Unlocking Microbial Dark Matter: Advanced Co-Cultivation Techniques for Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of co-cultivation techniques designed to overcome the challenges of cultivating difficult-to-grow microorganisms, a significant bottleneck in natural product discovery.

Unlocking Microbial Dark Matter: Advanced Co-Cultivation Techniques for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of co-cultivation techniques designed to overcome the challenges of cultivating difficult-to-grow microorganisms, a significant bottleneck in natural product discovery. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the ecological principles underpinning microbial interactions and details practical methodological setups, from liquid-liquid systems to synthetic communities. The content further addresses critical troubleshooting strategies for maintaining system stability and validates the approach through comparative metabolomic assessments and systematic frameworks for analyzing co-culture outcomes, highlighting its proven role in activating cryptic biosynthetic pathways for novel therapeutic leads.

The Principle and Promise: Why Co-Cultivation Awakens Silent Genes

Mimicking Nature: Moving Beyond Axenic Culture Limitations

Axenic culture, the practice of cultivating a single microbial species in isolation, has long been a fundamental methodology in microbiology. However, this approach presents significant limitations for studying the vast majority of microorganisms that thrive in complex, interactive communities. In natural environments, microbial metabolic pathways are often regulated by complex signaling cascades influenced by external factors and neighboring organisms [1]. The absence of these biotic and abiotic incentives in axenic cultures results in chemically poorer profiles and fails to support the growth of an estimated 70–80% of gut microbes and many abundant aquatic prokaryotes [2] [3]. This application note details co-cultivation techniques designed to overcome these limitations by mimicking natural microbial interactions, enabling researchers to isolate difficult-to-culture microorganisms and discover novel metabolic pathways.

Co-Cultivation Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Liquid-Liquid Co-Culture for Gut Microbiome Isolates

Protocol: Isolation of Difficult-to-Culture Gut Bacteria Using Liquid-Liquid Co-Culture

- Sample Preparation: Suspend fresh fecal samples (0.5 g) in 4.5 ml of degassed PBS and dilute to 10−3 under anaerobic conditions [2].

- Supporting Bacteria (SB) Inoculation: Inoculate one side of a horizontal co-culture vessel (e.g., UniWells Horizontal Co-Culture Plate) with 50 µl of the diluted fecal sample as growth-supporting bacteria [2].

- Target Microbe Preparation: Prepare a filtered bacterial solution containing target microbes by passing the diluted fecal sample through a 0.45 µm or 0.22 µm pore size filter to remove larger cells while allowing metabolites and smaller bacteria to pass through [2].

- Co-Culture Setup: Add 1,450 µl of appropriate anaerobic medium (YCFA, mGAM, or Ruminococcus albus media) to each well. Inoculate the opposite side of the co-culture vessel with 50 µl of the filtered bacterial solution. Insert a membrane filter (0.1–0.3 µm pore size) between the chambers to allow metabolite exchange while maintaining physical separation [2].

- Control Setup: Prepare a monoculture control by inoculating 50 µl of the filtered bacterial solution into 1,450 µl of medium in a separate vessel [2].

- Incubation and Monitoring: Culture for 2 days in an anaerobic chamber at 37°C under H₂/CO₂/N₂ (0.5:0.5:9 volume ratio). Monitor growth through turbidity measurements and plate 100 µl of the co-culture solution onto various agar media for colony formation assessment [2].

Table 1: Media Composition for Liquid-Liquid Co-Culture

| Component | YCFA Medium | mGAM Medium | Ruminococcus albus Medium |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base Composition | Specialized for gut microbiota | Modified for gut microbiota | Specific for Ruminococcus |

| Key Characteristics | Contains various carbon sources | Rich in nutrients | Supports cellulolytic bacteria |

| Application | General gut microbiota isolation | Fastidious anaerobic bacteria | Cellulose-degrading bacteria |

Continuous Co-Cultivation for Defined Consortia

Protocol: Establishing Stable Defined Consortia via Continuous Cultivation

- Strain Selection: Select bacterial strains based on complementary metabolic functions to create a division of labor. For carbohydrate fermentation, include primary degraders (e.g., Ruminococcus bromii, Bifidobacterium adolescentis) and secondary metabolite converters (e.g., Phascolarctobacterium faecium, Eubacterium limosum) [4].

- Medium Design: Formulate a defined medium (e.g., PBMF009) containing multiple primary carbohydrate substrates (disaccharides, fructo-oligosaccharides, resistant starch, soluble starch) with minimal undefined ingredients. Maintain low carbon concentrations (1.1–1.3 mg DOC/L) to mimic natural aquatic conditions for oligotrophs [4] [3].

- Inoculation Strategy: Inoculate all selected strains simultaneously in a bioreactor system at predetermined ratios based on predicted growth kinetics [4].

- Continuous Cultivation: Maintain the consortium in continuous culture mode with controlled dilution rates to establish compositional and metabolic equilibrium. For nine-strain consortia, this typically results in a reproducible equilibrium within 1-2 weeks [4].

- Stability Monitoring: Regularly monitor population dynamics through 16S rRNA sequencing, flow cytometry, or strain-specific qPCR assays. Measure metabolic outputs including short-chain fatty acids (acetate, butyrate, propionate) and intermediate metabolites (lactate, formate, succinate) via HPLC or GC-MS [4].

Table 2: Metabolic Division of Labor in a Nine-Strain Consortium (PB002)

| Strain | Primary Metabolic Function | Key Substrates | Key Products |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ruminococcus bromii | Primary degrader (A1, A2) | Complex fibers, starches | Formate, Acetate |

| Bifidobacterium adolescentis | Primary degrader (A1, A2, A4) | Complex carbohydrates | Acetate, Formate, Lactate |

| Phascolarctobacterium faecium | Secondary converter (B5) | Succinate | Propionate |

| Eubacterium limosum | Secondary converter (B1, B3) | Formate, Lactate | Acetate, Butyrate |

| Blautia hydrogenotrophica | Secondary converter (B1), Gas consumer (C2) | Formate, H₂/CO₂ | Acetate |

Signaling Pathways and Microbial Interactions in Co-Cultures

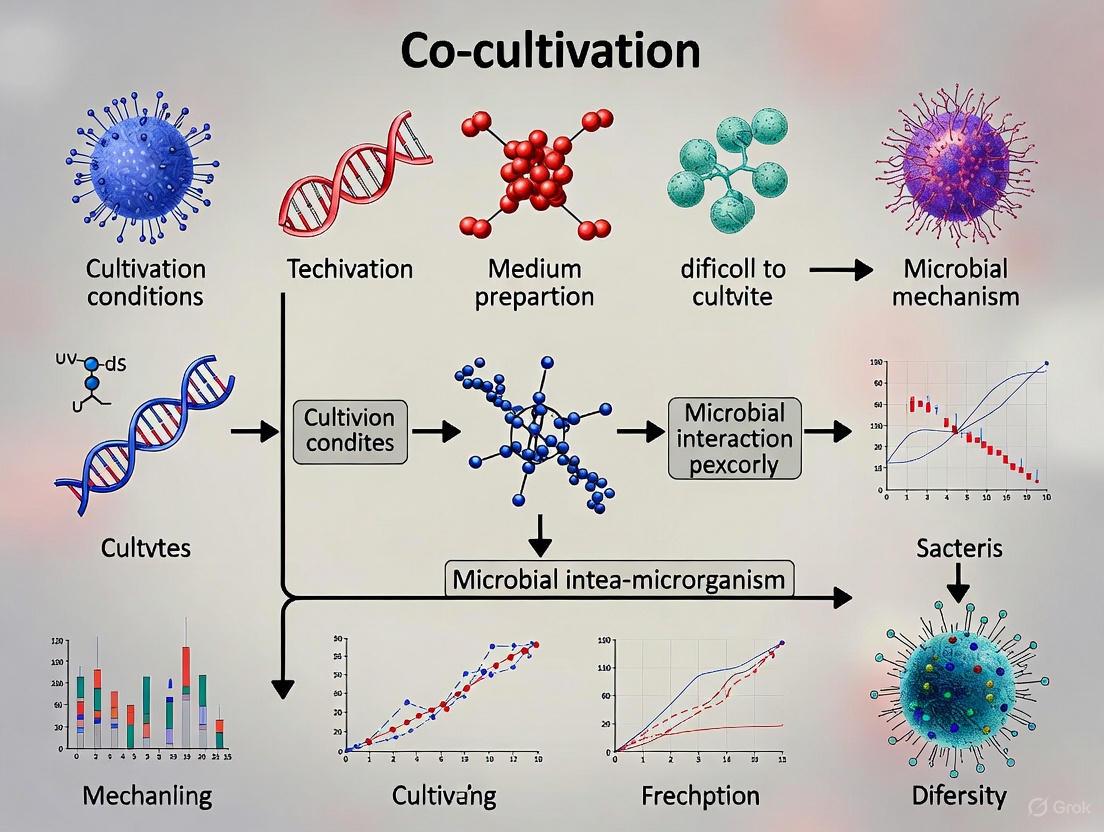

Co-culture systems activate silent biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) through various interaction mechanisms. The diagram below illustrates the major signaling pathways and regulatory networks that enable metabolic induction and community stability in co-culture systems.

These interactions create a dynamic network where microbial communication occurs through:

- Metabolite Exchange: Supporting bacteria provide essential nutrients (organic acids, vitamins) that activate silent biosynthetic gene clusters in target microbes [2] [1].

- Quorum Sensing: Population-dependent signaling molecules coordinate gene expression across the consortium, regulating metabolic pathways and community behaviors [5].

- Feedback Regulation: Newly produced metabolites create feedback loops that further refine the community composition and metabolic output, enhancing stability through mutualistic dependencies [2] [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Co-Cultivation Experiments

| Reagent/Equipment | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Horizontal Co-Culture Vessels | Enables physical separation with metabolite exchange between microbial populations | UniWells Horizontal Co-Culture Plate with membrane filters (0.1–0.3 µm) [2] |

| Anaerobic Chamber Systems | Maintains oxygen-free conditions for obligate anaerobes | Bactron 300 with H₂/CO₂/N₂ (0.5:0.5:9) atmosphere [2] |

| Specialized Media | Supports diverse microbial requirements while mimicking natural conditions | YCFA, mGAM, PBMF009 with defined carbon sources [2] [4] |

| Membrane Filters | Size-based separation of microbial populations and metabolites | 0.1–0.3 µm pore size for metabolite exchange; 0.45 µm for selecting small bacteria [2] |

| Quorum Sensing Reporters | Monitoring microbial communication and population dynamics | Engineered biosensor strains with fluorescent outputs [5] |

Applications and Future Perspectives

Co-cultivation techniques have demonstrated remarkable success in isolating previously uncultivable microorganisms. The liquid-liquid co-culture method has specifically enabled the isolation of Waltera spp., Roseburia spp., and difficult-to-culture strains from human gut samples through symbiotic relationships with supporting bacteria such as Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron and Escherichia coli [2]. In freshwater ecosystems, high-throughput dilution-to-extinction cultivation using defined media has brought previously uncultivated majority into culture, representing up to 72% of genera detected in original environmental samples [3].

The future of co-cultivation research points toward increasingly sophisticated control systems, including cybernetic approaches that use computer-based algorithms to maintain co-culture composition without genetic engineering. These systems leverage natural microbial characteristics (e.g., differential temperature optima) combined with real-time monitoring and actuation to achieve stable co-culture maintenance for extended periods (>250 generations) [6]. Such advances will further accelerate the discovery of novel microbial species and their metabolic products for therapeutic applications.

Application Note & Protocol

Within microbial communities, a complex web of interactions—encompassing competition, antagonism, and symbiosis—governs population dynamics and ecosystem function. For microbiologists, these interactions are not merely ecological observations but powerful tools. Co-cultivation, the practice of growing multiple microbial species together, leverages these interactions as a trigger to unlock the cultivation of the "uncultivated microbial majority" [3]. It is estimated that 70–80% of gut microbes and a significant proportion of environmental prokaryotes remain uncultured using standard methods, primarily because their growth depends on metabolic or signaling inputs from neighboring cells [2] [3]. This application note details protocols and experimental strategies designed to capture these interactions, providing a framework for isolating and studying previously inaccessible microorganisms, with direct applications in live biotherapeutic product (LBP) development and drug discovery.

Key Findings and Quantitative Data

The strategic application of co-culture techniques has successfully isolated a range of difficult-to-culture organisms and enhanced the functionality of synthetic consortia. The quantitative outcomes of these approaches are summarized in the tables below.

Table 1: Key Microorganisms Isulated or Enhanced via Co-cultivation

| Microorganism | Interaction Type | Supporting Microorganism(s) | Key Finding/Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Waltera spp. (Gut) | Symbiosis | Escherichia coli, Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron | Isolated only via liquid-liquid co-culture; growth suppressed on agar [2]. |

| Roseburia spp. (Gut) | Symbiosis | Faecal microbiota (unspecified) | Specifically isolated using liquid-liquid co-culture with faecal samples [2]. |

| Phascolarctobacterium faecium (Gut) | Synergistic Metabolism | Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron | Growth promoted by succinate transfer from B. thetaiotaomicron [2]. |

| Fungus-growing ant Pseudonocardia spp. | Antagonism | Other Pseudonocardia strains | Widespread antagonism between strains shapes host-symbiont dynamics and enforces single-strain rearing [7]. |

| PB002 Synthetic Consortium (9 strains) | Division of Labor | Cross-feeding within consortium | Co-culturing produced a stable, reproducible consortium with distinct growth and metabolic activity versus a mixed culture [4]. |

Table 2: Functional Outcomes of Designed Microbial Consortia

| Consortium/Approach | Functional Coverage | Therapeutic/Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| PB002 (9-Strain Consortium) [4] | 11 of 13 essential carbohydrate fermentation reactions | As effective as Fecal Microbiota Transplant (FMT) in counteracting dysbiosis in a mouse acute colitis model [4]. |

| High-Throughput Dilution-to-Extinction [3] | Up to 72% of genera from original freshwater samples | Isolation of 627 axenic strains, including abundant, previously uncultured oligotrophs, enabling ecological studies [3]. |

| Liquid-Liquid Co-culture Method [2] | Specific isolation of Waltera, Roseburia | Enabled targeted identification of supporting bacteria and their metabolite variations [2]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Liquid-Liquid Co-culture for Isolating Difficult-to-Culture Gut Bacteria

This protocol is designed to isolate bacterial species that require continuous metabolite exchange with supporting bacteria, such as Waltera and Roseburia from human gut samples [2].

I. Materials and Reagents

- Samples: Faecal samples from healthy donors, suspended in degassed PBS.

- Media: YCFA medium (JCM 1130) or mGAM medium (JCM 1461).

- Equipment:

- UniWells Horizontal Co-Culture Plate (or similar vessel with a membrane separator).

- Membrane Filters (0.1 µm, 0.2 µm, 0.3 µm, 0.45 µm pore sizes).

- Anaerobic chamber (e.g., Bactron 300) with atmosphere of H₂/CO₂/N₂ (0.5:0.5:9).

II. Methodology

- Sample Preparation:

- Suspend 0.5 g of fecal sample in 4.5 mL of PBS and degas with nitrogen.

- Serially dilute the sample to 10⁻³.

- To obtain a filtered bacterial fraction, pass a portion of the diluted sample through a 0.45 µm or 0.22 µm pore size filter. This removes larger cells and selects for small, target bacteria.

Co-culture Setup:

- Add 1,450 µL of YCFA medium to each well of the co-culture vessel.

- On one side of the membrane (pore size 0.3 µm), inoculate with 50 µL of the diluted faecal sample (serving as the Supporting Bacteria/SB).

- On the other side of the membrane, inoculate with 50 µL of the filtered bacterial solution (containing the target, difficult-to-culture cells).

- As a control, set up a monoculture of the filtered bacterial solution in a separate well.

- Incubate the co-culture vessels in the anaerobic chamber at 37°C for 48 hours.

Isolation and Identification:

- After incubation, plate 100 µL from the side containing the filtered bacteria onto various agar media.

- Isolate resulting colonies and identify them via 16S rRNA gene sequencing using primers 27F and 1492R.

III. Critical Steps and Troubleshooting

- Filter Pore Size: The 0.3 µm membrane allows for metabolite exchange while preventing physical contact and overgrowth. Using a 0.45 µm filter to prepare the inoculum selects for smaller-sized target cells.

- Metabolite Dependency: If the target organism does not grow with a supernatant from the supporting bacteria, it suggests a requirement for continuous metabolite exchange rather than a one-time nutrient addition [2].

Protocol: LFQRatio Normalization for Quantitative Proteomics in Co-cultures

Understanding microbial interactions requires analyzing proteomic changes in co-culture. This protocol normalizes label-free quantification (LFQ) data to account for changing cell-type ratios [8].

I. Materials and Reagents

- Lysis Buffer: 2% SDS, 40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.5), 60 mM DTT.

- Urea Buffer: 8 M Urea, 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.5), 5 mM DTT (prepare fresh).

- Alkylation Agent: 100 mM iodoacetamide (IAA, prepare fresh and keep in foil).

- Digestion: Sequencing-grade modified trypsin.

- Other Reagents: HPLC-grade water, acetonitrile (ACN), formic acid.

II. Methodology

- Protein Extraction and Digestion:

- Pellet cells from 1.5 mL of co-culture by centrifugation (4,000 g, 10 min).

- Lyse cell pellets in Lysis Buffer with mechanical disruption (e.g., using acid-washed glass beads).

- Reduce proteins with DTT and alkylate with IAA in the dark.

- Perform tryptic digestion after diluting the urea concentration.

Mass Spectrometry Analysis:

- Desalt peptides and analyze by LC-MS/MS using standard gradients.

- Process raw files with a proteomics software (e.g., MaxQuant) for protein identification and LFQ intensity quantification.

LFQRatio Normalization:

- This step addresses bias introduced when the proportions of the co-cultured organisms shift between conditions.

- The LFQRatio method normalizes the LFQ intensity data based on an accurate ratio estimation between the two organisms, improving the reliability of differentially expressed protein identification [8].

III. Application

- This method is crucial for accurately identifying proteins involved in cross-feeding, antagonism, or other interactions, as it corrects for systematic biases in mixed-species samples [8].

Visualization of Workflows and Interactions

The following diagrams, generated using DOT language and a defined color palette, illustrate the core experimental and conceptual frameworks.

Diagram 1: Liquid-liquid co-culture isolation workflow.

Diagram 2: Metabolic division of labor in a consortium.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Microbial Co-culture Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Horizontal Co-culture Vessels | Enables chemical communication between physically separated cultures. | UniWells Horizontal Co-Culture Plate with membrane filters (0.1-0.45 µm) [2]. |

| Defined Isolation Media | Mimics natural low-nutrient conditions to cultivate oligotrophs. | Med2/Med3 for freshwater microbes; YCFA/mGAM for gut microbes [2] [3]. |

| Anaerobic Chamber | Provides strict anaerobic conditions essential for cultivating gut and environmental anaerobes. | Bactron 300 with H₂/CO₂/N₂ atmosphere [2]. |

| Actinomycete Strains | Source of antimicrobial compounds for studying antagonistic interactions. | Pseudonocardia spp. from fungus-growing ant systems [7]. |

| LFQRatio Normalization | Computational/Bioinformatic tool for accurate proteomic analysis of co-cultures. | Normalizes LFQ intensity data from mixed-species samples [8]. |

Awakening Cryptic Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs) for Chemical Diversity

In the genomic era, it has become evident that the biosynthetic potential of microorganisms far exceeds the number of detected natural products under standard laboratory conditions. A significant proportion of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) remain "silent" or "cryptic"—they are not transcribed and do not yield their encoded compounds in pure culture [9]. This represents a vast untapped reservoir of chemical diversity with potential applications in drug discovery and biotechnology. Within the broader context of research on difficult-to-culture microorganisms, co-cultivation has emerged as a powerful, genetics-independent strategy to activate these silent genetic treasures by mimicking the complex ecological interactions found in natural environments [10].

This protocol outlines practical approaches for implementing co-ccultivation techniques to awaken cryptic BGCs, providing application notes and detailed methodologies tailored for researchers and scientists in drug development.

Understanding Cryptic BGCs and Activation Strategies

Biosynthetic gene clusters are sets of co-localized genes that encode the pathways for secondary metabolite production. These clusters can include genes for core biosynthetic enzymes (e.g., NRPS, PKS), tailoring enzymes, regulatory proteins, and resistance mechanisms [11]. Silent BGCs are those that are not expressed under typical in vitro culture conditions, often due to the absence of necessary environmental triggers found in their native habitats [9].

Table 1: Categories of Methods for Activating Silent BGCs

| Category | Rationale | Key Techniques | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endogenous (in native host) | Manipulate the native producer under controlled conditions. | Classical genetics, chemical genetics, culture modalities [9]. | Physiological relevance; investigates native regulation [9]. | Native host may be unculturable; requires genetic tractability [9]. |

| Exogenous (in heterologous host) | Express the entire BGC in a different, amenable host. | BGC refactoring, promoter swapping, fungal shuttle vectors [11] [10]. | Bypasses host-specific regulation; useful for uncultured microbes [10] [9]. | Laborious; size limitations for DNA cloning; host compatibility issues [10] [9]. |

Co-cultivation falls under the category of endogenous, genetics-independent methods. Its fundamental principle is that microbial interactions in nature—such as competition, predation, and symbiosis—serve as powerful evolutionary cues for secondary metabolite production [10]. By cultivating a target microbe in the presence of one or more "helper" or "supporting" strains, these interactions can be recreated in the lab, triggering the activation of otherwise silent pathways [2] [10].

Co-cultivation Experimental Workflow

The following diagram and protocol describe a generalized workflow for a co-cultivation experiment designed to activate cryptic BGCs.

Diagram 1: Co-cultivation Workflow. This flowchart outlines the key stages in a co-cultivation experiment, from initial strain selection to final metabolite characterization.

Protocol: Liquid-Liquid Co-culture for BGC Activation

This protocol is adapted from a study that successfully isolated difficult-to-culture Waltera spp. using a liquid-liquid co-culture method [2].

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Co-culture Vessel | Physically separates cultures while allowing metabolite exchange. | UniWells Horizontal Co-Culture Plate or similar [2]. |

| Membrane Filter | Permeable barrier for chemical signals and metabolites. | 0.1 µm, 0.2 µm, or 0.3 µm pore size [2]. |

| Anaerobic Chamber | Provides a controlled atmosphere for fastidious anaerobes. | E.g., Bactron 300; atmosphere: H₂/CO₂/N₂ (0.5:0.5:9) [2]. |

| Culture Media | Supports growth of target and supporting bacteria. | YCFA (JCM #1130), mGAM (JCM #1461); pre-reduced and degassed [2]. |

| Fecal Sample (optional) | Source of diverse supporting bacteria and metabolites. | Diluted to 10⁻³ in degassed PBS for use as supporting bacteria [2]. |

Procedure

Preparation:

- In an anaerobic chamber, dispense 1.45 mL of the chosen pre-reduced medium (e.g., YCFA) into each well of the co-culture vessel.

- Ensure the membrane filter (e.g., 0.3 µm pore size) is correctly positioned between the two chambers of the vessel.

Inoculation:

- On one side of the vessel, inoculate 50 µL of the supporting bacteria. This can be a single known strain (e.g., Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, Escherichia coli) or a diluted microbial community like a fecal sample [2].

- On the other side of the vessel, inoculate 50 µL of a filtered suspension of the target microorganism. To select for small or specific morphotypes, pass the target culture through a 0.45 µm or 0.22 µm pore size filter [2].

- Prepare a monoculture control of the filtered target microorganism under identical conditions.

Incubation:

- Place the sealed co-culture vessels in an anaerobic chamber maintained at 37°C for 2 days (or as required). Monitor growth visually or via turbidity at 660 nm [2].

Assessment and Isolation:

- After the incubation period, plate 100 µL from the target microorganism's chamber onto solid agar media.

- Incubate the plates for 2 days and assess for colony formation of the target organism, comparing the co-culture condition to the monoculture control [2].

Application Notes

- Strain Selection: The choice of supporting bacteria is critical. It can be based on ecological relevance (e.g., strains from the same habitat) or random screening. In the referenced study, co-culture with diluted fecal samples specifically enriched for B. thetaiotaomicron and E. coli, which were identified as key supporting bacteria for Waltera spp. [2].

- Mechanism of Activation: The activation is often mediated by the exchange of small molecules. Note that simply adding spent supernatant from the supporting bacteria may not be sufficient, as some symbiotic relationships require a continuous, bidirectional exchange of metabolites [2].

- System Flexibility: This liquid-liquid method can be adapted for aerobic organisms by removing the anaerobic steps and using standard incubators.

Complementary and Alternative Activation Methods

While co-cultivation is a powerful ecological mimic, it is one of several strategies in the toolkit for awakening cryptic BGCs. The following diagram illustrates the relationship between these primary approaches.

Diagram 2: BGC Activation Strategies. This diagram categorizes the main strategies for awakening cryptic biosynthetic gene clusters, highlighting the position of co-cultivation among other genetic and chemical approaches.

Ribosome and RNA Polymerase Engineering

This genetics-based approach involves selecting for spontaneous antibiotic-resistant mutants. Mutations in genes encoding ribosomal proteins (e.g., rpsL) or RNA polymerase (e.g., rpoB) can pleiotropically activate silent BGCs by altering cellular physiology and increasing the levels of the alarmone ppGpp, a key trigger for secondary metabolism [12].

- Protocol Outline:

- Spread a dense suspension of the target Streptomyces strain on agar plates containing a sub-inhibitory concentration of an antibiotic (e.g., rifampicin, streptomycin, or gentamicin).

- Incubate until resistant colonies form.

- Screen these mutants for enhanced or novel antibiotic production using agar plate assays against indicator strains or through metabolomic analysis (e.g., HPLC-MS) [12].

- Application Note: The efficiency of this method varies. One study reported activation of antibiotic production in 43% of soil-derived Streptomyces strains tested using this technique [12].

Heterologous Expression

This exogenous strategy involves cloning and transferring a silent BGC from its native host into a well-characterized, genetically tractable host strain [11] [10] [9].

- Protocol Outline:

- Identification and Capture: Identify the target BGC via genome mining (e.g., using antiSMASH). Capture the entire cluster using cosmic or bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) vectors, or synthesize it de novo.

- Refactoring (Optional): Replace native promoters with strong, constitutive inducible promoters to ensure expression in the new host [10].

- Transformation and Screening: Introduce the constructed vector into a platform host such as Streptomyces coelicolor, Aspergillus nidulans, or E. coli and screen for metabolite production [11] [10].

Awakening cryptic biosynthetic gene clusters is a cornerstone of modern natural product discovery. Co-cultivation stands out as a highly effective, physiology-driven method that leverages natural microbial interactions to unlock chemical diversity. When integrated with other genetic, chemical, and synthetic biology approaches, it provides a robust pathway for discovering novel bioactive molecules with potential applications in drug development. The protocols outlined here offer a practical starting point for researchers to integrate these techniques into their discovery pipelines.

The Historical and Ecological Rationale for Mixed Fermentations

Mixed fermentations, defined as processes involving an inoculum of two or more microbial organisms, represent both a historical cornerstone and a forward-looking frontier in biotechnology [13]. For centuries, these processes have been the foundation of traditional food and beverage fermentations, long before the existence of individual microbial species was scientifically understood [13] [14]. In modern research, particularly in the field of difficult-to-culture microorganisms, mixed fermentation or co-cultivation techniques have emerged as a powerful ecological strategy. These approaches leverage natural microbial interactions—such as symbiosis, cross-feeding, and competition—to support the growth of fastidious organisms that resist axenic culture [2]. This application note details the rationale, quantitative ecological dynamics, and practical protocols for implementing mixed fermentations within a research context aimed at drug development and microbiological discovery.

Historical Context and Ecological Advantages

The historical use of mixed cultures is rooted in practicality. Before the development of pure culture techniques by Brefeld and Koch in the 1870s, all microbial fermentations were, by necessity, mixed-culture processes [13]. Early studies referred to them as "symbiotic fermentations" or "mixed infections," reflecting an initial, albeit limited, understanding of their complexity [13]. Traditional products like miso, soy sauce, and a vast array of fermented foods rely on stable, self-regulating microbial consortia that have been maintained through generations, often without a precise knowledge of the constituent microbes [13].

From an ecological perspective, these consortia persist because of the significant advantages they confer upon their members. These advantages form the core rationale for their application in modern co-cultivation research, summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Advantages of Mixed-Culture Fermentations with Ecological and Application Contexts

| Advantage | Ecological Rationale | Research & Application Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Enhanced Product Yield | Synergistic interactions where one organism produces growth factors or enzymes essential for another [13]. | Higher yield of target metabolites (e.g., acids, solvents, pharmaceuticals) compared to single cultures [13]. |

| Multistep Transformations | Division of labor, where different species perform sequential biotransformations [13]. | Enables complex metabolic pathways impossible for a single microbe, creating novel compounds or degrading complex substrates [13]. |

| Stable Microbial Associations | Formation of resilient consortia through continuous metabolite exchange and niche specialization [13] [2]. | Allows for the maintenance of difficult-to-culture species that require specific, continuous metabolic inputs from supporting bacteria [2]. |

| Substrate Utilization | A wider consortium possesses a broader array of enzymes [13]. | Permits the use of complex, cheap, or impure feedstocks (e.g., biomass, botanical drugs) [13] [15]. |

| Protection from Contamination | The combined activity of microbes creates an environment (e.g., low pH, anaerobic conditions, inhibitory compounds) that excludes competitors [13]. | Reduces phage infections and permits open fermentation processes with lower contamination risk [13]. |

These ecological principles are directly applicable to the challenge of cultivating "unculturable" microorganisms. It is estimated that 70–80% of gut microbes remain uncultured, representing a vast reservoir of unexplored biodiversity with potential drug discovery applications [2]. These organisms often lack the genetic capacity to synthesize all necessary growth factors or require the constant removal of inhibitory waste products, needs that are met through symbiotic relationships in a consortium [2].

Table 2: Documented Outcomes of Fermentation on Botanical Drug Precursors

| Botanical Drug | Fermenting Microorganism(s) | Key Pharmacological Improvement | Quantitative Change in Active Components |

|---|---|---|---|

| Panax ginseng | Lactobacillus spp., Monascus spp. (Red yeast rice) | Enhanced anti-diabetic and anti-obesity effects; reduced hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia [15]. | Increased concentrations of ginsenosides Rb1, Rb2, Rc, Rd, Rg3, and Rh2 [15]. |

| Momordica charantia | Lactobacillus plantarum | Improved regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism [15]. | Significant increase in colon short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs): propionic, butyric, and acetic acids [15]. |

| GeGen QinLian Tang | Mixed fermentation | Enhanced hypoglycemic effects compared to unfermented formula [15]. | Improved modulation of TC, TG, LDL-C, HDL-C, and fasting insulin levels [15]. |

| Coix lacryma-jobi | Lactobacillus plantarum NCU137 | Increased nutrient content and reduced hazardous substance [15]. | Increased free amino acids, fatty acids, soluble dietary fiber; reduced 2-pentylfuran [15]. |

Quantitative Ecological Dynamics in Mixed Cultures

The population dynamics in a mixed fermentation are not random but follow predictable ecological models. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for designing and controlling co-culture systems. The Lotka-Volterra (LV) model and its derivatives are commonly used to describe the interaction between two species in a consortium [16].

The generalized form of the model for two species is:

( \frac{dxi}{dt} = \mui xi \left(1 - \left(\frac{xi}{Ki}\right)^{\thetai} - a{i,j} fc(x_j) \right) )

Where:

- ( xi ) and ( xj ) are the cell densities of species ( i ) and ( j ).

- ( \mu_i ) is the specific growth rate of species ( i ).

- ( K_i ) is the carrying capacity for species ( i ).

- ( \theta_i ) controls the non-linearity of intraspecific competition.

- ( a_{i,j} ) is the coefficient of competition, measuring the effect of species ( j ) on species ( i ).

- ( fc(xj) ) is a function describing the type of interspecific competition [16].

The following diagram illustrates the core logical relationships and outcomes governed by these ecological principles in a dual-species consortium.

The model's nullcline analysis reveals how environmental factors like temperature can determine the final outcome of the culture. For example, in mixed cultures of S. cerevisiae and the cryotolerant S. kudriavzevii, successful coexistence is typically only achievable within specific low-temperature ranges; at higher temperatures, S. cerevisiae will competitively exclude the other species [16]. This underlines the importance of controlling process parameters to guide the ecology towards the desired consortium state.

Experimental Protocols for Co-Cultivation

Protocol: Liquid-Liquid Co-Culture for Isolating Difficult-to-Culture Microorganisms

This protocol is designed for the isolation of microorganisms that require metabolic support from other species, as demonstrated by the isolation of Waltera spp. from human gut samples [2].

I. Materials and Equipment

- Anaerobic Chamber (e.g., Bactron 300) with atmosphere of H₂/CO₂/ N₂ (0.5:0.5:9) [2].

- Horizontal Co-Culture Vessels: UniWells Horizontal Co-Culture Plate or similar system with chambers separated by a membrane filter [2].

- Membrane Filters: 0.1 µm, 0.2 µm, 0.3 µm, 0.45 µm pore sizes.

- Culture Media: YCFA (JCM medium 1130), mGAM (JCM medium 1461), or other suitable anaerobic media [2].

- Sample: Fresh fecal or environmental sample, suspended and degassed in PBS.

II. Procedure

- Preparation:

- Add 1,450 µL of pre-reduced culture medium to each well of the co-culture vessel.

- Prepare a 10⁻³ dilution of the sample in PBS.

Inoculation of Supporting Bacteria (SB):

- Inoculate one chamber of the co-culture vessel with 50 µL of the diluted sample. This serves as the community of Supporting Bacteria.

Inoculation of Target Microbiota:

- Prepare a filtered bacterial solution by passing 50 µL of the same sample dilution through a 0.22 µm or 0.45 µm pore size filter. This removes most large cells but allows through small or difficult-to-culture target cells (e.g., small Waltera spp.).

- Inoculate the opposite chamber of the co-culture vessel with this 50 µL filtered solution.

Control Setup:

- Prepare a monoculture control by inoculating a separate vessel with only the 50 µL filtered bacterial solution.

Incubation and Monitoring:

- Insert the specified pore size membrane filter (e.g., 0.3 µm) between the chambers to allow metabolite exchange but prevent cell transfer.

- Place the vessel in the anaerobic chamber and incubate at 37°C for 2-7 days.

- Monitor turbidity in the target cell chamber, which indicates growth promoted by metabolites from the SB chamber.

Isolation and Identification:

- After incubation, streak 100 µL from the target cell chamber onto solid agar media and incubate anaerobically for 2 days to obtain isolated colonies.

- Identify isolates via 16S rRNA gene sequencing using primers 27F and 1492R [2].

The workflow for this isolation strategy is visualized below.

Protocol: Rational Development of a Mixed Yeast Starter for Metabolite Production

This protocol outlines a systematic approach for developing a mixed yeast starter for enhanced metabolite production, as applied in Agave must fermentations [17]. The methodology can be adapted for other fermentation substrates.

I. Strain Selection and Characterization

- Library Assembly: Assemble a collection of yeast strains from the target ecological niche (e.g., fermenting must). Include Saccharomyces and diverse non-Saccharomyces species [17].

- Primary Screening in Semi-Synthetic Medium:

- Culture each strain individually in a defined medium (e.g., M2 with 90 g/L fructose, 10 g/L glucose).

- Analyze after 48 hours for key parameters:

- Sugar Consumption: Measure residual glucose and fructose.

- Ethanol Productivity: Quantify ethanol yield (g/g sugar).

- Volatile Metabolite Profile: Analyze via GC-MS for esters (e.g., ethyl-butyrate, isoamyl acetate) and higher alcohols [17].

II. Mixed Culture Fermentation and Kinetics

- Consortium Design: Based on screening, select strains with complementary attributes (e.g., high-attenuation Saccharomyces, aroma-producing Torulospora and Kluyveromyces).

- Inoculum Ratio Optimization: Test different inoculation ratios (e.g., 0.1:1:1 or 1:1:1 for Saccharomyces: Kluyveromyces: Torulospora) in the target substrate (e.g., Agave tequilana must) [17].

- Population Dynamics Tracking:

- Use strain-specific Fluorescent in situ Hybridization (FISH) probes for qualitative and semi-quantitative analysis of population kinetics throughout fermentation [17].

- Monitor population shifts to ensure the survival of non-Saccharomyces strains over the fermentation timeline.

III. Performance Evaluation

- Compare pure and mixed cultures for final ethanol yield, carbon dioxide production, glycerol, acetic acid, and the final volatile metabolite profile to validate the superior performance of the selected consortium [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Mixed Fermentation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function and Application | Specific Examples and Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Horizontal Co-Culture Vessels | Enables physical separation of microbial populations while allowing free exchange of metabolites and signaling molecules via a membrane [2]. | UniWells Horizontal Co-Culture Plate; membrane pore sizes (0.1-0.45 µm) are critical for isolating specific size-based interactions [2]. |

| Anaerobic Chamber | Provides a controlled, oxygen-free atmosphere essential for cultivating obligate anaerobes, which constitute many difficult-to-culture species [2]. | Bactron 300 with H₂/CO₂/N₂ (0.5:0.5:9) atmosphere [2]. |

| Specialized Culture Media | Supports the growth of fastidious microorganisms by providing essential nutrients, vitamins, and a reducing environment [2]. | YCFA (JCM #1130), mGAM (JCM #1461); media should be pre-reduced for anaerobic work [2]. |

| Strain-Specific FISH Probes | Allows for the identification, quantification, and spatial tracking of specific species within a mixed consortium without the need for culturing [17]. | Critical for elucidating population dynamics and metabolic interactions in real-time during fermentation [17]. |

| qPCR Assays with Species-Specific Primers | Provides highly accurate, quantitative data on the relative and absolute abundance of target species in a mixed culture over time [16]. | Designed on unique gene regions (e.g., BUD3 for differentiating S. cerevisiae and S. kudriavzevii) [16]. |

| Modeling Software for Ecological Dynamics | Fits time-series population data to ecological models (e.g., Lotka-Volterra) to predict interactions and optimize culture conditions [16]. | Used to perform nullcline analysis and identify parameter spaces (e.g., temperature, inoculum) that enable stable coexistence [16]. |

A Practical Toolkit: Designing Effective Co-Culture Systems

Within the context of a broader thesis on co-cultivation techniques for difficult-to-culture microorganisms, this document details the application of a specific liquid-liquid co-culture methodology. It is estimated that 70–80% of gut microbes are uncultured using standard laboratory techniques, a challenge that extends to microbial communities in other environments [2]. Traditional axenic (pure) culture methods often fail to replicate the complex symbiotic relationships and metabolic dependencies that many bacteria rely on in their natural habitats. Co-culture strategies aim to overcome these limitations by cultivating target organisms alongside growth-supporting microbial partners.

The liquid-liquid co-culture method described herein uses a physical membrane to separate two liquid cultures, allowing for the continuous exchange of metabolites and signaling molecules while preventing cell-to-cell contact. This approach has proven particularly effective for isolating fastidious gut bacteria such as Waltera spp. and Roseburia spp., which require continuous metabolic exchange with supporting bacteria like Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron and Escherichia coli for growth [18] [2]. This protocol provides a standardized framework for implementing this technique to access the "uncultured microbial dark matter" from any environment.

Key Principles and Experimental Rationale

The liquid-liquid co-culture system is founded on the principle of simulating natural symbiotic relationships. Many difficult-to-culture bacteria depend on other members of their community for essential growth factors, which can include specific nutrients, the removal of inhibitory waste products, or signaling molecules that regulate gene expression.

- Metabolic Dependency: Target bacteria often lack complete metabolic pathways for synthesizing essential compounds. Supporting bacteria can provide these missing metabolites. For instance, Phascolarctobacterium faecium relies on Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron to produce succinate, which it then utilizes for growth [2].

- Continuous Exchange: A critical finding is that many of these dependencies require continuous interaction. Simply adding spent culture supernatant from supporting bacteria is often insufficient to promote growth of the target organism [18] [2]. The liquid-liquid system maintains a dynamic, real-time exchange of metabolites that mimics the constant flux of a natural ecosystem.

- Size-Based Selection: The method incorporates a filtration step (e.g., using 0.45 µm or 0.22 µm filters) to select for specific cell morphologies or to separate the target bacteria from the original complex community before co-culture [2]. This is particularly useful for isolating small-sized or morphologically unique variants.

Experimental Protocols

Core Liquid-Liquid Co-Culture Setup

The following protocol is adapted from studies that successfully isolated Waltera spp. and Roseburia spp. from human fecal samples [18] [2].

I. Materials and Equipment

- Co-culture Vessel: UniWells Horizontal Co-Culture Plate or a custom-designed vessel with two chambers separated by a recess for a membrane filter.

- Membrane Filters: 0.1 µm, 0.2 µm, 0.3 µm, 0.45 µm pore size filters, sterile.

- Anaerobic Chamber: Maintained at 37°C with an atmosphere of H₂/CO₂/N₂ (volume ratio: 0.5:0.5:9).

- Culture Media: YCFA (JCM medium number 1130), mGAM (JCM medium number 1461), or other suitable anaerobic media.

- Sample Source: Fecal samples suspended and diluted in degassed PBS, or environmental samples.

II. Step-by-Step Procedure

Sample Preparation:

- Suspend 0.5 g of fecal sample in 4.5 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and degas by flushing with nitrogen gas to maintain anaerobiosis.

- Prepare a 10⁻³ dilution of the sample in PBS.

Inoculation:

- Add 1,450 µl of pre-reduced anaerobic medium (e.g., YCFA) to each well of the co-culture vessel.

- On one side of the vessel, inoculate with 50 µl of the diluted fecal sample. This serves as the Supporting Bacteria (SB) compartment.

- On the other side, inoculate with 50 µl of a filtered bacterial solution (the main inoculum passed through a 0.45 µm or 0.22 µm filter to select for small bacteria and remove larger cells).

Assembly and Incubation:

- Carefully place a sterile membrane filter (0.3 µm pore size is often used) between the two chambers of the co-culture vessel.

- Assemble the vessel according to the manufacturer's instructions to ensure a sealed interface.

- Place the entire assembly in an anaerobic chamber and incubate at 37°C for 2 days.

Subculturing and Isolation:

- After 2 days, harvest 100 µl from the compartment containing the filtered bacterial solution.

- Inoculate onto various suitable agar media and incubate anaerobically for another 2 days to obtain isolated colonies.

- Colonies can be identified via 16S rRNA gene sequencing using primers 27F and 1492R [2].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of this core protocol:

Protocol for Identifying Supporting Bacteria and Metabolites

Once a target isolate is obtained, the following sub-protocol can be used to identify the key supporting bacteria and the metabolites involved in the symbiotic relationship.

Co-culture with Defined Strains:

- Co-culture the selected small-sized target isolate (e.g., filtered Waltera spp.) with single, defined bacterial strains (e.g., B. thetaiotaomicron, E. coli) in the liquid-liquid system to confirm their supporting role [18].

Metabolite Analysis:

- Co-culture the supporting bacteria and the target isolate, and collect the culture supernatant at different time points (e.g., 12, 24, 36, 48 h). Centrifuge (4,000 × g, 10 min) and filter (0.22 µm) the samples to obtain the co-culture supernatant.

- Prepare a control supernatant from the target isolate in monoculture.

- Analyze the supernatants using non-targeted metabolomics approaches, such as Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry (UPLC-TOF-MS) [19] [20].

- Identify metabolites that are significantly depleted in the co-culture supernatant compared to the control, indicating consumption by the target isolate.

Functional Validation of Metabolites:

- Add the identified, depleted metabolites individually or in combination to the culture medium of the target isolate in monoculture.

- Assess whether the addition of these metabolites can replace the need for co-culture, enabling axenic growth. Failure to grow often indicates a requirement for continuous metabolite exchange or other dynamic interactions [2].

Data Presentation and Analysis

Quantitative Data from Model Studies

Table 1: Bacterial Species Isolated Using Liquid-Liquid Co-culture from Fecal Samples [2]

| Isolate | Source | Key Supporting Bacteria Identified | Growth Requirement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Waltera spp. | Multiple human fecal samples | Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, Escherichia coli | Requires continuous liquid-liquid co-culture; does not grow on agar co-culture or with supernatant alone. |

| Roseburia spp. | Multiple human fecal samples | Not specified in results | Specifically isolated via this method. |

| Phascolarctobacterium faecium | Human fecal sample | Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron | Utilizes succinate produced by B. thetaiotaomicron. |

Table 2: Summary of Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Horizontal Co-culture Vessel | Provides a physical platform for two liquid cultures to share metabolites via a permeable membrane. | UniWells Horizontal Co-Culture Plate [2]. |

| Membrane Filters | Allows diffusion of metabolites and small molecules while physically separating the two microbial populations. | Pore sizes of 0.1 µm, 0.2 µm, 0.3 µm, and 0.45 µm are used for selection and separation [2]. |

| Anaerobic Culture Media | Supports the growth of obligate anaerobic bacteria, which are common among difficult-to-culture microbes. | YCFA medium, mGAM medium [2]. |

| Metabolomics Tools | Identifies and quantifies changes in the metabolite profile to understand symbiotic interactions. | UPLC-TOF-MS (Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry) [19] [20]. |

Applications and Broader Context

The liquid-liquid co-culture method is a powerful tool within the growing field of microbial culturomics. Its primary application is the expansion of the catalog of cultured microorganisms, which is crucial for:

- Live Biotherapeutic Products (LBPs): Isolating novel bacteria with potential probiotic or therapeutic functions for human health [2].

- Functional Characterization: Moving beyond genomic predictions to experimentally validate the metabolic capabilities and physiological requirements of bacteria.

- Ecosystem Understanding: Elucidating the intricate network of metabolic interactions that define microbial communities in environments ranging from the human gut to soil and marine ecosystems [18] [21].

While this protocol focuses on gut microbiota, the core principle is universally applicable. Similar approaches have been successfully employed to induce the production of novel secondary metabolites in fungal-bacterial co-cultures for drug discovery [19] and to study host-pathogen interactions [22]. The integration of this method with advanced 'omics' technologies—such as dual RNA-seq [22] and metabolomics—creates a robust pipeline for not only isolating the uncultured but also for deeply understanding the molecular basis of their survival.

The isolation and cultivation of challenging microorganisms represent a significant hurdle in microbial ecology and natural product discovery. A profound gap exists between the vast diversity of microbes observed in environmental samples through molecular techniques and the minimal fraction that can be grown in pure culture using standard laboratory methods, a phenomenon known as the "great plate count anomaly" [23]. Co-cultivation has emerged as a powerful strategy to bridge this gap by mimicking the natural, competitive environments from which these microbes originate. In their natural habitats, microorganisms exist within complex communities, engaging in a constant interplay of competition and cooperation mediated by physical contact and chemical signaling [1] [24]. These interactions often regulate the expression of silent biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs), leading to the production of specialized metabolites that are not expressed under standard monoculture conditions [1]. The core premise of this application note is that the strategic selection of microbial partners is not merely a technical step, but a critical determinant for successfully cultivating elusive microbes and unlocking their chemical potential. By recapitulating key ecological interactions in the laboratory, researchers can provide the necessary stimuli to wake "sleeping" cells from dormancy and support their growth [23]. This document provides a structured framework for selecting partner microbes—spanning bacterial-bacterial, fungal-fungal, and cross-kingdom pairings—to enhance success in researching difficult-to-culture microorganisms.

Foundational Principles for Partner Selection

The selection of microbial partners for co-culture should be guided by a set of foundational principles derived from ecological theory and empirical observations. The Stress-Gradient Hypothesis posits that synergistic or cooperative interactions become more frequent and vital in stressful environments [25] [26]. In microbial contexts, nutrient oligotrophy is a key stressor. Research from a phosphorous-oligotrophic aquatic system demonstrated that beneficial interactions dominated in low-nutrient media, whereas antagonistic interactions prevailed in nutrient-rich conditions [25]. This suggests that cross-kingdom synergistic interactions represent an adaptive trait for survival in oligotrophic environments. Consequently, pairing microbes from naturally nutrient-poor environments (e.g., deep sediments, oligotrophic waters) under low-nutrient laboratory conditions can favor cooperative outcomes and growth support.

A second principle involves leveraging Pre-Adapted Interactions from shared habitats. Microbes originating from the same ecological niche are more likely to have established pre-adaptive interactions, whether competitive or cooperative. Utilizing such naturally co-occurring pairs can significantly increase the success rate of co-cultivation. A study on sorghum-associated microbial communities under drought stress found that microbial responses and interactions were most pronounced in the root compartment, followed by the rhizosphere, suggesting these are key niches for identifying strong microbial partnerships [26]. Furthermore, the Interaction-Driven Activation principle states that the physical confinement of two or more microbial strains forces competition for resources and territory, which can induce the activation of otherwise silent biosynthetic pathways [24]. This strategy is not limited to cross-kingdom pairs; fungal-fungal co-cultures have proven exceptionally effective for generating new chemical diversity [24].

Table 1: Strategic Rationale for Selecting Microbial Partners in Co-Culture

| Selection Strategy | Underlying Principle | Expected Outcome | Representative Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Source from Shared, Stressful Niches | Stress-Gradient Hypothesis; pre-adapted interactions | Induction of cooperative survival mechanisms; activation of silent BGCs [25] [26] | Fungi and bacteria from a phosphorus-limited evaporitic basin showed synergistic growth under low-nutrient lab conditions [25]. |

| Pair by Functional Guild | Ecological role similarity; potential for synergy or competition | Discovery of guild-specific metabolites; enhanced substrate degradation | A synthetic cellulose-degrading consortium was created by co-culturing the five most dominant bacterial strains from a natural environment [27]. |

| Combine Phylogenetically Distant Taxa | Niche complementarity; reduced direct competition | Diversification of metabolic profiles; access to unique cross-kingdom metabolites [25] | Co-culture of the bacterium Streptomyces sp. with the fungus Aspergillus nidulans induced production of the polyketide aspercyclide [1]. |

| Utilize Known "Helper" Strains | Provision of essential growth factors or signaling molecules | Growth support for uncultivable taxa; resuscitation from dormancy [2] [23] | Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron and Escherichia coli were identified as key supporters for the growth of difficult-to-culture Waltera spp. from the human gut [2]. |

Practical Pairing Strategies and Experimental Workflows

Bacterial-Bacterial Pairings

Bacterial-bacterial co-cultures are widely used to isolate and study difficult-to-culture species from complex communities. A key methodology is the liquid-liquid co-culture system, which facilitates metabolite exchange while maintaining physical separation. A seminal protocol successfully isolated novel Waltera spp., Roseburia spp., and Phascolarctobacterium faecium from human fecal samples [2]. The workflow involves using a horizontal co-culture vessel separated by a membrane filter (0.1–0.3 µm pore size) that permits the passage of metabolites but not cells. The "supporting bacteria" (SB)—in this case, a diluted fecal sample—are inoculated on one side, while the filtrate (containing the difficult-to-culture, small-sized target bacteria) is inoculated on the other. The success of this method hinges on the continuous exchange of metabolites between the SB and the target isolate [2]. Metabolomic analysis of the co-culture supernatant can then be used to identify the specific nutrients and metabolites being consumed, providing clues about the growth dependencies of the target organism.

Fungal-Fungal Pairings

Fungal-fungal co-culture is a premier strategy for generating chemical diversity, as the competitive interaction activates silent biosynthetic gene clusters [24]. The rationale for pairing strains can be based on several factors:

- Common Niche/Geographic Origin: Isolates from the same environmental sample (e.g., a soil core or plant tissue) are likely to have existing ecological interactions.

- Phylogenetic Relatedness or Distance: Pairing closely related species may induce defense-related metabolites, while pairing distantly related ones may simulate niche competition.

- Random Pairing: As a discovery tool, random pairing can yield unexpected results.

A generalized experimental workflow begins with cultivating fungal strains on solid agar media, typically on the same Petri dish but with a physical barrier (e.g., a central wall) to allow for initial independent growth. After a set period (e.g., 3-7 days), the barrier is removed, forcing the mycelia to interact. The interaction zone is then carefully monitored for morphological changes and pigmentation, which are often visual indicators of novel metabolite production [24]. For analytical purposes, the entire co-culture (including interaction zones and mono-culture areas) is extracted and compared chromatographically to monoculture extracts to identify co-culture-specific metabolites.

Cross-Kingdom Pairings (Fungal-Bacterial)

Cross-kingdom interactions are complex and can yield a rich array of outcomes, from antagonism to synergy. The nature of the interaction is highly dependent on the specific pairing and environmental conditions. A standardized protocol for initial screening involves cross-streak or dual-culture assays on solid agar [25] [28]. One microbe (e.g., a bacterium) is streaked in a line on the plate, and the other (e.g., a fungus) is streaked perpendicularly or point-inoculated at a set distance. After incubation, the growth inhibition or stimulation of each microbe is measured relative to its growth in monoculture. These interactions can be categorized as mutualism (both benefit), commensalism (one benefits, the other unaffected), amensalism (one harmed, the other unaffected), or antagonism (one harms the other) [28]. To investigate the chemical basis of the interaction, the co-culture can be grown in a liquid system, either in a fully mixed setup or physically separated by a membrane, followed by metabolomic profiling via LC-MS or GC-MS to identify induced compounds [25].

The diagram below illustrates the decision-making workflow for selecting microbial partners and the corresponding experimental setups.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful co-cultivation experiments rely on specialized reagents and equipment designed to facilitate microbial interactions while allowing for necessary separation and analysis.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Co-Culture Experiments

| Item | Function/Application | Specific Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid-Liquid Co-culture Vessel | Permits metabolite exchange between physically separated cultures. | UniWells Horizontal Co-Culture Plate used for isolating Waltera spp. with a 0.3 µm pore size filter [2]. |

| Low-Nutrient Media | Mimics oligotrophic natural environments, favoring cooperative interactions. | Use of diluted standard media (e.g., 10% strength) or specific oligotrophic base like YCFA for gut microbes [25] [2]. |

| Membrane Filters | (a) For physical separation in co-culture; (b) For size-selective isolation of target microbes. | (a) 0.1-0.3 µm filters for metabolite exchange. (b) 0.22-0.45 µm filters to obtain a "filtered bacterial solution" of small, difficult-to-culture cells [2]. |

| Anaerobic Chamber | Essential for cultivating obligate anaerobes from environments like the gut or sediments. | Cultivation under H₂/CO₂/N₂ (0.5:0.5:9) atmosphere at 37°C for human gut isolates [2]. |

Troubleshooting and Data Interpretation

Even with a well-considered pairing strategy, challenges in interpretation are common. A frequent observation is the absence of growth in the initial co-culture. In such cases, consider altering the nutrient richness of the medium, as high nutrient levels can promote antagonism over cooperation [25]. Varying the temporal sequence of inoculation (e.g., inoculating the supporting strain several days before the target) can also be critical, as it allows the helper microbe to establish and produce necessary growth factors [23]. If no induced metabolites are detected, increasing the physical proximity of the cultures or transitioning from a separated system to a mixed culture can intensify the interaction and stimulate biosynthesis [24].

When analyzing results, it is crucial to determine which partner in the co-culture is producing any novel metabolites of interest. This can be achieved by analyzing monoculture extracts of each partner separately and comparing their metabolic profiles to that of the co-culture extract via chromatographic techniques (e.g., HPLC, TLC) [24]. Furthermore, a lack of growth in the presence of a spent supernatant from the helper culture, contrasted with growth during active co-culture, strongly indicates a symbiotic relationship reliant on the continuous, bidirectional exchange of metabolites rather than a one-off provision of a growth factor [2]. This insight is vital for understanding the nature of the microbial interaction and for designing subsequent experiments.

Co-cultivation has emerged as a powerful methodology for researching difficult-to-culture microorganisms by mimicking their natural ecological niches. This approach leverages symbiotic interactions between microbial species to unlock growth and metabolic capabilities not observed in axenic cultures. The strategic selection of cultivation setup—spanning solid versus liquid media and small-scale versus bioreactor systems—represents a critical decision point that directly determines research outcomes. Within the broader thesis on co-cultivation techniques, this document provides detailed application notes and protocols for implementing these configurations, specifically focusing on their application for fastidious microorganisms that resist conventional cultivation methods.

The fundamental principle underpinning co-cultivation is that microbial interactions in mixed cultures can induce silent metabolic pathways and provide necessary growth factors through cross-feeding or signaling molecules. These interactions are profoundly influenced by the physical and chemical environment, which varies significantly between solid and liquid systems, and between different scales of operation. The protocols herein are designed to guide researchers in selecting and implementing the optimal configuration for their specific research objectives, whether aimed at isolating novel taxa, inducing specialized metabolite production, or producing consortia for therapeutic applications.

Comparative Analysis of Solid and Liquid Co-Cultivation Systems

Solid-State Co-Cultivation

Solid-state fermentation (SSF) involves cultivating microorganisms on a solid substrate with minimal free water, creating a heterogeneous environment that often mimics natural microbial habitats such as soil or surfaces. This system is particularly advantageous for filamentous fungi and other microorganisms that naturally colonize solid surfaces, as it supports their morphological development and spatial organization.

The industrial importance of SSF lies in its application for producing enzymes, industrial chemicals, bioactive secondary metabolites, and pharmaceutical products. The technique benefits from reduced energy consumption due to lower agitation requirements, minimal water usage, and decreased contamination risk. Furthermore, downstream processing is often more straightforward, with enzymes and metabolites present in concentrated forms that require less solvent for extraction [29].

Table 1: Solid vs. Liquid Media for Co-Cultivation

| Parameter | Solid Media (SSF) | Liquid Media (SmF) |

|---|---|---|

| Water Activity | Low (just enough for growth/metabolism) [29] | High (submerged culture) |

| Microbial Compatibility | Best for fungi and yeasts; some bacteria [29] | Broad (bacteria, yeast, microalgae) [2] [4] |

| Key Advantage | Concentrated products; cheap substrates; resistant to contaminants [29] | Better control of parameters; homogenous mixing; easier sampling [2] |

| Key Disadvantage | Difficulty in controlling parameters (e.g., moisture, heat) [29] | Requires higher energy for agitation/aeration [30] |

| Process Control | Difficult | Straightforward |

| Downstream Processing | Less expensive; lower recovery cost [29] | More complex |

| Ideal Application | Enzyme production; metabolic induction via synergistic degradation [29] | Isolation of difficult-to-culture bacteria; synthetic community construction [2] [4] |

Liquid-State Co-Cultivation

Liquid-liquid or submerged co-cultivation (SmF) occurs in an aqueous medium where microorganisms grow in a suspended, homogeneous environment. This system provides superior control over physicochemical parameters—including pH, dissolved oxygen, and nutrient concentrations—enabling precise manipulation of cultivation conditions. Liquid systems are indispensable for scalable production and quantitative studies requiring reproducible and uniform growth environments.

A particularly innovative application of liquid co-cultivation is the "liquid-liquid co-culture method" which utilizes specialized vessels separated by membrane filters. This configuration allows continuous metabolite exchange while maintaining physical separation between supporting bacteria and target difficult-to-culture isolates. This method has successfully isolated previously uncultivated species such as Waltera intestinalis and Waltera acetigignens from human gut samples [2] [31]. These bacteria exhibited unique growth characteristics, with cells being small and filterable in early culture stages but elongating significantly with prolonged incubation [31].

Liquid systems also facilitate the establishment of stable synthetic consortia through continuous cultivation. Recent research demonstrates that continuous co-culturing of nine anaerobic intestinal bacteria produced a consortium with compositional and metabolic equilibrium distinct from simple mixtures of individually cultured strains. This co-cultured consortium effectively recapitulated complete carbohydrate fermentation pathways and demonstrated therapeutic efficacy in a mouse colitis model matching that of fecal microbiota transplant [4].

Scale Considerations: Small-Scale vs. Bioreactor Systems

Small-Scale Cultivation

Small-scale systems, including microtiter plates, shake flasks, and specialized co-culture vessels, offer practical solutions for initial screening, method development, and isolation efforts. These systems require minimal resources, enable high-throughput experimentation, and provide flexible platforms for investigating diverse microbial partnerships.

The UniWells Horizontal Co-Culture Plate represents a specialized small-scale configuration particularly suited for isolating difficult-to-culture microorganisms. This system features compartments separated by membrane filters (typically 0.1-0.3 µm pore size) that permit metabolite exchange while maintaining physical separation between supporting and target microorganisms [2]. This setup created the essential conditions for isolating Waltera species, which failed to grow in agar-based co-culture systems, suggesting that continuous liquid-liquid metabolite exchange was critical for their cultivation [2].

Bioreactor Co-Cultivation

Bioreactors provide sophisticated control systems for monitoring and adjusting critical parameters including dissolved oxygen, pH, temperature, and feeding strategies during co-cultivation. These systems enable researchers to study microbial interactions under defined and reproducible conditions while collecting rich datasets on process kinetics.

Table 2: Small-Scale vs. Bioreactor Co-Cultivation

| Parameter | Small-Scale (e.g., Shake Flasks, Plates) | Bioreactor |

|---|---|---|

| Volume Range | < 100 mL [32] | 0.5 - 5,000 L [32] |

| Process Control | Limited (temperature, shaking speed) | Comprehensive (DO, pH, feeding) [33] [32] |

| Mixing Efficiency | Variable; depends on shaking | Controlled and reproducible agitation [32] |

| KPI Impact | Baseline performance | Can reduce yield by >20% due to gradients [34] |

| Homogeneity | Generally good at very small scales | Gradients of DO, pH, and substrates likely [34] [32] |

| Scale-Up Potential | Low | Directly translatable |

| Primary Use | Screening, isolation, initial optimization [2] | Process characterization, mass production [33] |

| Cost & Complexity | Low | High |

Scale-up from laboratory to production scale introduces significant challenges, primarily related to gradient formation in large vessels. As bioreactor volume increases, mixing times extend from seconds to minutes, creating heterogeneous environments with spatial and temporal variations in substrate concentration, dissolved oxygen, and pH [34] [32]. Cells circulating through these varying microenvironments experience fluctuating conditions that can trigger metabolic adaptations, potentially leading to reduced biomass yield, altered product profiles, and byproduct formation [34].

In co-cultivation specifically, these gradients can disproportionately affect interacting microbial partners. Research with Aspergillus terreus and Streptomyces rimosus demonstrated that the timing of co-culture initiation and medium composition significantly influenced which strain dominated the system and consequently shaped the secondary metabolite profile [33]. Monitoring dissolved oxygen levels served as a valuable indicator for identifying the dominant microorganism during the process [33].

Application Notes and Protocols

Protocol 1: Liquid-Liquid Co-Culture for Isolating Difficult-to-Culture Bacteria

This protocol describes the isolation of difficult-to-culture bacteria from human gut samples using the liquid-liquid co-culture method, which successfully isolated Waltera and Roseburia species [2].

Experimental Workflow:

Detailed Methodology:

Sample Preparation:

- Obtain fresh fecal sample from healthy donor with informed consent.

- Suspend 0.5 g sample in 4.5 ml phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

- Degas by flushing with nitrogen gas to establish anaerobic conditions.

- Prepare 10⁻³ dilution in PBS.

- Filter a portion of the diluted sample through a 0.45 µm pore-size membrane filter to obtain a "filtered bacterial solution" containing small, difficult-to-culture bacteria [2].

Co-culture Setup:

- Use a horizontal co-culture vessel (e.g., UniWells Horizontal Co-Culture Plate).

- Add 1,450 µl of YCFA medium (or other suitable anaerobic medium like mGAM) to each well.

- Inoculate one side of the co-culture vessel with 50 µl of the diluted fecal sample to serve as supporting bacteria (SB).

- Inoculate the opposite side with 50 µl of the filtered bacterial solution.

- Insert a membrane filter (0.3 µm pore size) between the co-culture vessels to allow metabolite exchange while maintaining physical separation [2].

- Include control with monoculture of filtered bacterial solution.

Incubation:

- Place the co-culture vessel in an anaerobic chamber.

- Maintain at 37°C under H₂/CO₂/N₂ atmosphere (volume ratio: 0.5:0.5:9) for 2 days [2].

Subculturing and Isolation:

- After incubation, transfer 100 µl from the filtered bacterial solution side onto various agar media.

- Incubate plates for 2 days under anaerobic conditions.

- Isolate individual colonies and purify through repeated streaking [2].

Identification:

- Extract genomic DNA from pure cultures.

- Amplify 16S rRNA gene using primers 27F and 1492R.

- Sequence PCR products and perform homology search using databases like EzBioCloud for taxonomic identification [2].

Troubleshooting Notes:

- If no growth occurs in co-culture, test different pore-size membranes (0.1-0.3 µm) or alternative supporting bacteria.

- If contamination occurs, ensure proper anaerobic techniques and filter sterilization of media.

- For strains that do not grow after initial isolation, maintain through continuous liquid-liquid co-culture with supporting bacteria.

Protocol 2: Bioreactor Co-Cultivation for Secondary Metabolite Induction

This protocol describes the bioreactor co-cultivation of Aspergillus terreus and Streptomyces rimosus to induce novel secondary metabolite production, representing a model "microbial war" scenario [33].

Experimental Workflow:

Detailed Methodology:

Strain Preparation and Preculture:

- Maintain Aspergillus terreus ATCC 20542 and Streptomyces rimosus ATCC 10970 on agar slants according to ATCC recommendations.

- Prepare precultures in appropriate liquid media (e.g., 300 ml volume) to generate active inoculum [33].

Bioreactor Setup and Sterilization:

- Use stirred-tank bioreactors (e.g., BIOSTAT B) with 5.5 L initial working volume.

- Calibrate dissolved oxygen (DO) and pH probes before sterilization.

- Sterilize bioreactor with medium in situ or use sterile single-use bioreactors.

- Set temperature control to 28-30°C as appropriate for the strains [33].

Inoculation Strategy:

- Employ one of three co-culture initiation approaches:

- Simultaneous inoculation: Co-inoculate both strains at time zero.

- Staggered inoculation A: Inoculate S. rimosus into an already established bioreactor culture of A. terreus.

- Staggered inoculation B: Inoculate A. terreus into an already established bioreactor culture of S. rimosus [33].

- Include parallel monoculture controls for both strains.

- Employ one of three co-culture initiation approaches:

Process Monitoring and Control:

- Maintain dissolved oxygen level at 20% saturation by automatic adjustment of air flow rate (1.5-5.5 L·min⁻¹) and stirring speed (220-300 min⁻¹).

- Monitor biomass growth, substrate consumption, and pH throughout cultivation.

- Collect samples at regular intervals (e.g., every 12-24 h) for metabolite analysis and microscopic observation [33].

Metabolite Analysis:

- Extract metabolites from culture broth using appropriate solvents.

- Analyze extracts by liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS).

- Compare metabolic profiles of co-cultures with monoculture controls to identify novel metabolites induced by microbial interactions [33].

Technical Notes:

- The inoculation strategy significantly influences which strain dominates the co-culture and consequently shapes the metabolic profile.

- S. rimosus typically dominates over A. terreus unless introduced into an already established A. terreus culture [33].

- Dissolved oxygen dynamics serve as a valuable real-time indicator of microbial competition and dominance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Co-Cultivation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| YCFA Medium | Defined medium for cultivating anaerobic gut bacteria [2] | Isolation of Waltera and Roseburia species from fecal samples [2] |

| UniWells Horizontal Co-Culture Plate | Specialized vessel for liquid-liquid co-culture with metabolite exchange [2] | Physical separation of supporting and target bacteria while allowing chemical communication [2] |

| Membrane Filters (0.1-0.3 µm) | Size-based separation of microbial cells and metabolite exchange [2] | Selecting small-sized bacteria; separating co-culture compartments [2] |

| Anaerobic Chamber (H₂/CO₂/N₂) | Creates oxygen-free environment for strict anaerobes [2] | Cultivation of oxygen-sensitive gut microorganisms [2] [4] |

| mGAM Medium | General anaerobic medium for fastidious microorganisms [2] | Alternative medium for gut microbiome studies [2] |

| Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) | Models gradient formation in large-scale bioreactors [34] | Predicting substrate, DO, and pH gradients during scale-up [34] |

The strategic selection of cultivation configuration—encompassing both media physical state and system scale—profoundly influences the success of co-cultivation approaches for difficult-to-culture microorganisms. Solid-state systems provide naturalistic environments that frequently enhance metabolic productivity and stability for filamentous fungi, while liquid systems enable precise control and have proven invaluable for isolating previously uncultivated bacterial species through continuous metabolite exchange. Small-scale setups offer practical solutions for isolation and screening, whereas bioreactors facilitate process characterization and scale-up, albeit with the challenge of managing heterogeneous environments.