Unrecognized Human Bacterial Pathogens: Detection Challenges and Innovative Therapeutic Strategies

This article addresses the critical and growing challenge of unrecognized and drug-resistant bacterial pathogens, a pressing concern for global public health.

Unrecognized Human Bacterial Pathogens: Detection Challenges and Innovative Therapeutic Strategies

Abstract

This article addresses the critical and growing challenge of unrecognized and drug-resistant bacterial pathogens, a pressing concern for global public health. It explores the foundational science behind their emergence, including the alarming rise of 'nightmare bacteria' like NDM-producing strains. The scope extends to advanced methodological approaches for pathogen identification, such as metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) and the Tm mapping method. It further investigates the significant hurdles in developing novel therapeutics against these pathogens, analyzing the dwindling antibiotic pipeline and the promise of targeted strategies like narrow-spectrum agents and drug repurposing. Finally, the article provides a comparative validation of emerging diagnostic technologies against traditional culture, offering a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals navigating this complex field.

The Rising Tide of Stealth Pathogens: Understanding the Scale and Mechanisms of Resistance

The escalating crisis of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) represents a quintessential silent pandemic, undermining decades of progress in infectious disease control. AMR is projected to cause 10 million deaths annually by 2050 if left unaddressed, posing a severe threat to global health and modern medicine [1]. This technical brief examines the convergence of two critical fronts in this battle: the rapid emergence of pan-resistant "nightmare bacteria" and the elusive reservoir of asymptomatic human carriers who facilitate their spread. Within the context of unrecognized human bacterial pathogens research, this dynamic creates a perfect storm for stealth transmission, challenging conventional detection paradigms and therapeutic development. The intricate interplay between bacterial evolution, host-pathogen interactions, and diagnostic limitations necessitates a fundamental re-evaluation of our approaches to pathogen surveillance and containment.

The Expanding Spectrum of Resistant Pathogens

Quantitative Landscape of Resistance

Surveillance data reveal an alarming acceleration in resistance mechanisms, particularly among Gram-negative pathogens. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that infection rates from drug-resistant "nightmare bacteria" rose almost 70% between 2019 and 2023 [2]. The rate of infections caused by bacteria carrying the New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase (NDM) gene, which confers resistance to nearly all beta-lactam antibiotics including carbapenems, rose more than fivefold (460%) during this period [2]. This is particularly concerning as NDM-carrying pathogens are susceptible to only two remaining antibiotics, both of which are expensive and require intravenous administration [2].

Table 1: Emerging High-Priority Resistant Pathogens and Their Mechanisms

| Pathogen | Resistance Mechanism | Key Genetic Determinants | Therapeutic Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Carbapenem resistance | blaKPC, blaNDM, blaOXA-48 | Limited to aminoglycosides, tigecycline, fosfomycin, colistin |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | Multi-drug resistance | OXA-type carbapenemases, efflux pumps, porin mutations | Polymyxins remain last resort |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Efflux pumps, enzymatic degradation | MexAB-OprM, blaCTX-M, blaVIM | Compounded resistance challenges in immunocompromised |

| Escherichia coli | Extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBL) | blaCTX-M, blaTEM, blaSHV | Rising resistance to fluoroquinolones |

| Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) | Altered drug target | mecA (PBP2a) | Resistance to all β-lactams |

The molecular mechanisms driving this crisis are diverse and continuously evolving. Traditional resistance pathways include three dominant strategies: (1) target site modification (e.g., PBP2a in MRSA), (2) enzymatic degradation (e.g., β-lactamases), and (3) reduced drug accumulation via efflux pumps or membrane permeability barriers [1]. The horizontal gene transfer of resistance determinants via plasmids, transposons, and integrons further accelerates the dissemination of these traits across microbial populations [1].

The Carrier Conundrum in Disease Transmission

Asymptomatic carriers—individuals who host pathogenic organisms without displaying clinical symptoms—represent a critical blind spot in AMR containment. Mathematical models indicate that the presence of asymptomatic carriers significantly complicates disease control by undermining interventions that rely on identifying symptomatic cases [3]. For pathogens like Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae, carriers can unknowingly transmit resistant strains while remaining undetected by conventional surveillance systems [3].

The epidemiological significance of asymptomatic carriage is profound. Current models suggest that interventions targeting only symptomatically infected hosts while ignoring asymptomatic carriers are often incapable of achieving disease control, even when multiple intervention strategies are implemented simultaneously [3]. This is particularly relevant for AMR, where asymptomatic carriage may exert selective pressure that contributes to the emergence and transmission of drug-resistant strains when carriers are unknowingly treated with antibiotics [3].

Table 2: Documentated Prevalence of Asymptomatic Carriage for Key Pathogens

| Pathogen | Carriage Prevalence | Population Context | Implications for AMR Spread |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neisseria meningitidis | 10-35% | Young adults | Approaching 100% in closed populations |

| Influenza virus | 5-35% | General population | Pre-symptomatic transmission undermines control |

| Salmonella enterica ser. Typhi | 1-6% | Post-infection | Chronic carriage (exemplified by "Typhoid Mary") |

| Ebola virus | 27-71% | During outbreaks | Significant proportion never develop symptoms |

| Clostridioides difficile | >50% | Long-term care patients | Extended fecal contamination despite lack of symptoms |

Diagnostic Challenges and Methodological Advances

Limitations of Conventional Detection Paradigms

Traditional culture-based methods for bacterial identification, while inexpensive and conceptually simple, require 2-3 days for preliminary identification and more than a week for species confirmation [4]. These approaches suffer from critical limitations in sensitivity, particularly for detecting viable but non-culturable (VBNC) pathogens that may lead to false-negative results [4]. Furthermore, standard biochemical tests often fail to distinguish between closely related species with dramatically different pathogenic profiles and resistance patterns [5] [6].

The clinical implications of these diagnostic shortcomings are substantial. In cases where Escherichia marmotae is mistaken for E. coli, for instance, inappropriate broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy may be administered, exerting unnecessary selective pressure for resistance development [6]. Such misidentification underscores the critical need for species-specific diagnostic methods that can guide targeted therapeutic interventions.

Advanced Molecular Detection Platforms

Nucleic acid-based detection methods have emerged as powerful alternatives to conventional culture-based techniques. These platforms offer superior sensitivity, specificity, and rapid turnaround times, enabling pathogen-directed therapy within clinically relevant timeframes [4].

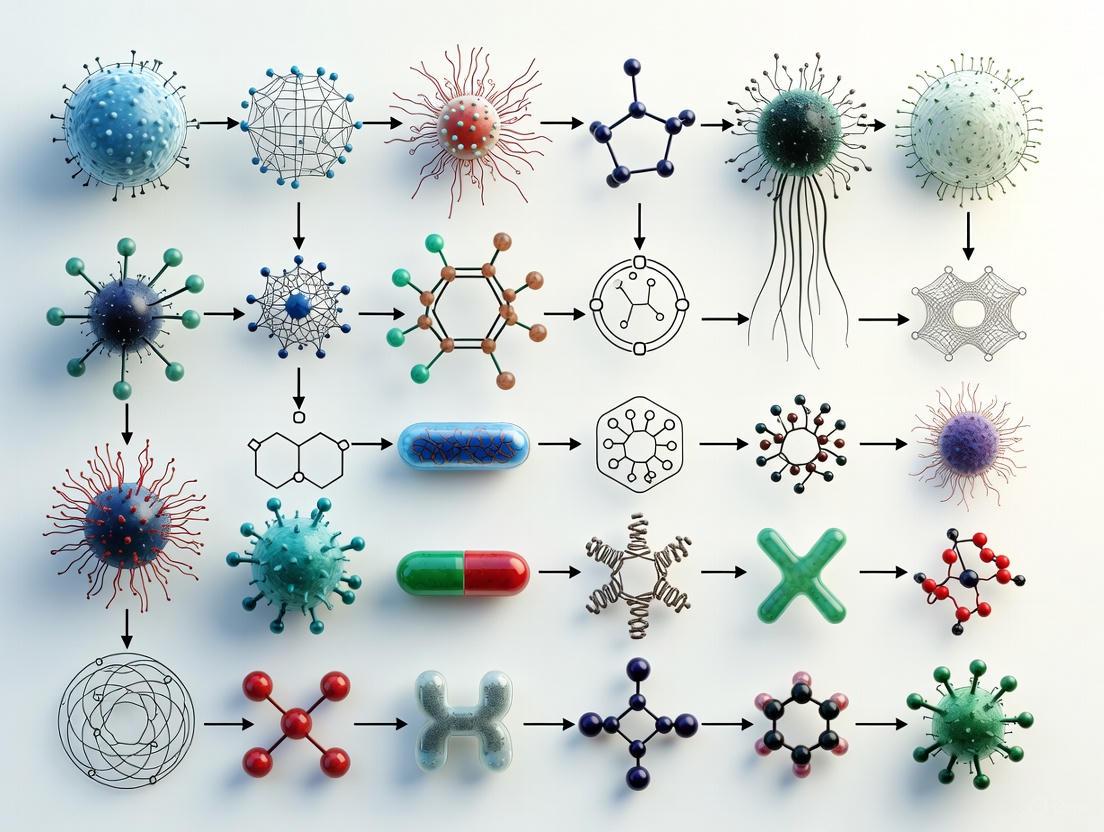

Diagram 1: Molecular Detection Workflow

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and its variants form the cornerstone of modern molecular detection. Simple PCR allows detection of a single bacterial pathogen by amplifying a specific target DNA sequence, while multiplex PCR (mPCR) enables simultaneous amplification of multiple gene targets, offering a more comprehensive approach to pathogen identification [4]. Real-time PCR (qPCR) provides both detection and quantification of target organisms, making it particularly valuable for surveillance applications [7].

Isothermal amplification techniques such as loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) and nucleic acid sequence-based amplification (NASBA) offer advantages in resource-limited settings by eliminating the need for thermal cyclers [4]. For complex samples containing multiple potential pathogens, oligonucleotide DNA microarrays facilitate high-throughput screening of numerous genetic targets simultaneously [4].

Novel Surveillance Approaches and Emerging Platforms

Innovative surveillance strategies are leveraging molecular techniques to monitor resistance spread. The CDC's Active Bacterial Core surveillance (ABCs) program employs laboratory- and population-based surveillance to monitor invasive bacterial infections that cause bloodstream infections, sepsis, and meningitis [8]. This system provides critical data on emerging resistance patterns and informs vaccine and public health policies.

Recent research has identified novel bacterial immune systems that may inspire future diagnostic platforms. The Panoptes system, discovered in bacteria, operates by sensing viral interference with cellular signals and launching a counterattack [9]. This sophisticated mechanism for detecting pathogen intrusion demonstrates the potential for borrowing biological recognition elements from natural systems to develop novel detection technologies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Core Reagent Solutions for AMR Research

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Antimicrobial Resistance Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromogenic/Fluorogenic Enzyme Substrates | Nitrocefin, X-Gluc, FDG | Detection of β-lactamase activity; bacterial enumeration | Visual detection of specific enzyme activities via color/fluorescence change |

| PCR Reagents | Specific primers (e.g., for mecA, blaNDM), dNTPs, thermostable DNA polymerase | Molecular detection of resistance genes | Amplification of specific DNA sequences for pathogen identification |

| Culture Media | Selective agars (e.g., CHROMagar, MRSA Select) | Isolation and presumptive identification of resistant pathogens | Support growth of target organisms while inhibiting competitors; color-based differentiation |

| Antibiotic Test Panels | Broth microdilution panels, Etest strips | Determination of minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) | Quantitative assessment of antibiotic susceptibility |

| Whole Genome Sequencing Kits | Library preparation reagents, sequencing adapters | Comprehensive analysis of resistance genes and mobile genetic elements | High-resolution characterization of resistance determinants |

Experimental Protocol: Molecular Detection of NDM-Producing Enterobacteriaceae

Principle: This protocol describes a real-time PCR (qPCR) method for detecting the blaNDM gene in clinical isolates or directly from surveillance samples, enabling rapid identification of carbapenem-resistant organisms.

Sample Preparation:

- For bacterial isolates: Inoculate 3-5 colonies into 200μL of nuclease-free water and heat at 95°C for 10 minutes. Centrifuge at 12,000 × g for 2 minutes, and use supernatant as template.

- For direct specimen testing: Extract nucleic acids using a commercial kit with optional DNase treatment if RNA detection is required.

qPCR Reaction Setup:

- Prepare master mix containing:

- 10μL of 2× qPCR master mix

- 1μL of forward primer (10μM): 5'-GGGCAGTCGCTTCCAACGGT-3'

- 1μL of reverse primer (10μM): 5'-GTAGTGCTCAGTGTCGGCAT-3'

- 0.5μL of probe (10μM): 5'-[FAM]ACTCGCAAGACTGCTACCC-[BHQ1]-3'

- 2.5μL of nuclease-free water

- Add 5μL of template DNA to 15μL of master mix

- Include positive control (plasmid with blaNDM insert) and negative control (nuclease-free water)

Amplification Parameters:

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 3 minutes

- 40 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15 seconds

- Annealing/Extension: 60°C for 60 seconds (collect fluorescence)

- Analysis: Determine Cq values with threshold set in exponential phase of amplification

Interpretation: Cq values ≤35 indicate presence of blaNDM gene. Confirm positive results with melting curve analysis if using SYBR Green chemistry.

Conceptual Framework for Pathogen Emergence and Detection

The complex interplay between bacterial evolution, transmission dynamics, and detection capabilities can be visualized as a cyclical process that drives the silent spread of resistant pathogens.

Diagram 2: AMR Transmission Cycle

This framework illustrates how diagnostic limitations perpetuate a cycle of resistance amplification. Asymptomatic carriers facilitate silent transmission, while diagnostic gaps enable continued spread until treatment failures trigger recognition of the problem. Each iteration of this cycle expands the reservoir of resistant organisms and further complicates containment efforts.

The convergence of expanding resistance mechanisms and widespread asymptomatic carriage represents a critical challenge in microbial pathogenesis research. The silent transmission of resistant pathogens through unrecognized carriers underscores the urgent need for innovative detection technologies that can identify both the pathogens and their resistance determinants within clinically relevant timeframes.

Future research directions must include the development of point-of-care diagnostic platforms that integrate multiplexed detection of pathogens and their resistance profiles, enabling targeted therapy while minimizing unnecessary antibiotic exposure. Furthermore, a deeper understanding of the host-pathogen interactions that permit asymptomatic carriage may reveal novel therapeutic targets for disrupting transmission networks.

The escalating threat of nightmare bacteria necessitates a paradigm shift in our approach to resistance containment—from reactive treatment to proactive detection and interruption of transmission chains. By leveraging advanced molecular technologies and embracing comprehensive surveillance strategies, the scientific community can mount a more effective defense against this invisible pandemic.

The relentless evolution of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) represents one of the most pressing challenges in modern medicine, particularly with the emergence and global spread of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE). Among these, New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase-producing CRE (NDM-CRE) constitutes a critical threat due to their extensive resistance profiles and association with severe morbidity and mortality. Recent epidemiological data from the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reveals a disturbing trend: between 2019 and 2023, NDM-CRE infections surged by approximately 460% in the United States [10] [11] [12]. This unprecedented increase has transformed NDM-CRE from a historically uncommon pathogen in the U.S. into a predominant clinical concern, with incidence rates now comparable to the previously dominant Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC) variants [13].

This whitepaper contextualizes the dramatic rise of NDM-CRE within the broader framework of unrecognized human bacterial pathogens research. We present a comprehensive technical analysis of the epidemiological landscape, molecular mechanisms of resistance, detection methodologies, and therapeutic challenges associated with NDM-CRE. The objective is to provide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with an integrated resource that bridges surveillance data with experimental and clinical insights, ultimately guiding future research priorities and intervention strategies against these formidable pathogens.

Epidemiological Landscape: Quantifying the Surge

Data compiled through the CDC's Antimicrobial Resistance Laboratory Network from 2019 to 2023 demonstrates a sharp upward trajectory in carbapenemase-producing CRE (CP-CRE), primarily fueled by the rise of NDM-producing strains. The following table summarizes the key quantitative findings from the recent CDC report published in the Annals of Internal Medicine [10] [13].

Table 1: Trends in Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales in the United States (2019-2023)

| Metric | 2019-2023 Change | Key Statistics & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Overall CP-CRE Incidence | Increased by 69% | Age-adjusted incidence rate ratio (aIRR) = 1.69 (95% CI, 1.61-1.78) [13]. |

| NDM-CRE Incidence | Increased by ~460% | Age-adjusted incidence rate ratio (aIRR) = 5.61 (95% CI, 4.96-6.36). This was the steepest increase among all carbapenemases [13]. |

| OXA-48-like-CRE Incidence | Increased by 5% | Age-adjusted incidence rate ratio (aIRR) = 1.5 (95% CI, 1.17-1.94) [13]. |

| KPC-CRE Incidence | Not specified in data | By 2023, NDM-CRE incidence became similar to KPC-CRE, previously the most common type in the U.S. [13]. |

| Historical Burden (2020) | ~12,700 CRE infections, ~1,100 deaths | From CDC's 2022 special report, provided for context on overall CRE impact [10] [14]. |

| Common NDM-CRE Infections | Pneumonia, bloodstream, urinary tract, wound infections | Infections are extremely difficult to treat and associated with high morbidity and mortality [10]. |

This surveillance data, representing 35% of the U.S. population, likely underestimates the true burden due to the absence of several high-population states and incomplete carbapenemase testing in many clinical laboratories [11] [13]. The rise of NDM-CRE is not isolated to the U.S.; it is part of a global phenomenon. A 2025 study by the Global Antibiotic Research & Development Partnership (GARDP) highlighted critical treatment gaps in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where only 6.9% of patients with drug-resistant Gram-negative infections received appropriate antibiotics [15].

The Pathogen: Biochemical and Genetic Mechanisms of NDM-CRE

Classification and Enzyme Function

NDM (New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase) is a transferable molecular class B metallo-β-lactamase (MβL). Unlike class A, C, and D β-lactamases that utilize a serine residue in their active site, class B enzymes are zinc-dependent metalloenzymes [16] [17]. The "metallo-" designation refers to the requirement for one or two zinc ions (Zn²⁺) in the active site to hydrolyze the β-lactam ring [16]. The gene encoding the most common variant, blaNDM-1, was first identified in 2008 in a Klebsiella pneumoniae isolate from a Swedish patient previously hospitalized in New Delhi, India [17].

NDM enzymes confer resistance by efficiently hydrolyzing a broad spectrum of β-lactam antibiotics. Their activity profile encompasses:

- Penicillins

- Cephalosporins

- Carbapenems (meropenem, imipenem, ertapenem)

Notably, NDM enzymes are not active against the monobactam aztreonam [17]. However, this intrinsic susceptibility is often negated in clinical isolates because NDM-producing organisms frequently co-harbor other resistance mechanisms, such as extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs), which hydrolyze aztreonam [16] [18].

Genetic Architecture and Horizontal Transfer

The rapid global dissemination of NDM is largely facilitated by its location on mobile genetic elements, particularly plasmids [16] [18] [17]. The blaNDM gene is often embedded within a complex genetic environment flanked by insertion sequences (IS), such as ISAba125, which contribute to its mobilization and expression [17] [19].

Table 2: Key Genetic and Biochemical Features of NDM Carbapenemases

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Ambler Class | Class B (Metallo-β-lactamase, MβL) [16] [17]. |

| Active Site | Zinc-dependent hydrolase (subclasses B1/B3: two Zn²⁺ ions; B2: one Zn²⁺ ion) [16]. |

| Genetic Location | Plasmid-borne, facilitating horizontal gene transfer [18] [17]. |

| Common Flanking Elements | Insertion sequences (e.g., ISAba125, IS5, IS26) [17] [19]. |

| Primary Hydrolysis Spectrum | Penicillins, Cephalosporins, Carbapenems [17]. |

| Notable Exception | No hydrolysis of Aztreonam (a monobactam) [17]. |

| Inhibitor Susceptibility | Resistant to all commercially available β-lactamase inhibitors (e.g., clavulanic acid, avibactam) [16] [17]. |

This genetic mobility allows blaNDM to spread not only among clinical strains of K. pneumoniae and E. coli but also across other members of the Enterobacterales order, and even into environmental bacteria, creating vast reservoirs of resistance [17] [19].

The following diagram illustrates the core genetic structure surrounding the blaNDM gene and its role in the primary resistance mechanism.

Detection and Diagnostic Challenges

A critical factor contributing to the silent spread of NDM-CRE is the widespread lack of routine carbapenemase testing in clinical laboratories [10] [11]. Many labs confirm carbapenem resistance but do not perform specific tests to identify the presence of a carbapenemase, much less differentiate its type. This diagnostic gap has significant clinical consequences:

- Delayed Targeted Therapy: Without knowing the carbapenemase type (e.g., NDM vs. KPC), clinicians may select initially ineffective antibiotics [10].

- Missed Opportunities for Infection Control: Failure to rapidly identify NDM-CRE carriers impedes the timely implementation of contact precautions to prevent transmission [10] [14].

Recommended Testing Methodologies

The CDC urges prompt carbapenemase testing whenever a CRE infection is identified [10]. The following table outlines key methods used in identification and their applications in both research and clinical settings.

Table 3: Diagnostic and Research Methods for NDM-CRE Detection

| Method Category | Examples & Specific Techniques | Primary Application & Function |

|---|---|---|

| Phenotypic Detection | CARBA NP test (colorimetric) [16].mSuperCARBA agar (chromogenic) [19].Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing (AST) with MIC determination [19]. | Rapid, functional confirmation of carbapenemase production.Screening and selective isolation of presumptive CP-CRE from complex samples (e.g., wastewater, clinical specimens). |

| Genotypic Detection | PCR for major carbapenemase genes (e.g., blaNDM, blaKPC, blaVIM, blaOXA-48) [19].Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS) (e.g., PacBio, Illumina) [19]. | Gold-standard for identifying specific carbapenemase genes.Comprehensive analysis of resistance genes, plasmid structures, virulence factors, and strain typing (MLST). |

| Public Health Support | Testing through public health laboratories (e.g., CDC's Antimicrobial Resistance Laboratory Network) [10]. | Confirmatory testing and surveillance when clinical labs lack capacity. |

The experimental workflow for the surveillance and characterization of NDM-CRE, as used in research settings, is summarized below. This workflow integrates both phenotypic and genotypic methods to fully understand the pathogen's properties and spread.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Research into NDM-CRE relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools to isolate, identify, and characterize these pathogens. The following table details key materials essential for experimental work in this field.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for NDM-CRE Investigation

| Research Reagent / Material | Function & Application in NDM-CRE Research |

|---|---|

| Chromogenic Agar (e.g., mSuperCARBA) | Selective isolation of presumptive carbapenemase-producing organisms from complex samples like clinical specimens or wastewater. Contains chromogenic substrates that produce colored colonies upon enzyme activity [19]. |

| Cation-Adjusted Mueller-Hinton Broth (CAMHB) | The standard medium for performing antibiotic susceptibility testing (AST), including minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) determinations, following CLSI guidelines [19]. |

| PCR Reagents & Primers | Specific primers for carbapenemase genes (blaNDM, blaKPC, blaVIM, blaOXA-48) are used for rapid genotypic screening and confirmation [19]. |

| Whole-Genome Sequencing Kits | Reagents for next-generation sequencing platforms (e.g., PacBio, Illumina) enable comprehensive genomic analysis, including strain typing, plasmid epidemiology, and resistance gene detection [19]. |

| Antibiotic Disks/Powders | Standardized antibiotics for AST and MIC testing are crucial for defining resistance profiles and evaluating the efficacy of new therapeutic compounds [19]. |

Therapeutic Landscape and Future Directions

The treatment of NDM-CRE infections is severely constrained because NDM enzymes are not inhibited by any currently marketed β-lactamase inhibitors [16]. While ceftazidime-avibactam is effective against class A KPC enzymes, it is inactive against class B metallo-β-lactamases like NDM [16] [18]. This leaves clinicians with a limited arsenal, often relying on older, more toxic antibiotics such as polymyxins (e.g., colistin), tigecycline, and fosfomycin [18] [17]. However, efficacy is variable, and these agents often fail in serious infections like bacteremia and pneumonia [18].

The pipeline for novel agents active against NDM is a critical area of development. Promising strategies include:

- Novel β-Lactamase Inhibitors: Compounds like xeruborbactam (a bicyclic boronate) are in clinical development and show promise as pan-β-lactamase inhibitors, including activity against NDM and other metallo-β-lactamases [16].

- Siderophore-Antibiotic Conjugates: These constructs, such as cefiderocol, exploit bacterial iron uptake systems to enhance antibiotic penetration into the cell, showing activity against some NDM-producing strains [16] [18].

- Combination Therapies: Rational combinations of existing antibiotics, sometimes including aztreonam to exploit the "Achilles' heel" of NDM, are being explored to overcome resistance [18] [17].

Beyond drug development, strengthening infection prevention and control (IPC) measures in healthcare settings is paramount to curbing the spread of NDM-CRE. The CDC emphasizes consistent hand hygiene, wearing gloves and gowns during patient care (Contact Precautions), and rigorous environmental cleaning and disinfection [10] [13]. Furthermore, enhancing surveillance and diagnostic capacity to enable rapid detection and implementation of these precautions is a foundational component of any public health response to this growing threat [10] [11].

The 460% surge in NDM-CRE infections over a mere four-year period is a stark warning of the rapid evolution and dissemination of unrecognized bacterial pathogens. This whitepaper has delineated the multifaceted nature of the NDM-CRE threat, integrating quantitative epidemiology, molecular genetics, diagnostic challenges, and therapeutic limitations. The rise of NDM-CRE underscores the critical importance of a "One Health" approach, recognizing the interconnectedness of human health, animal health, and the environment in the spread of resistance genes [16] [19].

For the research community, the path forward demands a concerted effort on several fronts: (1) the development and deployment of rapid, accessible diagnostic tests to distinguish carbapenemase types; (2) accelerated discovery of novel therapeutic agents, particularly broad-spectrum β-lactamase inhibitors effective against metallo-enzymes; and (3) enhanced genomic surveillance to track the evolution and spread of high-risk NDM-CRE clones and plasmids. Addressing the NDM-CRE crisis requires a synergistic effort between basic researchers, clinical scientists, public health agencies, and drug developers to prevent a regression to the pre-antibiotic era for an increasing number of patients.

The relentless evolution of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) represents one of the most pressing challenges to modern medicine and public health. Within the broader context of unrecognized human bacterial pathogens research, understanding the drivers of resistance is paramount for developing effective countermeasures. The World Health Organization identifies bacterial AMR as directly responsible for 1.27 million global deaths annually and a contributing factor to 4.95 million deaths, underscoring the scale of this crisis [20]. The complex interplay between antibiotic misuse, horizontal gene transfer mechanisms, and disruptive global events like the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the emergence and dissemination of resistant pathogens. This whitepaper provides a technical examination of these core drivers, offering researchers and drug development professionals a comprehensive analysis of the mechanisms, transmission pathways, and methodologies essential for combating AMR. The pandemic undid years of progress, with U.S. hospitals witnessing significant increases in healthcare-associated, antimicrobial-resistant infections [21]. As we explore the molecular machinery of resistance dissemination and the quantitative assessment of antimicrobial use, this review aims to equip the scientific community with the knowledge and tools necessary to address this escalating threat through enhanced surveillance, stewardship, and innovative research approaches.

Antibiotic Misuse and Selective Pressure

Mechanisms of Antimicrobial Action and Resistance

Antimicrobial agents target essential bacterial cellular processes through distinct mechanisms of action, which corresponding resistance mechanisms have evolved to counteract. Table 1 summarizes the primary antibiotic classes, their cellular targets, and the resistance strategies employed by bacterial pathogens.

Table 1: Antimicrobial Mechanisms of Action and Corresponding Bacterial Resistance Strategies

| Mechanism of Action | Antimicrobial Classes | Primary Resistance Mechanisms | Example Pathogens with Intrinsic Resistance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibit Cell Wall Synthesis | β-Lactams, Carbapenems, Cephalosporins, Penicillins, Glycopeptides | Drug inactivation (e.g., β-lactamases), Target modification, Reduced permeability | Enterococci (cephalosporins), Listeria monocytogenes (cephalosporins) [22] |

| Depolarize Cell Membrane | Lipopeptides | Membrane modification, Efflux pumps | All Gram-negative bacteria (lipopeptides) [22] |

| Inhibit Protein Synthesis | Aminoglycosides, Tetracyclines, Macrolides, Chloramphenicol | rRNA methylation, Efflux pumps, Enzymatic modification | Bacteroides spp. (aminoglycosides), E. coli (macrolides) [22] |

| Inhibit Nucleic Acid Synthesis | Quinolones, Fluoroquinolones | Target mutations (gyrase, topoisomerase), Efflux pumps | Serratia marcescens (macrolides) [22] |

| Inhibit Metabolic Pathways | Sulfonamides, Trimethoprim | Bypass pathways, Target enzyme mutations | Pseudomonas aeruginosa (sulfonamides) [22] |

The improper stewardship of antimicrobial agents, including increased consumption in humans and animals, along with inappropriate prescribing practices, has created selective pressure that favors resistant organisms [22]. Patients with the highest exposure to antimicrobials are at greatest risk for infection with drug-resistant bacteria, creating a vicious cycle of escalating resistance [22].

Quantitative Evaluation of Antimicrobial Use

Accurate assessment of antimicrobial use patterns is fundamental to antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs). Quantitative evaluation employs standardized metrics to measure the volume and frequency of antimicrobial consumption, enabling correlation with resistance development and assessment of intervention effectiveness [23].

Table 2: Core Metrics for Quantitative Evaluation of Antimicrobial Use

| Metric | Definition | Calculation Method | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Defined Daily Dose (DDD) | The average maintenance daily dose for adults using a specific antimicrobial for its primary indication [23] | (Total antimicrobial weight in grams) / (Standard DDD value) | Easy data collection (no patient-specific data needed), Applicable to children | Not applicable to pediatric populations, Inaccurate with renal impairment or combination therapy |

| Days of Therapy (DOT) | The sum of the number of days each patient receives antimicrobial therapy, regardless of dose [23] | Count of days each antimicrobial agent was administered to a patient | More intuitive than DDD, Better reflects actual exposure | Requires patient-specific data, Labor-intensive to collect |

| Standardized Antimicrobial Administration Ratio (SAAR) | A risk-adjusted benchmark comparing observed versus predicted antimicrobial use [23] | Complex statistical modeling based on patient demographics and facility factors | Allows comparison between facilities, Adjusts for case mix | Requires sophisticated data infrastructure and analysis |

The WHO Access, Watch, and Reserve (AWaRe) classification system further supports antimicrobial use evaluation by categorizing drugs based on their potential to develop resistance. "Access" group antibiotics feature narrow spectra and good safety profiles, "Watch" agents have broader spectra and higher resistance potential, while "Reserve" antibiotics are last-resort options for multidrug-resistant infections [23].

Horizontal Gene Transfer: The Molecular Architecture of Resistance Dissemination

Mechanisms of Genetic Exchange

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) enables bacteria to acquire resistance genes from phylogenetically distinct species, dramatically accelerating the spread of AMR beyond vertical inheritance. The three primary HGT mechanisms operate through distinct molecular pathways with characteristic components and efficiencies.

Conjugation represents the most efficient and clinically significant mechanism for disseminating antibiotic resistance genes among bacteria [24]. This contact-dependent process involves the direct transfer of mobile genetic elements (primarily plasmids) through a specialized conjugation pilus or pore formation between adjacent cells [24]. The molecular machinery typically includes an origin-of-transfer sequence (oriT), relaxase enzyme, and type IV secretion system components that mediate DNA processing and transport. Recent research demonstrates that some plasmids require "helper" plasmids to provide the necessary conjugation machinery in trans [25]. Notably, conjugation occurs at substantial rates even in the absence of antibiotic selective pressure, facilitated by certain non-antibiotic pharmaceuticals like ibuprofen and propranolol through reactive oxygen species generation [25].

Transformation involves the uptake and genomic integration of extracellular DNA from lysed donor bacteria by naturally competent recipient cells [24]. Pathogens such as Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Vibrio cholerae, and Streptococcus pneumoniae efficiently acquire resistance determinants through this mechanism [24]. The process requires a state of genetic competence, typically regulated by quorum-sensing systems, and expression of DNA-binding and transport proteins. Evidence suggests that even traditionally non-competent bacteria like Escherichia coli may undergo natural transformation in specific environments such as the gut [24].

Transduction utilizes bacteriophages as vectors to transfer chromosomal or extrachromosomal DNA between bacterial cells [24]. During the lytic cycle, phage particles occasionally package host DNA instead of viral genomes, creating transducing particles that inject this DNA into subsequent hosts. Generalized transduction can transfer any bacterial gene, while specialized transduction moves specific genomic regions. This mechanism is particularly relevant in Staphylococcus aureus, where phages mediate the transfer of the methicillin resistance gene (mecA) [24]. Recent mouse model studies confirm that transduction significantly contributes to genetic diversity and resistance emergence in gut-colonizing E. coli [24].

Other transfer mechanisms include membrane vesicles (MVs), which are 20-400 nm particles secreted by Gram-negative bacteria that can package and deliver antibiotic resistance genes [24]. Studies confirm that Acinetobacter baumannii and E. coli can transfer β-lactamase genes through MVs [24].

Diagram 1: Pathways of Horizontal Gene Transfer in Bacteria. This diagram illustrates the four primary mechanisms (conjugation, transformation, transduction, and membrane vesicle transfer) by which antibiotic resistance genes disseminate between bacteria, highlighting the genetic materials and specialized structures required for each process.

In Vivo Models for Studying HGT

While traditional knowledge of HGT derives from in vitro studies, recent research emphasizes the critical importance of in vivo models that better mimic realistic conditions in human and animal hosts [24]. The mammalian gastrointestinal tract provides a particularly efficient environment for HGT due to high bacterial density, nutrient availability, and complex microbial community interactions.

Experimental studies using mouse models have demonstrated the transfer of broad host-range plasmids like P3 from Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium to diverse recipient bacteria belonging to the Gammaproteobacteria class, including human gut commensals [25]. This transfer occurred efficiently even without antibiotic selective pressure, highlighting the concerning potential for resistance dissemination in natural environments [25]. The "plasmid paradox" – why bacteria maintain and transfer plasmids without apparent selective advantage – remains an active research area, with hypotheses including unknown fitness benefits or "selfish DNA" behavior [25].

Methodologically, these in vivo studies involve infecting mice with recipient bacterial species followed by donor strains 24 hours later, then monitoring bacterial populations and plasmid transfer frequencies through fecal analysis over several days [25]. Such approaches provide invaluable insights into the dynamics of resistance gene spread in realistic biological contexts, enabling more accurate risk assessment and intervention development.

Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Horizontal Gene Transfer

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Function in HGT Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Plasmids | P3 (streptomycin/sulfonamide resistance), RP4 (broad-host-range), pRSF1010 | Conjugation efficiency, Host range studies | Tracking mobilization, Helper plasmid requirements, Fitness costs [25] |

| Bacterial Strains | Salmonella enterica SL1344, Escherichia coli MG1655, Acinetobacter baumannii | Donor/recipient systems, Persister cell studies | Demonstrating intra-species and inter-genera transfer, Environmental persistence [25] |

| Animal Models | Mouse gastrointestinal model, Galleria mellonella infection model | In vivo HGT dynamics, Host-pathogen interactions | Simulating human infection environments, Studying transfer in realistic conditions [24] [25] |

| Selection Agents | Streptomycin, Sulfonamides, Carbapenems, β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations | Selective plating, Competition assays | Quantifying transfer frequencies, Monitoring plasmid stability and persistence [25] |

| Molecular Tools | PCR primers for resistance genes, Sequencing platforms, Fluorescent reporter tags | Detection and quantification, Molecular characterization | Tracking specific resistance elements, Visualizing transfer events, Phylogenetic analysis [24] |

The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on AMR

Pandemic-Related Setbacks in Antimicrobial Resistance Control

The COVID-19 pandemic fundamentally disrupted global healthcare systems and inadvertently reversed years of progress in combating AMR. According to CDC reports, the United States lost significant ground in controlling antimicrobial resistance during 2020, with nearly 40% of the estimated 29,400 deaths from antimicrobial-resistant infections being healthcare-acquired [21]. The diversion of resources toward pandemic response created ideal conditions for resistant pathogens to flourish unchecked.

Table 4 summarizes the profound impacts of the pandemic on AMR epidemiology and control efforts across healthcare settings.

Table 4: Documented Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Antimicrobial Resistance

| Impact Category | Specific Findings | Magnitude of Change | Primary Contributing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Healthcare-Associated Infections | Resistant hospital-onset infections and deaths | ≥15% increase (2019-2020) [21] | Sicker patients, prolonged device use, staffing shortages, PPE challenges |

| Antifungal Resistance | Candida auris infections | 60% overall increase (2020) [21] | Enhanced transmission in COVID-19 units, strained infection control |

| Carbapenem-Resistant Organisms | NDM gene-mediated infections | 460% increase (2019-2023) [2] [26] | Antibiotic overuse in COVID-19, decreased stewardship oversight |

| Gram-Negative Resistance | ESBL, CRE, MDR Pseudomonas/Acinetobacter | Incidence rate ratio: 1.64 (95% CI: 0.92-2.92) [27] | High antibiotic prescribing despite low bacterial co-infection rates |

| Antibiotic Prescribing | Inpatient COVID-19 management | ~80% of hospitalized patients received antibiotics (2020) [21] [27] | Diagnostic uncertainty, concern for bacterial co-infections |

A comprehensive meta-analysis of 28 studies found that the pandemic likely hastened the emergence and transmission of AMR, particularly for Gram-negative organisms in hospital settings [27]. Although the changes were not always statistically significant in pooled analyses, the consistent direction of effect across diverse healthcare environments confirms a genuine worsening of the AMR landscape attributable to pandemic-related disruptions.

Mechanisms of Pandemic-Driven Resistance Acceleration

Several interconnected mechanisms drove the alarming escalation of AMR during the COVID-19 pandemic:

Inappropriate Antibiotic Use: Despite the viral etiology of COVID-19, antibiotics were prescribed to nearly 80% of hospitalized patients during the initial pandemic waves [21] [27]. This reflected initial diagnostic challenges in distinguishing COVID-19 pneumonia from community-acquired bacterial pneumonia, coupled with concerns about bacterial co-infections. Ceftriaxone and azithromycin were the most frequently prescribed agents, with azithromycin use in nursing homes reaching 150% higher in April 2020 compared to the same month in 2019 [21].

Compromised Infection Prevention and Control: Overwhelmed healthcare systems experienced critical shortages of personal protective equipment, increased patient-to-staff ratios, and reduced capacity for maintaining standard infection control protocols [21] [27]. Outbreak investigations identified numerous instances of antimicrobial-resistant pathogen transmission within COVID-19 units, with CDC and public health partners responding to more than 20 such outbreaks in specialized treatment units [21].

Diverted Public Health Resources: Antimicrobial stewardship programs were deprioritized as clinical staff were redeployed to COVID-19 response duties [21]. Simultaneously, public health personnel were diverted from AMR surveillance and containment activities, creating significant data gaps, with the CDC's Antimicrobial Resistance Laboratory Network receiving and testing 23% fewer specimens in 2020 compared to 2019 [21]. This surveillance breakdown allowed community transmission of resistant organisms to proceed undetected.

Methodologies for Tracking and Predicting AMR Evolution

Experimental Workflow for AMR Surveillance

Systematic monitoring of antimicrobial resistance patterns requires standardized methodologies for data collection, analysis, and interpretation. The following workflow represents best practices for comprehensive AMR surveillance:

Diagram 2: AMR Surveillance and Prediction Workflow. This comprehensive workflow outlines the sequential steps from sample collection through data analysis that enables systematic monitoring of resistance patterns and informed intervention strategies.

Predictive Modeling of Resistance Evolution

The emerging field of evolutionary prediction applies quantitative, systems-based approaches to forecast AMR development. These models integrate multiscale data from microbial evolution experiments to quantify both evolutionary predictability (the existence of a probability distribution of outcomes) and evolutionary repeatability (the likelihood of specific events occurring) [28].

Key considerations for predictive modeling include:

Fundamental Limitations: Evolutionary prediction faces inherent constraints from random mutations, genetic drift, and epistatic interactions that create nonlinear fitness landscapes [28]. The characteristic timescale for prediction (τe) represents the practical horizon beyond which forecasts become unreliable due to accumulating stochasticity and model errors [28].

Promising Approaches: Despite challenges, successful prediction of resistance mutations has been demonstrated in both yeast and bacterial systems. Metabolic fitness landscapes have proven valuable for predicting antibiotic resistance, while in silico mutational scanning has anticipated SARS-CoV-2 antiviral resistance mutations [28]. These approaches leverage high-replicate evolution experiments coupled with whole-genome sequencing to map genotype-phenotype relationships.

Stochastic Population Dynamics: Advanced modeling incorporates resource competition between nongenetically resistant and genetically resistant subpopulations, revealing that nongenetic resistance facilitates survival but paradoxically slows the evolution of genetic resistance [28]. Such insights refine our understanding of resistance trajectories and inform combination therapy strategies.

The integration of quantitative systems biology with real-time surveillance data offers the most promising path toward predictive management of the AMR crisis, potentially enabling preemptive interventions before resistance becomes established in clinical settings.

The convergence of antibiotic misuse, efficient horizontal gene transfer mechanisms, and the disruptive impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has created a perfect storm that continues to accelerate the global antimicrobial resistance crisis. The intricate molecular machinery of plasmid-mediated conjugation, even in the absence of antibiotic selection pressure, underscores the formidable challenge containment presents. Quantitative assessment of antimicrobial use patterns through DDD and DOT metrics provides essential surveillance data, while in vivo models reveal the startling efficiency of resistance gene dissemination in biological environments. The pandemic-related setbacks demonstrate the fragility of previous progress and underscore the need for resilient stewardship programs that can withstand healthcare disruptions. Moving forward, integrating quantitative systems biology approaches with enhanced surveillance methodologies offers the most promising path toward predicting and preempting resistance evolution. For researchers and drug development professionals focused on unrecognized human bacterial pathogens, these insights highlight the critical importance of developing novel antimicrobials that circumvent existing resistance mechanisms while implementing robust infection control practices to limit dissemination. Only through a comprehensive understanding of these interconnected drivers can we hope to mitigate the escalating threat of antimicrobial resistance to global health security.

The paradigm of human bacterial pathogens has shifted dramatically over the past half-century. Since the 1950s, the medical community has faced a continuous emergence of bacterial pathogens, now recognized as a major microbiologic public health threat [29]. These pathogens transcend traditional clinical boundaries, spreading through community and environmental routes while demonstrating a remarkable capacity to establish chronic, persistent infections that evade standard diagnostic and therapeutic interventions. This whitepaper examines the dual threats of community transmission and chronic bacterial infections within the broader context of unrecognized human bacterial pathogens research, addressing critical gaps in our understanding of their epidemiology, pathogenic mechanisms, and detection methodologies.

The emergence of novel bacterial species and more virulent strains of known species represents a significant challenge. Between 1973 and 2010, at least 26 major emerging and reemerging bacterial pathogens have been identified, with most originating either from animal reservoirs (zoonoses) or water sources [29]. This trend continues unabated, complicated by factors including development of new diagnostic tools, increased human exposure due to sociodemographic and environmental changes, and the emergence of more virulent bacterial strains particularly affecting immunocompromised populations [29].

Mechanisms of Community Spread and Persistence

Zoonotic and Environmental Transmission Pathways

Community spread of bacterial pathogens occurs primarily through zoonotic transmission and environmental contamination. Analysis of major emerging bacterial diseases reveals that a significant majority have animal origins or persist in water systems, creating resilient reservoirs that facilitate ongoing human exposure [29]. These transmission pathways enable pathogens to bypass conventional clinical containment measures.

Table: Major Emerging Bacterial Pathogens (1973-2010) and Their Transmission Routes

| Year Emerged | Bacterial Species | Primary Disease Association | Transmission Route |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1973 | Campylobacter spp. | Diarrhea | Zoonosis (poultry, cattle) |

| 1976 | Legionella pneumophila | Lung infection | Water (amoebae) |

| 1982 | Borrelia burgdorferi | Lyme disease | Zoonosis (ticks) |

| 1982 | Escherichia coli O157:H7 | Hemorrhagic colitis | Zoonosis (contaminated food) |

| 1987 | Ehrlichia chaffeensis | Human ehrlichiosis | Zoonosis (ticks) |

| 1992 | Bartonella henselae | Cat-scratch disease | Zoonosis (cats) |

| 2010 | Neoehrlichia mikurensis | Systemic inflammatory response | Zoonosis (ticks) |

Molecular Mechanisms of Chronic Persistence

The establishment of chronic bacterial infections involves sophisticated adaptive mechanisms that allow pathogens to evade host immune responses and antimicrobial treatments. Research on infection-associated chronic illnesses (IACCIs) has revealed multiple persistence mechanisms, including:

- Immune evasion through antigenic variation: Pathogens alter surface proteins to avoid immune recognition.

- Intracellular sequestration: Bacteria establish protected niches within host cells.

- Biofilm formation: Microbial communities encased in extracellular matrix provide physical protection.

- Metabolic dormancy: Reduced metabolic activity decreases antibiotic susceptibility.

Animal model studies of Lyme disease demonstrate that Borrelia burgdorferi can persist following conventional single antibiotic treatments, with combination therapies proving more effective in clearing infection [30]. This suggests that bacterial persistence, rather than continued immune stimulation, may underlie some chronic manifestations.

Diagnostic Challenges and Advanced Detection Methodologies

Limitations of Conventional Diagnostic Approaches

Traditional culture-based methods for bacterial identification and quantification face significant limitations in detecting emerging and chronic pathogens. These methods are inherently slow, with growth times ranging from approximately 1 day for Listeria monocytogenes to 30-50 days for Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis [31]. This diagnostic delay critically impacts patient outcomes, particularly in sepsis where appropriate antibiotic administration within hours significantly reduces mortality [32]. Furthermore, standard biomarkers of sepsis such as procalcitonin, presepsin, and C-reactive protein reflect the host's immune response rather than direct pathogen presence, inevitably causing a time-lag that impedes accurate severity assessment [32].

Advanced Molecular Detection and Quantification Platforms

Novel molecular approaches have emerged to address the limitations of conventional diagnostics, enabling rapid identification and quantification of unknown pathogenic bacteria directly from clinical samples.

Digital PCR for Pathogen Quantification

Digital PCR (dPCR) represents a significant advancement over quantitative PCR (qPCR) for pathogen quantification. Unlike qPCR, which requires calibration curves with known standards, dPCR is based on sample partitioning so that individual nucleic acid molecules undergo end-point PCR amplification in separate partitions. Target concentration is then estimated through Poisson distribution analysis [31]. This approach demonstrates greater robustness and reduced sensitivity to PCR inhibitors compared to qPCR [31].

Comparative studies evaluating dPCR and qPCR for quantifying bacterial pathogens (Listeria monocytogenes, Francisella tularensis, and Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis) found that while both dPCR systems tested (QX200 and QuantStudio 3D) quantified similar bacterial amounts, qPCR showed both over- and under-estimation compared to dPCR [31]. The maximum difference among PCR approaches was <0.5 Log10, while cultural methods underestimated the number of bacteria by one to two Log10 for Francisella tularensis and Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis [31].

Tm Mapping Method for Rapid Identification

The Tm mapping method enables rapid identification and quantification of unknown pathogenic bacteria within four hours of blood collection [32]. This innovative approach combines nested PCR using seven bacterial universal primer sets with melting temperature (Tm) analysis to create species-specific Tm mapping shapes compared against an established database.

The methodology employs a eukaryote-made thermostable DNA polymerase free from bacterial DNA contamination, eliminating false-positive results that plague conventional bacterial universal PCR [32]. For accurate quantification, the method incorporates a standard curve formed by Ct values of quantification standards (E. coli DNA) with known concentrations, with final bacterial concentrations corrected according to the 16S ribosomal RNA operon copy number of the identified pathogen [32].

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Bacterial Pathogen Detection

| Research Reagent | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Eukaryote-made thermostable DNA polymerase | Sensitive bacterial DNA amplification without bacterial DNA contamination | Manufactured using eukaryotic (yeast) host cells; eliminates false positives from reagent contamination [32] |

| Mixed 1st PCR forward primers | Accurate quantification regardless of bacterial species | Combines primers targeting minor sequence variations in 16S conserved region (1:1 ratio) [32] |

| Proteinase K with lysing beads | Maximize DNA extraction efficiency from bacterial cells | Maintains constant extraction efficiency across bacterial species; assists in lysing bacterial cell walls [32] |

| Bacterial universal primer sets (7 sets) | Broad-range detection of pathogenic bacteria | Targets highly conserved regions in bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA gene; enables detection of >100 bacterial species [32] |

| Quantification standards (E. coli DNA) | Absolute quantification reference | Precisely quantified by flow cytometry; enables standard curve generation for conversion of Ct values to bacterial counts [32] |

Tm Mapping Method Workflow for Bacterial Identification

Chronic Bacterial Infections and Host-Pathogen Interactions

Immune Dysregulation in Infection-Associated Chronic Illnesses

Chronic bacterial infections can trigger complex host-mediated responses that persist long after the initial infection. Infection-associated chronic conditions and illnesses (IACCIs) encompass various health consequences that occur after an acute infection, including organ damage, autoimmune conditions, and persistent systemic symptoms such as debilitating fatigue, postexertional malaise, cognitive impairment, and sleep disorders [33].

Research on long COVID and myalgic encephalitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) reveals evidence for immune dysregulation and autoimmunity in infection-triggered chronic illnesses. Studies show correlation between autoantibody levels to the autonomic nervous system and symptom severity in patients with infection-triggered ME/CFS [30]. Approximately 50% of long COVID patients meet diagnostic criteria for ME/CFS, suggesting common mechanistic pathways [30].

Latent Viral Reactivation and Bacterial Coinfections

The role of latent viral reactivation in chronic bacterial illness manifestations represents an emerging research frontier. Evidence suggests that Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) reactivation is associated with long COVID development, with higher EBV titers correlating with more symptomatic phenotypes [30]. Interestingly, cytomegalovirus (EBV) seropositivity demonstrates a protective association, decreasing odds of developing long COVID [30]. This differential effect may stem from distinct immunoregulatory mechanisms employed by these herpesviruses.

Host-Pathogen Interactions in Chronic Infection Development

Research Implications and Future Directions

The growing recognition of chronic bacterial manifestations necessitates re-evaluation of therapeutic approaches. The limitations of single antibiotic regimens for persistent infections highlight the potential need for combination therapies targeting different bacterial persistence mechanisms [30]. Furthermore, the correlation between autoantibody levels and symptom severity suggests potential benefit from immunomodulatory approaches in selected patient populations.

Future research priorities should include:

- International surveillance networks to track emerging bacterial pathogens and their transmission dynamics

- Advanced persistence models to elucidate mechanisms of bacterial chronicity

- Rapid diagnostic implementation to reduce time to targeted antimicrobial therapy

- Host-directed therapies to address immune dysregulation in chronic manifestations

- Biomarker discovery to identify patients at risk for chronic sequelae

The financial allocation for gathering international data on waterborne and zoonotic emerging diseases is increasingly urgent to provide better understanding of their clinical relevance and public health impact [29]. As detection methodologies continue to advance, the number of recognized bacterial pathogens contributing to chronic human illness will likely expand, necessitating ongoing collaboration between clinical, microbiological, and public health disciplines.

The rise of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) represents one of the most pressing global health threats of the 21st century, often described as a "silent pandemic" unfolding outside public view. Bacterial AMR was directly responsible for 1.27 million global deaths in 2019 and contributed to 4.95 million deaths, with recent estimates projecting over 8 million annual resistance-associated deaths by 2050 [34] [20]. This escalating health crisis coincides with a paradoxical trend: the progressive decline in development of new antibacterial treatments. The antibiotic pipeline, once robust during the "golden era" of antibiotic discovery (1940s-1960s) that yielded more than 20 new antibiotic classes, has entered what is now termed an "antibiotic discovery void" [34]. Since 1987, only five novel classes of antibiotics have been marketed, and the clinical pipeline contains alarmingly few innovative agents targeting the World Health Organization's (WHO) most critical priority pathogens [34] [35].

This whitepaper analyzes the complex interplay between scientific innovation barriers and economic disincentives that have created this dangerous innovation gap. Within the broader context of unrecognized human bacterial pathogens research, we examine how existing discovery paradigms have largely failed to address the threat of resistant infections, particularly those caused by Gram-negative bacteria identified in the WHO's 2024 Bacterial Priority Pathogens List [36]. We further explore promising alternative approaches, detailed experimental methodologies for pathogen identification, and essential research tools that may help revitalize the field.

The Current Antibacterial Development Landscape

Quantitative Analysis of the Clinical and Preclinical Pipeline

The antibacterial pipeline remains critically anemic, particularly for innovative agents targeting priority pathogens. Table 1 summarizes the current state of antibacterial agents in development based on WHO's 2024 analysis [37] [38].

Table 1: Current Antibacterial Clinical Development Pipeline (2024 WHO Data)

| Pipeline Category | Number of Agents | Innovative Agents | Targeting WHO Critical Pathogens | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Clinical Pipeline | 90 | 15 | 5 | Down from 97 in 2023 |

| Traditional Antibiotics | 50 | 12 | 4 | Mostly β-lactamase inhibitor combinations |

| Non-traditional Agents | 40 | 3 | 1 | Bacteriophages, antibodies, microbiome modulators |

| Preclinical Pipeline | 232 | ~90% from small firms | N/A | Significant economic hurdles for development |

The decline in innovative candidates is particularly alarming. Of the 32 antibiotics under development to address infections from the Bacterial Priority Pathogens List, only 12 can be considered innovative, with just 4 of these active against at least one WHO 'critical' pathogen [38]. The critical priority category includes carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales, third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Enterobacterales, and rifampicin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis [37]. Since 2017, only 13 new antibiotics have obtained marketing authorization, with just two representing a new chemical class deemed truly innovative [38].

The WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List 2024: A Strategic Framework

The 2024 WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List (BPPL) serves as a critical strategic framework for directing research and development efforts. Developed using a multicriteria decision analysis framework that incorporated eight criteria including mortality, non-fatal burden, incidence, 10-year resistance trends, and antibacterial pipeline status, the list represents the most evidence-based prioritization of bacterial threats [36]. Table 2 outlines the highest priority pathogens from the 2024 BPPL [36].

Table 2: WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List 2024 - Critical and High Priority Pathogens

| Priority Tier | Pathogen | Resistance Profile | Total Score (%) | R&D Urgency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Carbapenem-resistant | 84% | Highest |

| Critical | Acinetobacter baumannii | Carbapenem-resistant | 82% | Highest |

| Critical | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Rifampicin-resistant | 80% | Highest |

| Critical | Escherichia coli | Carbapenem-resistant | 78% | Highest |

| High | Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi | Fluoroquinolone-resistant | 72% | High |

| High | Shigella spp. | Fluoroquinolone-resistant | 70% | High |

| High | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Carbapenem-resistant | 68% | High |

| High | Neisseria gonorrhoeae | Extended-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant | 64% | High |

| High | Staphylococcus aureus | Methicillin-resistant | 62% | High |

The 2024 BPPL highlights the persistent threat of antibiotic-resistant Gram-negative bacteria, which dominate the critical priority tier. Notably, the list also emphasizes the disproportionate burden of community-acquired infections in resource-limited settings, with pathogens like fluoroquinolone-resistant Salmonella and Shigella species ranking as high priority [36].

Economic and Regulatory Barriers to Antibiotic Development

Market Failures in Antibiotic Development

The economic model for antibiotic development is fundamentally broken, creating what has been termed a "market failure" that drives pharmaceutical companies away from this critical field. The root causes are multifaceted:

- Poor Return on Investment: Antibiotics are typically used for short durations (days to weeks), unlike medications for chronic conditions that generate sustained revenue. The direct net present value of an antibiotic is close to zero, with most new antibiotics generating only $15-50 million in annual US sales, far below the estimated $300 million needed for sustainability [35].

- High Development Costs with Low Success Rates: The mean cost for developing systemic anti-infectives is approximately $1.3 billion, matching the average across all drug classes, despite a better Phase 1 to approval success rate (25% versus 14% average) [35]. Post-approval costs add an additional $240-622 million over five years [35].

- Stewardship Versus Commercialization Conflict: Appropriate antibiotic stewardship practices that preserve efficacy by limiting use directly conflict with traditional pharmaceutical commercialization models that rely on widespread use to recoup investment [35].

This economic reality has triggered a massive exodus of major pharmaceutical companies from antibiotic research. Since the 1990s, 18 major pharmaceutical companies have exited the field, with even those maintaining active programs beyond this period—GSK, Novartis, Sanofi, and AstraZeneca—shifting away between 2016 and 2019 [34]. The devastating consequence has been a "brain drain" of specialized expertise, with only approximately 3,000 AMR researchers currently active worldwide [35].

Clinical Trial Challenges and Regulatory Hurdles

Clinical trials for new antibiotics face unique methodological and operational challenges that further complicate development:

- Patient Recruitment Difficulties: Trials for antibiotics targeting resistant infections require specific patient populations that are relatively rare at individual sites. The plazomicin trial against carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales screened 2,000 patients but successfully enrolled only 39, at an estimated cost of $1 million per recruited patient [35].

- Non-inferiority Trial Designs: Antibiotics typically must demonstrate non-inferiority to existing therapies rather than superiority, requiring large sample sizes that increase costs and prolong development timelines [35].

- Operational Complexities: Patients with resistant infections often have comorbidities or receive concomitant antimicrobial drugs, complicating the assessment of treatment benefit for investigational drugs [39].

The lengthy pathway from preclinical development to approval—approximately 10-15 years—combined with these clinical trial challenges creates a perfect storm that deters investment in antibiotic development [40].

Innovative Approaches and Methodologies

Meta-Genomics for Pathogen Discovery and Characterization

The investigation of unrecognized bacterial pathogens requires moving beyond traditional culture-dependent methods, which have significant limitations for novel pathogen discovery. Meta-genomics represents a powerful culture-independent approach for comprehensive pathogen identification and characterization [41]. The experimental workflow, illustrated in Figure 1, enables unbiased detection of previously unknown bacterial pathogens in clinical and environmental samples.

Figure 1: Meta-Genomics Pathogen Discovery Workflow

The meta-genomics workflow involves two primary approaches: untargeted shotgun sequencing of all nucleic acids in a sample, and targeted sequencing of known pathogens. For novel pathogen discovery, the de novo shotgun meta-genomics pipeline is particularly valuable as it enables identification of unknown sequences without relying on reference genomes [41]. Critical steps in this process include:

- Initial Assembly: Using algorithms such as SPAdes, Lasergene, or Flye to generate contiguous sequence blocks ("contigs") from overlapping sequencing reads [41].

- Resolution of Genomic Repeats: Employing long-read sequencing platforms to address repetitive genomic regions that challenge short-read technologies [41].

- Genome Polishing: Running assembled genomes through multiple algorithms (Arrow, FreeBayes, Racon) to correct misassemblies, mismatches, and indels [41].

- Functional Annotation: Comparing polished genomes against known sequence databases using tools like UBLAST to annotate conserved elements and assess phylogenetic relatedness [41].

A critical evaluation of assemblers using mock microbial communities concluded that long-read data alone can generate accurate and complete genomes, with software selection significantly impacting quality. Meta-genomics-specific tools such as metaFlye, Raven, and Canu generally outperform general-purpose assemblers [41].

Multi-Omics and Non-Traditional Therapeutic Approaches

Beyond traditional antibiotics, innovative therapeutic strategies are emerging that offer promising alternatives for tackling resistant infections:

- Bacteriophages and Lysins: Bacteriophages (viruses that infect specific bacteria) and lysins (enzymes that degrade bacterial cell walls) represent precision antibacterial approaches with potentially lower resistance development [37] [35].

- Monoclonal Antibodies: Pathogen-specific antibodies can neutralize bacterial toxins or enhance immune clearance of pathogens, though development costs remain high [37].

- Microbiome Modulation: Fecal-based products for restoring gut microbiota have shown success in preventing recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection, with three such products recently authorized [38].

- Anti-virulence Agents: Rather than killing bacteria, these agents disrupt virulence mechanisms (e.g., toxin production, adhesion, quorum sensing), potentially reducing selective pressure for resistance [35].

- Immune Modulators: Agents that enhance host immune responses to infections represent a complementary approach to direct antibacterial activity [35].

These non-traditional approaches comprised 40 of the 90 agents in the clinical pipeline in the 2024 WHO analysis, indicating growing interest in these alternative modalities [37].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3 details key research reagents and platforms essential for investigating unrecognized bacterial pathogens and developing novel antibacterial strategies.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Bacterial Pathogen Investigation

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Application in Pathogen Research |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas Systems | Gene editing and bacterial identification | Pathogen gene function validation, diagnostic development |

| Bacterial Phenotype Microarrays | High-throughput phenotypic screening | Metabolic profiling, antibiotic susceptibility testing |

| Omics Libraries | Focused compound collections | Screening for novel antibacterial activity |

| CARB-X Compound Libraries | Rationally designed focused libraries | Gram-negative antibacterial drug discovery |

| AR Isolate Bank (CDC/FDA) | Quality-controlled resistant isolates | Preclinical development challenge sets |

| Monoclonal Antibody Platforms | Pathogen-specific antibody generation | Therapeutic and diagnostic applications |

| Bacteriophage Libraries | Diverse phage collections | Phage therapy development |

| Synthetic Biology Toolkits | Genetic circuit construction | Engineered diagnostic and therapeutic bacteria |

| Microbiome Modulators | Defined bacterial consortia | Restorative therapy for infection prevention |

| AI/ML Screening Platforms | Predictive compound screening | Identification of novel antibacterial candidates |

These research tools, many supported by government initiatives like the NIH Chemistry Center for Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria (CC4CARB), provide critical resources for overcoming historical challenges in antibacterial discovery [39]. The CC4CARB specifically focuses on synthesizing and distributing rationally designed, focused libraries free-of-charge to the global scientific community for Gram-negative antibacterial drug discovery programs [39].

Bacterial Resistance Mechanisms and Therapeutic Targeting

Understanding the molecular basis of antibiotic resistance is fundamental to designing effective countermeasures. Figure 2 illustrates the primary mechanisms of bacterial resistance and corresponding therapeutic targeting strategies.

Figure 2: Bacterial Resistance Mechanisms and Corresponding Therapeutic Strategies

The five primary resistance mechanisms—enzymatic inactivation, target modification, efflux pumps, permeability barriers, and biofilm formation—represent evolutionary adaptations that bacteria employ to survive antibiotic exposure. Innovative therapeutic approaches must address these specific mechanisms, often through combination strategies that include both direct antibacterial activity and resistance-countering adjuvants [34] [20].

Addressing the innovation gap in antibiotic development requires a multifaceted approach that combines scientific advancement with economic and policy reforms. Promising pathways include:

- Pull Incentives: Implement market entry rewards and subscription-based payment models that delink antibiotic reimbursement from volume of use, creating sustainable economic models for antibiotic development [35] [39].

- Public-Private Partnerships: Expand initiatives like CARB-X (Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria Biopharmaceutical Accelerator) that provide funding and technical support for early-stage antibacterial research [39].

- Regulatory Modernization: Develop streamlined regulatory pathways for non-traditional antibacterial agents and novel clinical trial designs that efficiently demonstrate efficacy against resistant infections [35] [39].

- Global Coordination: Enhance international collaboration through the Quadripartite Joint Secretariat (FAO, UNEP, WHO, WOAH) to implement a comprehensive One Health approach to AMR that addresses human, animal, and environmental dimensions [20].

- Diagnostic Integration: Accelerate development and deployment of rapid diagnostic tests to enable targeted antibiotic use and facilitate clinical trials for pathogen-specific agents [37].

The second UN High-level Meeting on AMR in 2024 resulted in a political declaration pledging to reduce AMR-associated deaths by 10% by 2030, with calls for catalytic funding of $100 million to help 60% of countries globally secure funds to execute AMR plans by 2030 [34]. Such commitments, if backed by sustained investment and implementation, represent crucial steps toward revitalizing the antibiotic pipeline and securing effective treatments for future generations.

The innovation gap in antibiotic development is both a scientific and economic challenge of unprecedented complexity. By leveraging novel discovery methodologies, embracing non-traditional therapeutic approaches, and implementing sustainable economic models, the global research community can begin to bridge this gap and address the escalating threat of antimicrobial resistance.

Beyond Culture: Advanced Genomic and Molecular Tools for Pathogen Discovery

The study of unrecognized human bacterial pathogens represents a critical frontier in public health and infectious disease research. Conventional, culture-dependent diagnostic methods, long considered the "gold standard," are inherently limited for this task, as they require a priori knowledge of a pathogen to select the appropriate growth conditions and subsequent tests [42] [43]. It is estimated that the cause of severe infections like meningoencephalitis remains unknown in approximately 50% of cases using these traditional methods, significantly hindering clinical management and effective response to emerging threats [44]. This diagnostic ceiling creates a pressing need for hypothesis-free tools that can comprehensively characterize the microbial content of a clinical sample.

Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing (mNGS) is a culture-independent, agnostic sequencing technology that has emerged to meet this challenge. By simultaneously sequencing all nucleic acids (DNA and RNA) in a sample, mNGS allows for the detection and identification of any bacteria, virus, fungus, or parasite present without any prior suspicion [45] [43]. This capability is indispensable for research on unrecognized bacterial pathogens, enabling the discovery of novel organisms, the detection of fastidious or slow-growing bacteria that evade culture, and the accurate characterization of complex polymicrobial infections [44] [46]. As public health crises repeatedly emphasize, the rapid deployment of agnostic diagnostics at the start of an outbreak is a cornerstone of an effective response to emerging pathogens [45].

The mNGS Workflow: From Sample to Result

The journey from a complex clinical sample to actionable pathogen data involves a multi-step process designed to maximize the recovery of microbial signals.

Wet-Lab Experimental Protocol

The following workflow diagram outlines the key stages of the mNGS process, highlighting critical decision points that influence assay performance.

Figure 1: The mNGS Experimental Workflow. This diagram outlines the key stages in a clinical metagenomic next-generation sequencing assay, from sample collection to final bioinformatic analysis, with approximate processing times for optimized protocols [47].

Detailed Methodology for Key Experimental Steps: