20 hours [1].

- Result Interpretation: The MIC is determined visually as the lowest concentration of antimicrobial that completely inhibits visible growth. This MIC value is then interpreted as Susceptible (S), Intermediate (I), or Resistant (R) using CLSI or EUCAST clinical breakpoints [1].

Genotypic Method: PCR-Based Detection of Resistance Genes

Protocols for detecting specific resistance genes, such as mecA in Staphylococcus aureus or carbapenemase genes in Enterobacterales, follow a general workflow that can be adapted for real-time or conventional PCR.

Detailed Protocol:

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Bacterial cells from a pure colony or directly from a clinical specimen (e.g., positive blood culture broth) are lysed. DNA is then purified using a commercial extraction kit, which may be manual or automated [16].

- Primer and Probe Design: Sequence-specific oligonucleotide primers and, for quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR), fluorescently-labeled probes are designed to bind to unique, conserved regions of the target resistance gene(s). Multiplex panels can be designed to detect several genes simultaneously [14] [16].

- Amplification: The reaction mix containing the extracted DNA template, primers, probes, nucleotides, and a thermostable DNA polymerase is subjected to thermal cycling. In qPCR, the accumulation of the amplification product is monitored in real-time by measuring the fluorescence signal released from the probes [16].

- Result Analysis: The cycle threshold (Ct) value, which indicates the number of cycles required for the fluorescence signal to exceed a background level, is determined. A sample is considered positive for the target resistance gene if its Ct value falls below a validated cutoff, indicating successful amplification [16].

Signaling Pathways and Logical Workflows

The logical progression from a suspected infection to a definitive AST result differs significantly between conventional and modern workflows. The following diagram illustrates the critical path and timeframes for each approach, highlighting where time savings are achieved.

A key advantage of molecular methods is their ability to bypass the lengthy culture and isolation steps, directly interrogating the genetic material in a sample. The core principle of these methods relies on detecting specific sequences within known resistance mechanisms. The following diagram generalizes the molecular logic for detecting antibiotic resistance genes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Implementing and researching AST methods, particularly molecular techniques, requires a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key components essential for experimental work in this field.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular AST

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation | Example Application in AST |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | For lysing bacterial cells and purifying DNA/RNA from clinical specimens or bacterial colonies. | Preparation of template for PCR-based detection of resistance genes from positive blood cultures [14]. |

| PCR Master Mix | A pre-mixed solution containing thermostable DNA polymerase, dNTPs, MgCl₂, and reaction buffers. | Essential for amplifying target resistance genes (e.g., mecA, vanA, carbapenemase genes) in conventional or real-time PCR [16]. |

| Sequence-Specific Primers & Probes | Short, synthetic oligonucleotides designed to bind complementary to specific resistance gene sequences. | Enable specific amplification and detection of target genes. Hydrolysis (TaqMan) probes are common in qPCR for multiplexed assays [16]. |

| Positive Control DNA | Genomic DNA from a strain known to harbor the target resistance gene(s). | Critical for validating the performance of each PCR run and ensuring reagents are functioning correctly [16]. |

| Standardized Culture Media (e.g., Mueller-Hinton Agar/Broth) | Defined media that ensures reproducible and comparable growth of non-fastidious organisms for phenotypic AST. | Used as the foundation for reference methods like disk diffusion, agar dilution, and broth microdilution [1]. |

| Antimicrobial Powders/Disks | Pure, quantified antimicrobial agents for incorporation into agar or broth, or impregnated onto filter paper disks. | Used to create the concentration gradient or diffusion field required to determine MIC or zone diameter [1]. |

The molecular shift in AST represents a transformative advancement in clinical microbiology, offering unprecedented speed in detecting antimicrobial resistance. However, the transition from phenotype to genotype is not a simple replacement but an evolution toward a more integrated, nuanced diagnostic paradigm. While molecular methods provide exceptional speed and specificity for known targets, phenotypic methods retain the irreplaceable advantage of being a comprehensive, hypothesis-free assessment of bacterial behavior under antimicrobial pressure [2] [1]. The future of AST lies not in the supremacy of one approach over the other, but in their strategic combination. Rapid genotypic screening can guide early, targeted therapy, which may later be refined or confirmed by comprehensive phenotypic profiling. This synergistic approach, supported by continued innovation in automation, microfluidics, and sequencing, holds the greatest promise for effectively combating the global AMR crisis and improving patient outcomes [7] [14] [15].

The relentless rise of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) represents one of the most severe threats to global public health, with projections suggesting it could cause 10 million annual deaths by 2050 [1]. The cornerstone of effective antimicrobial stewardship and successful patient outcomes is rapid and reliable Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST), which guides clinicians in selecting the most appropriate antibiotics [18] [1]. However, conventional phenotypic AST methods, often considered the gold standard, require a minimum of 72 hours from specimen collection to final results [7]. This critical time lag forces clinicians to rely on empirical therapy, contributing to antibiotic misuse, treatment failures, and the escalation of AMR [1] [7]. This article frames the urgent need for speed in AST within a comparative analysis of traditional and molecular methods, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a clear understanding of the current technological landscape and its driving innovations.

Table: The Impact of Delayed AST Results on Patient and Public Health

| Aspect | Consequence of Delay | Long-Term Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Patient Treatment | Delayed administration of effective therapy; continued use of inappropriate empiric antibiotics [7]. | Increased mortality, particularly in sepsis; longer hospital stays [7]. |

| Antimicrobial Stewardship | Inability to de-escalate therapy in a timely manner [17]. | Increased selective pressure, driving the emergence of resistant pathogens [1]. |

| Public Health | Hindered detection and monitoring of emerging resistance patterns [18]. | Limited effectiveness of public health interventions and policy guidelines [18]. |

Conventional Phenotypic AST: The Established Benchmark with Inherent Limitations

Conventional phenotypic methods determine a microorganism's susceptibility by observing its ability to grow in the presence of antimicrobial agents. The most widely used techniques include disk diffusion, broth dilution, and gradient diffusion (E-test) [1]. These methods provide a measure of the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC), the lowest concentration of an antibiotic that prevents visible growth, which is then interpreted as Susceptible (S), Intermediate (I), or Resistant (R) based on guidelines from the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) and the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) [1].

Experimental Protocols and Workflow

The standard broth microdilution method, a reference quantitative technique, follows a rigorous protocol [1]:

- Inoculum Preparation: A pure bacterial colony is suspended in a saline or broth medium. The turbidity is adjusted to a 0.5 McFarland standard, equating to approximately 1-2 x 10^8 Colony Forming Units (CFU)/mL.

- Dilution and Dispensing: The antimicrobial agent is serially diluted (often twofold) in a broth medium across the wells of a microtiter plate.

- Inoculation and Incubation: Each well is inoculated with a standardized volume of the adjusted bacterial suspension. The plate is then sealed and incubated at 35±2°C for 16-20 hours under appropriate atmospheric conditions.

- Reading and Interpretation: The MIC is determined by visually inspecting the wells for the absence of turbidity. The MIC value is compared to established clinical breakpoints to assign a categorical result (S, I, or R).

Despite their reliability, these methods are labor-intensive and possess a long turnaround time because they require prior isolation of pure bacterial colonies, which typically adds 24 hours to the process [1] [7]. Furthermore, they are limited by the need for manual interpretation and challenges in standardizing the inoculum [1].

Diagram 1: Workflow of conventional phenotypic AST methods, highlighting the multi-step, time-consuming process that contributes to the diagnostic bottleneck.

Molecular and Genotypic AST: Speed with a Narrow Focus

Molecular AST methods detect specific genetic markers, such as resistance genes (e.g., mecA for methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus) or mutations, using techniques like polymerase chain reaction (PCR), DNA microarrays, and whole-genome sequencing (WGS) [18] [1]. The primary advantage of these methods is their rapid turnaround time, which can provide results in a matter of hours, directly from clinical specimens in some cases [17].

Performance Comparison with Traditional Methods

Table: Comparison of Conventional Phenotypic vs. Molecular Genotypic AST Methods

| Feature | Conventional Phenotypic Methods | Molecular Genotypic Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Measures bacterial growth inhibition [1]. | Detects specific resistance genes or mutations [1]. |

| Time-to-Result | ~72 hours from specimen [7]. | A few hours [17]. |

| Key Advantage | Functional, hypothesis-free assessment of susceptibility [7]. | Exceptional speed. |

| Key Limitation | Long turnaround time, labor-intensive [1]. | Limited target range; cannot detect novel or complex resistance mechanisms [7]. |

| Therapeutic Guidance | Directly informs on drug efficacy. | Indirect, based on genotype-phenotype correlation. |

| Application in Routine Labs | Widespread, gold standard [1]. | Primarily for specific pathogens (e.g., MRSA, MDR-TB) and research [1]. |

A significant limitation of genotypic methods is that they are not hypothesis-free. They can only detect the specific resistance mechanisms they are designed to target. For instance, a 2024 review noted that a carbapenemase gene is identifiable in fewer than 50% of bacteria found to be phenotypically carbapenem-resistant, highlighting a major gap in their predictive capability [7]. This makes them powerful supplements but not yet standalone replacements for phenotypic testing in routine clinical practice.

The Innovative Frontier: Next-Generation Rapid Phenotypic AST

The pressing need to shorten the AST timeline has catalyzed innovation in rapid phenotypic technologies. These platforms aim to retain the comprehensive, hypothesis-free nature of phenotypic testing while drastically reducing the time-to-result. A 2024 scoping review identified over 90 rapid phenotypic AST technologies in the development pipeline, leveraging diverse technical innovations [7].

Key Technology Categories and Methodologies

- Direct-from-Specimen Testing: These methods bypass the need for pure colony isolation by performing AST directly on patient samples like positive blood cultures or urine. The main challenge is standardizing the inoculum and managing polymicrobial samples [17].

- Microfluidics and Microdroplets: These technologies confine bacteria into picoliter- or nanoliter-sized droplets, drastically reducing the volume needed for analysis. This reduction increases the effective bacterial concentration, enabling detection of micro-colony growth within just 30 minutes to 4 hours using high-resolution imaging [1] [7].

- MALDI-TOF MS AST: While primarily used for identification, Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry is being explored for AST by monitoring protein profile changes in bacteria exposed to antibiotics over a few hours [18] [1].

- Automated Digital Microscopy and Cytological Analysis: Advanced systems use time-lapse imaging and AI-powered software to monitor morphological changes and cell lysis in bacteria upon antibiotic exposure at the single-cell level, providing results in 2-4 hours [7].

Experimental Protocol: Microdroplet Growth Assay (DOT-MGA)

A prime example of a cutting-edge rapid phenotypic method is the Direct-On-Target Microdroplet Growth Assay (DOT-MGA) [1]:

- Sample Preparation: A bacterial suspension from a positive blood culture is prepared and encapsulated into thousands of nanoliter-sized droplets in an oil-emulsion mixture.

- Antibiotic Exposure: The droplet library is dispensed onto a substrate pre-patterned with a concentration gradient of different antibiotics.

- Incubation and Imaging: The platform is incubated for a short period (e.g., 30-120 minutes) and monitored with automated, high-throughput time-lapse microscopy.

- Growth Analysis: AI-driven image analysis software detects and quantifies micro-colony growth within each droplet. The MIC is determined by identifying the lowest antibiotic concentration that inhibits growth.

This method's power lies in its ability to perform high-throughput, single-cell analysis, compressing a process that traditionally takes a day into a couple of hours.

Validation and Implementation: The Path to Clinical Adoption

For any new AST technology to be adopted, it must undergo rigorous validation. A framework adapted from government agencies helps classify the Technology Readiness Level (TRL) of these platforms, ranging from basic principle observation (TRL 1-3) to clinical validation and commercial deployment (TRL 7-9) [7]. A 2024 review of the pipeline found that while 18 platforms have been commercialized (with FDA clearance or CE marking), the vast majority of the 81 non-commercialized technologies are still in the proof-of-concept or prototype stages (TRL 3-5) [7].

Furthermore, a standardized framework for the Phase of Clinical Validation is critical for assessing maturity. This spans from analytical feasibility studies (Phase I) to large-scale, multi-center clinical trials that assess impact on patient outcomes and antimicrobial stewardship (Phase IV) [7]. Most emerging technologies have not yet advanced to the latter stages, indicating a significant opportunity for further development and investment.

Diagram 2: Combined framework for evaluating rapid AST technologies, showing progression in Technology Readiness Level (TRL) and Phase of Clinical Validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The development and execution of both conventional and novel AST methods rely on a suite of critical reagents and materials.

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

| Reagent/Material | Function in AST | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Cation-Adjusted Mueller-Hinton Broth (CAMHB) | The standardized growth medium for broth microdilution, ensuring consistent ion concentration for antibiotic activity [1]. | Conventional broth microdilution; reference method for validating new assays. |

| Mueller-Hinton Agar (MHA) Plates | The standardized solid medium for agar-based diffusion and dilution methods [1]. | Disk diffusion testing; agar dilution MIC determination. |

| ATCC Quality Control Strains | Reference strains (e.g., S. aureus ATCC 25923, E. coli ATCC 25922) with known susceptibility profiles for daily quality control [1]. | Verifying performance and accuracy of AST reagents, equipment, and procedures. |

| Antimicrobial Powder Standards | High-purity antibiotics for preparing in-house stock solutions and dilution series [1]. | Creating custom antibiotic panels for research; broth/agar dilution methods. |

| Microtiter Plates | Multi-well plates, often 96-well, used for high-throughput broth microdilution assays [1]. | Conventional MIC testing; automated AST systems. |

| Microfluidic Chips/Cartridges | Miniaturized devices with microchannels and chambers for manipulating fluids at the nano/picoliter scale [1] [7]. | Rapid phenotypic AST using microdroplets or single-cell analysis. |

The "Urgent Need for Speed" in the AMR crisis is the paramount driver of innovation in the AST landscape. While conventional phenotypic methods remain the gold standard for their comprehensive, hypothesis-free nature, their slow turnaround time is a critical liability. Molecular methods offer unparalleled speed but are constrained by their narrow, targeted approach. The most promising future lies in next-generation rapid phenotypic technologies that leverage microfluidics, advanced imaging, and AI to deliver reliable, comprehensive susceptibility profiles in a fraction of the time. For researchers and drug developers, the focus must be on advancing these technologies through robust clinical validation (Phases III-IV) and overcoming implementation barriers to fully realize their potential for transforming patient care and stemming the tide of antimicrobial resistance.

Methodologies in Action: A Deep Dive into Traditional and Molecular AST Workflows

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST) is a critical methodology in clinical and research microbiology used to determine the sensitivity of a microorganism to specific antimicrobial agents. The results, reported as Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations (MICs), guide therapeutic decisions by identifying the lowest concentration of an antibiotic that prevents visible microbial growth [19]. In the context of a broader thesis examining traditional versus molecular AST methods, understanding the classic broth microdilution technique is foundational. While novel molecular methods offer speed, classic phenotypic methods like broth microdilution remain the reference standard for determining microbial susceptibility, providing a direct measure of bacterial response to antibiotics that genotypic methods cannot fully replicate [6] [19]. This guide provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for executing the classic broth microdilution method, from culture preparation to MIC interpretation.

Workflow Visualization: From Culture to Result

The diagram below illustrates the key steps in the classic broth microdilution workflow and highlights where a modern molecular method intersects, offering a potential reduction in time-to-result.

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol

The following section details the standard broth microdilution method as endorsed by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) [19].

Materials Preparation

- Cation-Adjusted Mueller Hinton Broth (CA-MHB): Serves as the growth medium, with cations ensuring consistent antibiotic activity [19].

- Antibiotic Stock Solutions: Prepare high-concentration stocks in appropriate solvents (e.g., water, dimethyl sulfoxide) and filter-sterilize.

- Sterile Tubes or Plates: Use 14 mL polypropylene round-bottom tubes for macrobroth dilution or 96-well microtiter plates [19].

- Saline Solution: 0.9% sodium chloride for bacterial suspension.

Broth Microdilution Procedure

Prepare Antibiotic Dilution Series

- Create a two-fold serial dilution of the antibiotic in CA-MHB. For a typical test, prepare a concentration series that is twice the desired final concentration, as it will be diluted upon bacterial inoculation [19]. For example, to test a final range of 1 µg/mL to 64 µg/mL, prepare stock solutions from 2 µg/mL to 128 µg/mL.

- Include a growth control tube/well containing CA-MHB without antibiotic.

Standardize Bacterial Inoculum

- Select 3-5 well-isolated colonies from an overnight agar plate (e.g., Brain-Heart Infusion Agar).

- Suspend the colonies in saline and adjust the turbidity to a 0.5 McFarland standard, which equates to approximately 1-2 x 10^8 CFU/mL [19].

- Perform a 1:150 dilution of this suspension in CA-MHB to achieve a final inoculum density of approximately 5 x 10^5 CFU/mL [19].

Inoculate and Incubate

- Add 1 mL of the standardized bacterial inoculum to each 1 mL of antibiotic dilution and the growth control [19]. This step halves the antibiotic concentration, resulting in the desired final concentration range.

- Incubate the tubes or plates at 35 ± 2°C for 16-20 hours under ambient air, with shaking if using tubes [19].

Read and Interpret MIC

- After incubation, examine each tube/well for visible turbidity.

- The Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) is defined as the lowest concentration of antibiotic that completely inhibits visible growth of the organism [19].

- Compare the MIC value to the interpretive standards (breakpoints) provided by organizations like CLSI or EUCAST to categorize the organism as Susceptible, Intermediate, or Resistant.

Comparative Performance Data: Classic vs. Molecular

The table below summarizes a direct comparison between the classic broth microdilution method and the molecular Enzymatic Template Generation and Amplification (ETGA) method, based on experimental data [19].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Classic Broth Microdilution and Molecular ETGA AST Methods

| Performance Metric | Classic Broth Microdilution | Molecular ETGA Method |

|---|---|---|

| Time to MIC Result | 20-24 hours [19] | 4-6 hours [19] |

| Agreement with Reference | (Reference Standard) | 100% agreement at 4, 6, and 22 hours for tested organisms (E. coli, S. aureus) [19] |

| Methodology Basis | Phenotypic (visible growth inhibition) | Functional (measurement of bacterial DNA polymerase activity) [19] |

| Key Application | Gold standard for routine AST and validation | Rapid screening, potential for same-day treatment guidance [19] |

| Throughput & Automation | Manual or semi-automated systems (e.g., Sensititre) [20] | Amenable to automation and integration with qPCR systems [19] |

The data demonstrates that while the classic method is the foundation of AST, molecular methods like ETGA can produce equivalent results in a fraction of the time. A 2013 feasibility study showed that ETGA could generate MICs for E. coli and S. aureus from spiked blood cultures in as little as 4-6 hours, with results showing complete agreement with the 22-hour broth microdilution reference method [19]. This significant reduction in turnaround time can profoundly impact clinical decision-making, especially in critical cases like sepsis.

Table 2: Experimental MIC Results for S. aureus and E. coli Strains: Classic vs. ETGA

| Bacterial Strain | Antibiotic | Reference MIC (Classic Broth, µg/mL) | ETGA MIC (4-6 hours, µg/mL) | Agreement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus (MSSA) ATCC 29213 | Oxacillin | 0.25 | 0.25 | Yes [19] |

| S. aureus (MRSA) NRS241 | Oxacillin | >256 | >256 | Yes [19] |

| S. aureus (MSSA) ATCC 29213 | Vancomycin | 1 | 1 | Yes [19] |

| E. coli ATCC 25922 | Ciprofloxacin | 0.015 | 0.015 | Yes [19] |

| E. coli ATCC 25922 | Tetracycline | 1 | 1 | Yes [19] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

A successful AST experiment relies on specific, high-quality materials. The following table details key components used in the classic broth microdilution workflow [19].

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Broth Microdilution AST

| Item | Function/Description | Example from Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Cation-Adjusted Mueller Hinton Broth (CA-MHB) | Standardized growth medium; cations (Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺) ensure accurate expression of antibiotic activity [19]. | Primary test medium for non-fastidious bacteria. |

| Macrodilution Tubes | Vessels for housing the antibiotic dilutions and bacterial culture during incubation [19]. | 14 mL polypropylene round-bottom tubes. |

| 0.5 McFarland Standard | Turbidity standard used to calibrate the initial bacterial inoculum density to ~1.5x10^8 CFU/mL [19]. | Essential for achieving a final inoculum of ~5x10^5 CFU/mL. |

| Brain-Heart Infusion (BHI) Agar | A general, nutritious non-selective agar for the propagation and isolation of bacterial strains prior to AST [19]. | Used for growing fresh colonies of S. aureus and E. coli. |

| Sterile Saline (0.9%) | An isotonic solution used to create the initial bacterial suspension from agar plates without causing osmotic shock [19]. | Used for preparing the 0.5 McFarland suspension. |

For laboratories seeking to streamline parts of this workflow, commercial systems like the Sensititre System offer a mix of manual, semi-automated, and fully automated solutions for inoculum preparation (e.g., nephelometer), plate inoculation (e.g., programmable pipettes), incubation, and fluorometric or digital reading of results [20].

In the ongoing battle against infectious diseases and the global threat of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), the accuracy and speed of pathogen detection are paramount [21]. Traditional methods, particularly in Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST), have long relied on microbiological culture and phenotypic techniques such as disk diffusion and broth microdilution to determine the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) of antibiotics [21]. While these methods are standardized and cost-effective, they are inherently labor-intensive and slow, requiring 24 to 48 hours to yield results after the initial culture [21] [22]. This delay can critically impact patient management, leading to the empirical overuse of antibiotics and contributing to the rise of AMR [21] [22].

The development and implementation of molecular technologies represent a paradigm shift for clinical microbiology [23]. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), and more specifically real-time PCR and multiplex panels, have revolutionized diagnostic workflows by enabling the rapid, sensitive, and simultaneous detection of multiple pathogens directly from clinical specimens [24] [23]. This article provides a comparative guide to these molecular tools, framing them within the broader thesis of transitioning from traditional to molecular AST methods. We will objectively compare the performance of various commercial multiplex panels, supported by experimental data, and detail the protocols and reagents that form the core of this modern molecular arsenal.

The Evolution of PCR in Diagnostics

Real-time PCR, also known as quantitative PCR (qPCR), is a sensitive and reliable method for gene expression analysis and pathogen quantification [25]. Unlike conventional PCR, which provides end-point analysis, real-time PCR quantitatively monitors the amplification of DNA in real-time through the use of fluorescent reporter molecules [26]. The cycle number at which the fluorescence crosses a predefined threshold (the Ct value) is the primary metric, which correlates directly with the initial amount of target nucleic acid [25].

The natural progression from detecting a single target is multiplex real-time PCR. This technique allows for the amplification of multiple DNA or RNA targets simultaneously in a single reaction [26]. This requires a specific pair of primers and a complementary DNA-binding probe for each target, with each probe labeled with a spectrally distinct fluorophore [26].

Advantages and Challenges of Multiplexing

The benefits of multiplexing are substantial for a clinical or research laboratory:

- Increased Throughput & Efficiency: Multiple targets can be assessed from a single sample in one reaction, saving time, reagents, and labor [27] [26].

- Comprehensive Data: Provides a broader diagnostic picture, which is crucial for syndromes with overlapping symptoms, such as respiratory or gastrointestinal infections [28] [23].

- Conservation of Sample: Maximizes data obtained from limited or precious sample material [26].

- Improved Data Normalization: An internal control can be included in each well to control for inhibition and pipetting errors [26].

However, multiplexing introduces technical challenges. The main pitfalls include competition for reagents between targets, which can skew the quantification of low-abundance targets, and the risk of undesired interactions between the numerous primers and probes in the reaction mix [26]. Careful experimental design, including meticulous primer/probe design and extensive validation, is required to ensure each reaction in the multiplex operates with equal efficiency [26].

Comparative Performance Evaluation of Commercial Multiplex Panels

To objectively assess the landscape of available molecular tools, we turn to published comparative studies. The diagnostic performance of a multiplex panel is primarily measured by its sensitivity (ability to correctly identify positive samples) and specificity (ability to correctly identify negative samples).

Comparison of Gastrointestinal Parasite Panels

A 2019 study provided a direct, head-to-head evaluation of four commercial multiplex real-time PCR assays for detecting diarrhoea-causing protozoa: Cryptosporidium hominis/parvum, Giardia duodenalis, and Entamoeba histolytica [24] [29]. The study used a reference panel of 126 well-characterized DNA samples to assess diagnostic performance [24].

Table 1: Diagnostic Sensitivity of Four Commercial Multiplex qPCR Assays for Enteric Protozoa [24] [29]

| Multiplex PCR Method | Manufacturer | Cryptosporidium hominis/parvum Sensitivity (%) | Giardia duodenalis Sensitivity (%) | Entamoeba histolytica Sensitivity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RIDAGENE Parasitic Stool Panel | R-Biopharm | 87.5% | 91.5% | Similarly detected by all methods |

| Gastroenteritis/Parasite Panel I | Diagenode | 78.1% | 68.1% | Not detected |

| Allplex GI Parasite Panel 4 | Seegene | 75.0% | 93.6% | Similarly detected by all methods |

| FTD Stool Parasites | Fast Track | 53.1% | 100% | Similarly detected by all methods |

The data reveals that performance varies significantly depending on both the method used and the targeted pathogen [24]. The R-Biopharm assay demonstrated the best performance for Cryptosporidium, while the Fast Track assay was superior for Giardia [24] [29]. The study also highlighted differences in the limit of detection; the R-Biopharm method showed a 100-fold better detection limit for Cryptosporidium than other tests, while the Fast Track method had at least a 10-fold superior limit for Giardia [24]. These findings underscore that no single method is universally superior, and factors like targeted pathogens and local epidemiology must guide selection.

Concordance in Respiratory Virus Panels

Respiratory infections represent another major application for multiplex panels. A 2024 study compared the performance of three PCR-based platforms for detecting SARS-CoV-2, Influenza A/B, and Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) [28].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Respiratory Multiplex PCR Panels [28]

| Multiplex PCR Platform | Type | Overall Agreement with Comparator | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| TrueMark SARS-CoV-2, Flu A, Flu B, RSV | Laboratory-Developed Test (LDT) | 100% | 100% concordance with OpenArray LDT and BioFire RP2.1 |

| Open Array Respiratory Panel | Laboratory-Developed Test (LDT) | 100% | 100% concordance with TrueMark LDT and BioFire RP2.1 |

| BioFire Respiratory Panel 2.1 (RP2.1) | FDA-Approved IVD | 100% | Full concordance with both LDTs for nasopharyngeal samples |

This study demonstrates that well-validated laboratory-developed tests can achieve performance on par with FDA-approved in vitro diagnostic (IVD) tests [28]. The 100% concordance across all four respiratory viruses indicates that these multiplex tests can be confidently implemented in clinical settings for the accurate diagnosis of co-circulating respiratory pathogens [28].

Experimental Protocols for Multiplex Panel Evaluation

To ensure reliability and reproducibility, the evaluation of multiplex panels follows rigorous experimental protocols. The following workflow generalizes the key steps from the cited studies [24] [29] [28].

Detailed Methodology

1. Sample Collection and DNA Extraction [24] [28]

- Sample Type: The study should use well-characterized clinical samples (e.g., stool for GI panels, nasopharyngeal swabs for respiratory panels) suspended in an appropriate molecular transport medium [24] [28].

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Purification is typically performed using automated systems (e.g., KingFisher Flex Purification System) and commercial kits (e.g., MagMAX viral/pathogen nucleic acid isolation kits) according to the manufacturer's instructions. This ensures high-quality, inhibitor-free DNA/RNA for downstream applications [28].

2. Multiplex Real-time PCR Setup and Execution [24] [29]

- Reaction Composition: Each commercial kit is used in strict accordance with its instructions. A typical reaction includes a preset master mix, specific primer-probe sets, and a defined volume of extracted nucleic acid (e.g., 5-10 µL) in a final reaction volume (e.g., 25 µL) [24] [29].

- Controls: Each run must include appropriate negative (no-template) controls, positive controls for each target, and internal controls to detect PCR inhibition [24].

- Amplification Protocol: The reaction is run on a suitable real-time PCR cycler (e.g., Corbett Rotor-Gene 6000, Bio-Rad CFX96, Agilent Mx3005P) with a standardized thermal cycling profile. This usually includes an initial activation step, followed by 40-45 cycles of denaturation, and a combined annealing/extension step [24] [28].

3. Data Analysis and Validation [24] [25]

- Ct Value Assignment: The cycle threshold (Ct) for each sample and target is determined by the instrument's software.

- Sensitivity/Specificity Calculation: Results are compared against a predefined reference standard (e.g., a well-characterized sample panel or a composite standard). Diagnostic sensitivity and specificity are calculated using standard formulas [24].

- Limit of Detection (LOD): The detection limit is determined by testing serial dilutions of a positive sample and identifying the last dilution that yields a positive result [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation and validation of multiplex PCR require a suite of reliable reagents and tools. The following table details key components used in the featured experiments and the broader field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Multiplex PCR [24] [28] [27]

| Item | Function | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Purifies DNA/RNA from complex clinical samples, removing PCR inhibitors. | MagMAX Viral/Pathogen Nucleic Acid Isolation Kits; automated systems like KingFisher Flex are standard [28]. |

| Multiplex PCR Master Mix | A optimized buffered solution containing DNA polymerase, dNTPs, and MgCl₂, formulated for efficient co-amplification of multiple targets. | Commercial mixes are pre-optimized to reduce primer-dimer formation and manage reagent competition [26]. |

| Primer & Probe Sets | Sequence-specific oligonucleotides that define the targets for amplification and detection. | TaqMan-style probes (5'-fluorophore, 3'-quencher) are standard for multiplexing. Designed to be specific and have distinct melting temperatures [27] [26]. |

| Commercial Multiplex Panels | Pre-designed and validated sets of primers and probes for simultaneous detection of a defined group of pathogens. | e.g., RIDAGENE Parasitic Stool Panel, Allplex GI Parasite Panel, TrueMark Respiratory Panels. Available as pre-spotted plates or single tubes [24] [27]. |

| Fluorescent Dyes & Quenchers | Reporters that generate the measurable signal proportional to amplicon production. | Fluorophores: FAM, HEX, Cy5, Texas Red. Must be spectrally distinct for multiplexing [27] [26]. |

| Positive Control Materials | Validates assay performance and helps monitor for contamination. Can be purified pathogen nucleic acids or non-infectious recombinant plasmids. | Chimeric plasmid DNA (cpDNA) can be designed to include multiple target sequences and even a contamination indicator probe [30]. |

The Future: Integrating AI and Advanced Technologies into AST

The evolution of molecular diagnostics continues, with the next frontier being the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML). These technologies promise to further revolutionize AST and infection control.

AI and ML models can be trained to predict pathogen antibiotic resistance and drug sensitivity by analyzing vast datasets, including clinical imaging, genomic sequences, and laboratory results [22]. This can provide rapid decision support to clinicians, potentially reducing the reliance on empirical antibiotic therapy and optimizing treatment choices long before traditional phenotypic AST results are available [22].

Furthermore, advancements in microfluidic technology, single-cell analysis, and next-generation sequencing (NGS) are pushing the boundaries of detection speed and multiplexing capability [21] [22]. These technologies, combined with the robust foundation of real-time PCR and multiplex panels, form a powerful molecular arsenal poised to meet the growing challenges of infectious diseases and antimicrobial resistance in the 21st century.

The escalating challenge of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has intensified the demand for rapid, accurate diagnostic tools. Conventional antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) methods, while reliable, are often tedious, with high turnaround times (TAT) of up to several days [31]. This delay compels clinicians to prescribe empirical, broad-spectrum therapies, which can exacerbate the spread of AMR and increase patient mortality and healthcare costs [31]. The pressing need to prolong the lifespan of current antibiotics has catalyzed the development of next-generation tools. This guide objectively compares three pivotal technologies—Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS), Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS), and Microfluidics—that are reshaping the landscape of clinical microbiology and AST. Framed within the broader thesis of traditional versus molecular methods, this analysis provides researchers and drug development professionals with critical performance data and experimental protocols to inform their work.

Technology Comparison at a Glance

The table below provides a high-level comparison of the core next-generation tools against conventional methods.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of AST Diagnostic Technologies

| Technology | Principle of Operation | Key AST Applications | Typical Turnaround Time (after isolate) | Key Advantage | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Phenotypic [31] | Measures bacterial growth in presence of antibiotics (e.g., broth microdilution, disk diffusion). | Gold standard for Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) determination. | 16–24 hours [7] | Provides definitive, phenotypic results. | Slow; high TAT leads to empirical therapy. |

| Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) [31] | Comprehensive sequencing of the entire bacterial genome to identify resistance genes and mutations. | Detection of known antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs); outbreak surveillance; hypothesis-free analysis. | 1–3 days (varies with workflow) [31] | Unbiased detection of all known resistance determinants. | Does not detect novel resistance mechanisms or provide MIC; requires bioinformatics expertise. |

| MALDI-TOF MS [32] [33] | Proteomic analysis of microbial ribosomal protein profiles for identification and resistance biomarker detection. | Bacterial/fungal identification; detection of specific resistance enzymes (e.g., β-lactamase activity). | Minutes to a few hours [32] [33] | Extremely rapid and low-cost identification. | Limited to detecting specific, known resistance biomarkers. |

| Microfluidics [31] [34] | Miniaturization of assays to manipulate picoliter-nanoliter volumes in microchannels for single-cell analysis. | Rapid phenotypic AST; single-cell analysis; combined with other methods for enhanced sensitivity. | 2–4 hours [7] | Drastically reduced TAT for phenotypic results; low reagent use. | Mostly in research and development phase; not yet widely commercialized. |

Performance and Experimental Data

Resolution and Identification Capabilities

A critical metric for any diagnostic tool is its ability to correctly identify organisms at the species and strain level.

Table 2: Comparison of Identification Resolution

| Technology | Identification Resolution | Supporting Experimental Data |

|---|---|---|

| WGS | Considered the gold standard for resolution, enabling strain-level tracking [35]. | In a study of Bacillus isolates, WGS successfully provided species-level identification for 9 out of 14 isolates (64%) [35]. |

| MALDI-TOF MS | High species-level resolution, comparable to WGS for many common pathogens [35]. | The same study on Bacillus isolates found MALDI-TOF MS correctly identified 13 out of 15 isolates (87%) at the species level [35]. For mycobacteria, a multicentre study reported 100% concordance for M. tuberculosis (43/43) and 85% for slow-growing NTM (42/48) [36]. |

| Conventional Methods (e.g., VITEK 2) | Lower resolution, often unable to differentiate closely related species [35]. | The identification of closely related species like those in the Bacillus genus or the HACEK group is challenging, with biochemical methods identifying less than 77% of HACEK isolates in one study [37]. |

Speed and Cost-Efficiency

Turnaround time and cost are decisive factors for clinical implementation.

Table 3: Comparison of Operational and Economic Factors

| Factor | WGS | MALDI-TOF MS | Microfluidics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time-to-Result (from pure colony) | 1-3 days [31] | Minutes for identification [32]; 2-4 hours for specific β-lactamase AST [33] | 2-4 hours for phenotypic AST [7] |

| Approximate Cost per Test | ~$400 per isolate (library building) [35] | <$1 per isolate for identification [35] | Information varies; aims for cost-effectiveness but R&D costs are high. |

| Throughput | High, but data analysis can be a bottleneck. | High-throughput; hundreds of isolates per hour [35] | Variable; designed for high-throughput single-cell analysis. |

| Technology Readiness | Established in reference labs and for outbreak surveillance. | Routinely implemented in clinical labs for identification; AST applications emerging. | Over 90 technologies in development; mostly in research phase [7]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

MALDI-TOF MS for Detection of β-Lactamase Activity

This protocol is used to rapidly detect carbapenemase production directly from positive blood cultures or bacterial isolates [33].