Unveiling the Biofilm Matrix: A Comprehensive Guide to AFM Visualization and Analysis

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) has emerged as a pivotal tool for elucidating the nanoscale architecture and mechanical properties of bacterial biofilms, structures critically implicated in chronic infections and antimicrobial resistance.

Unveiling the Biofilm Matrix: A Comprehensive Guide to AFM Visualization and Analysis

Abstract

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) has emerged as a pivotal tool for elucidating the nanoscale architecture and mechanical properties of bacterial biofilms, structures critically implicated in chronic infections and antimicrobial resistance. This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals, detailing the foundational principles of biofilm matrix organization. It explores cutting-edge methodological advances, including automated large-area AFM and machine learning integration, for high-resolution structural and functional mapping. The content further addresses common troubleshooting scenarios in sample preparation and imaging, and validates AFM data through correlation with complementary techniques like confocal Raman microscopy and proteomics. By synthesizing current research and technological innovations, this guide aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to leverage AFM for developing novel biofilm control strategies.

The Architectural Blueprint: Understanding Biofilm Matrix Structure and Components

The biofilm matrix is a complex, dynamic, and functional component of microbial communities, often described as the "house of biofilm cells" [1]. This extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) determines the immediate conditions of life for biofilm microorganisms by affecting its porosity, density, water content, charge, sorption properties, hydrophobicity, and mechanical stability [1]. Within the context of Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) visualization research, understanding the composition and architecture of the EPS is paramount, as it forms the fundamental scaffold that AFM techniques probe and characterize. This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of the biofilm matrix, detailing its multifaceted components, their functional roles, and the advanced methodologies used to quantify and visualize its complex architecture, with particular emphasis on techniques relevant to AFM-based research.

Core Composition of the EPS Matrix

Contrary to common belief, the EPS matrix is not primarily composed of polysaccharides but constitutes a diverse assortment of biopolymers of microbial origin. Archaeal, bacterial, and eukaryotic microbes contribute to this matrix, which comprises a wide variety of proteins, glycoproteins, glycolipids, and surprising amounts of extracellular DNA (e-DNA) [1]. In many environmental biofilms, polysaccharides can actually be a minor component [1]. The matrix is highly hydrated, forming a gelatinous network that keeps biofilm cells together, retains water, and interacts with the environment.

Table 1: Key Components of the Biofilm EPS Matrix and Their Primary Functions [1]

| EPS Component | Chemical Nature | Primary Functional Role in Biofilm |

|---|---|---|

| Neutral Polysaccharides | e.g., Cellulose | Constructive, structural component |

| Charged Polysaccharides | e.g., Alginate (polyanion) | Sorptive; ion exchange, nutrient sequestration |

| Amyloids/Curli Fibrils | Proteinaceous fibrils | Structural component; enhances mechanical stability |

| Extracellular DNA (e-DNA) | Double-stranded DNA | Structural integrity, intercellular connector, gene pool |

| Extracellular Enzymes | e.g., Proteases, glucosidases | Active polymer degradation for nutrient acquisition |

| Membrane Vesicles | Lipid-based nanostructures | Export of enzymes, nucleic acids; biological warfare |

| Lectins | Proteins | Informative; specificity and cellular recognition |

A particularly crucial and often underestimated structural component is extracellular DNA (e-DNA). In Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms, e-DNA is organized in distinct grid-like structures and functions as an intercellular connector [1]. Similarly, in Staphylococcus aureus, genomic DNA released through controlled cell lysis serves as a significant structural component [2]. The release of e-DNA in these species is under genetic control, influenced by quorum-sensing systems and iron regulation [1].

Functional Roles and Matrix Dynamics

The EPS matrix is far more than a static scaffold; it is an activated, dynamic environment that is critical for biofilm resilience and community function. Its roles can be categorized as follows:

Structural Integrity and Stability: The matrix provides mechanical stability by maintaining the spatial arrangement of microbial consortia. This stability is achieved through hydrophobic interactions, cross-linking by multivalent cations, and physical entanglement of the biopolymers [1]. Components like amyloid adhesins and cellulose contribute significantly to the mechanical strength, reinforcing the "house" and enabling synergistic interactions between organisms [1].

Protection and Resource Management: The matrix acts as a protective barrier. Its sorption properties allow for the sequestering of dissolved and particulate substances from the environment, providing a localized nutrient source [1]. Furthermore, it retains extracellular enzymes close to the cells, creating an "activated matrix" that enables efficient degradation of complex polymers [1]. This retention mechanism also contributes to resistance against antimicrobial agents by limiting their diffusion and exposure to cells [3].

Genetic Information Exchange and Communication: Biofilms are ideal environments for horizontal gene transfer due to the close proximity of cells. The EPS matrix facilitates this by maintaining a large and accessible gene pool [1]. Beyond its structural role, e-DNA within the matrix is a reservoir of genetic information. Membrane vesicles, phages, and viruses within the matrix further act as carriers for genetic material, enhancing gene exchange and even participating in "biological warfare" by delivering virulence factors and lytic enzymes [1].

Cellular Coordination: The production and modification of EPS are dynamic processes, often following cyclic patterns and being influenced by interspecies interactions and environmental conditions [1]. This allows the biofilm community to adapt its physical structure and material properties as a survival measure against shear stresses, nutrient availability, and competing organisms [3].

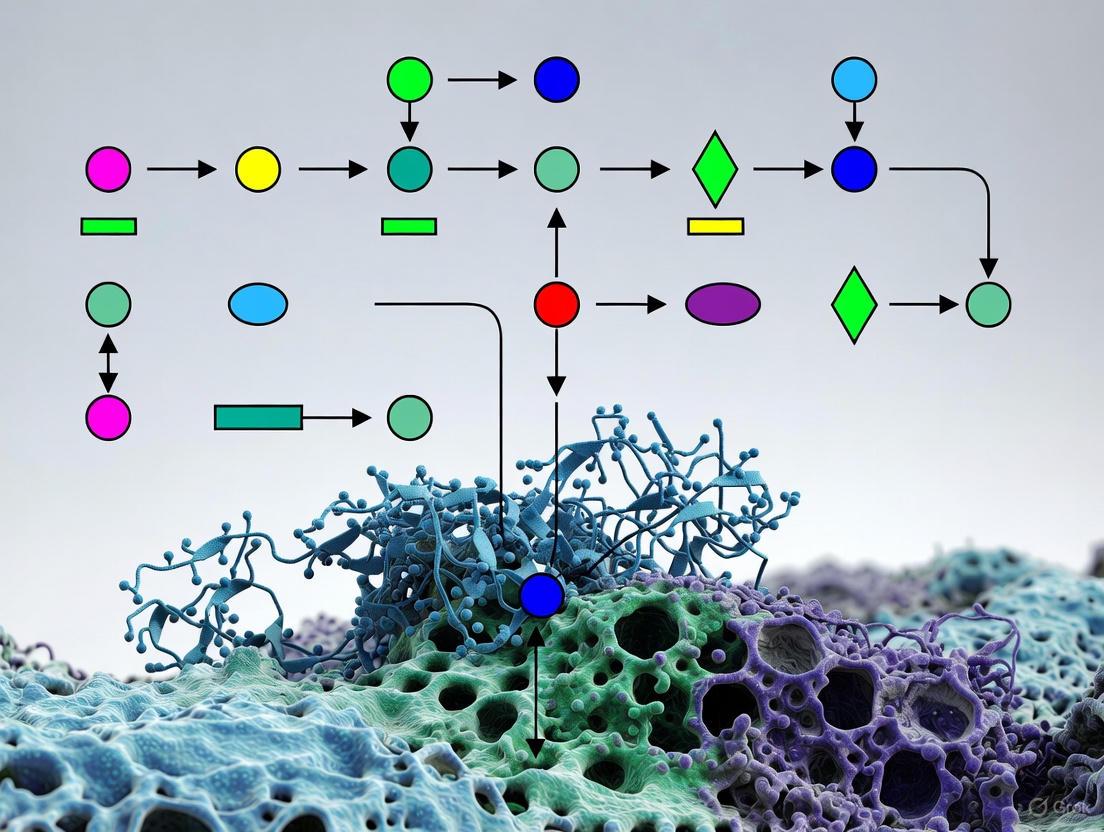

The diagram below synthesizes the core components of the EPS matrix and their integrated functional relationships.

Quantitative Assessment of EPS Components

Accurate quantification of EPS components is essential for evaluating biofilm architecture, response to treatments, and structural integrity. A 2025 study on Staphylococcus aureus provides a robust model for such quantification, using confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) with specific fluorescent stains to measure the reduction in biofilm components after treatment with Tranexamic Acid (TXA) [4].

Table 2: Quantitative Assessment of S. aureus Biofilm Components via CLSM [4]

| Biofilm Component Targeted | Fluorescent Stain / Reagent | Occupied Area in Control (%) | Occupied Area after TXA 10 mg/mL (%) | Reduction Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extracellular Proteins | Sypro Ruby | 17.58 ± 1.22 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 99.2% |

| α-Polysaccharides | Concanavalin A (ConA), Alexa Fluor 633 | 16.34 ± 4.71 | 1.69 ± 0.69 | 89.7% |

| Poly-N-acetylglucosamine | GS-II Lectin, Alexa Fluor 488 | 16.77 ± 1.36 | 0.57 ± 0.28 | 96.6% |

| Bacterial DNA | Propidium Iodide (PI) | 16.55 ± 13.42 | 1.60 ± 0.81 | 90.3% |

| Extracellular DNA (eDNA) | TOTO-1 | 12.43 ± 6.23 | 0.07 ± 0.02 | ≥ 99.0% |

The data demonstrates that all major EPS components were significantly reduced (p < 0.001) by the treatment, with reductions exceeding 89% for all targeted elements [4]. This methodology highlights the efficacy of specific staining reagents for quantifying discrete matrix constituents.

Experimental Protocol: CLSM for EPS Quantification

The following workflow details the protocol for the quantitative assessment of EPS components as described in the aforementioned study [4].

- Biofilm Cultivation: A bacterial suspension (10⁸ CFU/mL) is inoculated into wells of a 24-multiwell plate containing poly-L-lysine-coated glass slides to promote adhesion. The plate is incubated under agitation (150 rpm) for 24 hours at 37°C to form biofilms.

- Treatment and Post-Incubation: After 24 hours, the biofilms are washed with Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) to remove non-adherent cells. The test agent (e.g., TXA) is applied to the treatment wells, while the control wells receive sterile solvent. The plate is then incubated for another 24 hours at 37°C.

- Biofilm Fixation and Permeabilization: Post-treatment, biofilms are washed again with PBS and then treated with a solution containing a detergent (e.g., 0.5% Triton-X 100) and a fixative (e.g., 4% formaldehyde). This step disrupts and fixes the biofilms for subsequent staining.

- Fluorescent Staining: Fixed biofilms are stained with specific fluorescent reagents. The application time for each dye should follow manufacturer recommendations. Examples include:

- Sypro Ruby for extracellular proteins.

- Concanavalin A (ConA) conjugated with Alexa Fluor 633 for α-polysaccharides.

- Griffonia simplicifolia Lectin (GS-II) conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 for poly-N-acetylglucosamine.

- Propidium Iodide (PI) for total bacterial DNA.

- TOTO-1 for extracellular DNA (eDNA).

- CLSM Imaging and Analysis: Stained samples are examined using a Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope. The biofilm depth is measured at intervals (e.g., 4 µm over 80 µm). Images are processed using analysis software (e.g., FIJI/ImageJ), and the density of each component is calculated as the percentage of the occupied area.

Advanced AFM Visualization of Matrix Architecture

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) has emerged as a powerful tool for probing biofilm assembly at the nanoscale, providing insights that are often obscured by other methods. Conventional AFM, however, is limited by small imaging areas (<100 µm), making it difficult to link nanoscale features to the functional macroscale organization of biofilms [5]. A 2025 study introduced an automated large-area AFM approach to overcome this limitation.

Automated Large-Area AFM Protocol

This advanced methodology enables the capture of high-resolution images over millimeter-scale areas, which is critical for understanding spatial heterogeneity [5].

- Sample Preparation: A petri dish containing surface-treated (e.g., PFOTS-treated glass) coverslips is inoculated with the bacterial strain (e.g., Pantoea sp. YR343) in a liquid growth medium.

- Controlled Incubation and Harvesting: At selected time points (e.g., 30 minutes for initial attachment, 6-8 hours for cluster formation), a coverslip is removed, gently rinsed to remove unattached cells, and dried prior to imaging.

- Automated Large-Area Scanning: An AFM system equipped with automated stage control performs sequential high-resolution scans over a predefined, large grid pattern on the sample surface.

- Machine Learning-Assisted Analysis: Machine learning (ML) algorithms are employed for two primary purposes:

- Image Stitching: Seamlessly combines hundreds of individual AFM scans into a single, high-resolution mosaic image of the millimeter-scale area, even with minimal feature overlap between scans.

- Image Segmentation and Classification: Automates the detection, classification, and quantitative analysis of features within the large-area scan. This includes extracting parameters such as cell count, confluency, cell shape, orientation, and the presence of appendages.

- Structural and Mechanical Characterization: The high-resolution capability of AFM allows for the visualization of fine structures like flagella (20–50 nm in height) and the honeycomb patterns formed by cellular clusters. Furthermore, AFM can map nanomechanical properties such as stiffness and adhesion under physiological conditions.

This integrated approach reveals structural intricacies critical for biofilm development, such as flagellar coordination and cellular orientation, which were previously difficult to capture comprehensively [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

The following table catalogues essential reagents, materials, and instruments used in the advanced characterization of biofilm EPS, as cited in this guide.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Biofilm EPS Analysis

| Item Name | Specific Example / Model | Primary Function in EPS Research |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Stains | Sypro Ruby, TOTO-1, ConA-Alexa Fluor 633, GS-II-Alexa Fluor 488, Propidium Iodide | Selective staining and quantification of specific EPS components (proteins, eDNA, polysaccharides) via CLSM [4]. |

| Surface Coating | Poly-L-Lysine | Promotes and standardizes bacterial adhesion to surfaces (e.g., glass slides) for consistent biofilm growth in vitro [4]. |

| Confocal Microscope | Leica TCS SPE | Generates high-resolution, three-dimensional images of stained biofilms for structural and quantitative analysis [4]. |

| Atomic Force Microscope | Automated Large-Area AFM | Provides nanoscale topographical and mechanical mapping of biofilm surfaces and EPS structure, often under physiological conditions [5]. |

| Image Analysis Software | FIJI (ImageJ) | Open-source platform for processing microscopic images and quantifying biofilm parameters like biomass and component density [4]. |

| Biofilm Dispersant | Tranexamic Acid (TXA) | An antifibrinolytic agent demonstrated to significantly reduce bacterial and extracellular matrix components in S. aureus biofilms [4]. |

| Machine Learning Algorithms | Custom ML for image stitching & segmentation | Automates the analysis of large-area AFM data, enabling cell detection, classification, and feature extraction over millimeter scales [5]. |

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) has emerged as a powerful tool in microbiology, enabling researchers to probe the nanostructure and properties of live microbial cells under physiological conditions. Unlike electron microscopy techniques, AFM requires no staining, labeling, or fixation of specimens and can be performed in buffer solution, preserving native cell structures [6]. This capability is particularly valuable for studying biofilm matrix architecture, as it allows researchers to observe cell surface components directly on living cells at (near) molecular resolution, including polysaccharides, peptidoglycan, teichoic acids, pili, flagella, and crystalline protein layers [6]. The technique operates by sensing the minute forces acting between a sharp tip and the sample surface, with a force sensitivity on the order of a few piconewtons (1 pN = 10⁻¹² N) [6]. This exceptional sensitivity enables researchers to probe single receptor-ligand bonds or unfold single proteins, as such single-molecule measurements typically require forces in the 50 to 250 pN range [6].

Within the context of biofilm matrix architecture research, AFM provides unique capabilities for understanding the complex and heterogeneous extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) that characterize multicellular microbial communities [5]. Biofilms are ubiquitous in natural, industrial, and clinical environments, playing critical roles in various ecosystems while posing significant challenges in healthcare due to their resilience against antibiotics and disinfectants [5]. The inherent heterogeneous and dynamic nature of biofilms, characterized by spatial and temporal variations in structure, composition, density, metabolic activity, and microenvironmental conditions, has made complete understanding of their assembly mechanisms challenging [5]. AFM addresses these challenges by enabling detailed investigation of cell structures, cell-to-cell interactions, and finer features like cell walls and appendages at the nanoscale without extensive sample preparation [5].

AFM Fundamentals and Operational Modes

Basic Principles and Instrumentation

Atomic force microscopy functions by scanning a sharp probe mounted on a flexible cantilever across the surface of a sample while measuring the forces between the probe and the sample [5]. A piezoelectric scanner allows high-resolution three-dimensional positioning of the tip relative to the sample [6]. The cantilever deflects in response to tip-sample interactions, and this deflection is quantified using a laser beam reflected from the free end of the cantilever into a photodiode detector [6]. This fundamental operating principle enables AFM to generate detailed topographical images of cell surfaces while simultaneously providing quantitative information about surface forces and mechanical properties [7]. The ability to operate in liquid environments makes AFM particularly suited for investigating biological specimens in conditions that mimic their native physiological states.

Key Imaging and Spectroscopy Modes

AFM offers several operational modes specifically valuable for biofilm research, with the two primary modes being imaging and force spectroscopy. In the imaging mode, the tip follows the contours of the cell in solution to generate a three-dimensional image of the cell surface architecture with (near) molecular resolution [6]. This enables microbiologists to visualize the organization and dynamics of microbial cell walls and appendages at unprecedented detail, answering pertinent questions that could not be addressed before [6]. In force spectroscopy mode, the tip is approached toward and retracted from the sample while measuring the cantilever deflection, which records the interaction force as a function of separation distance [6]. This yields force-distance curves that provide key information on the localization, binding strength, and mechanics of cell surface molecules [6].

Two specialized forms of force spectroscopy have proven particularly valuable in microbiology. Single-molecule force spectroscopy (SMFS) uses tips functionalized with specific biomolecules to probe individual receptor-ligand bonds or to unfold single proteins [6]. Single-cell force spectroscopy (SCFS) replaces the tip with a living cell to probe single-cell adhesion forces [6]. These techniques enable researchers to quantitatively map cell surface structure, properties, and interactions with piconewton sensitivity, providing insights into the fundamental mechanisms governing bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation [6] [7].

Table 1: Key AFM Operational Modes in Biofilm Research

| Mode | Primary Function | Spatial Resolution | Key Measurements | Applications in Biofilm Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topographical Imaging | Surface morphology mapping | (Near) molecular resolution [6] | 3D surface architecture, structural dynamics [6] | Visualization of cells, flagella, EPS, and surface features [6] [5] |

| Single-Molecule Force Spectroscopy (SMFS) | Single-bond interactions | Molecular scale [6] | Binding strength, mechanical properties, molecular unfolding [6] | Probing specific ligand-receptor pairs, polymer mechanics [6] |

| Single-Cell Force Spectroscopy (SCFS) | Cellular adhesion measurement | Cellular scale [6] | Adhesion forces, cell-surface and cell-cell interactions [6] | Quantifying bacterial adhesion to surfaces and other cells [6] [7] |

Nanoscale Visualization of Biofilm Components

Cell Surface Architecture

AFM imaging has provided groundbreaking insights into the three-dimensional organization of bacterial cell walls, particularly the arrangement of peptidoglycan—the main constituent that provides mechanical strength, determines cell shape, and serves as a target for antibiotics [6]. Despite its crucial functional roles, the 3D organization of peptidoglycan has long been controversial [6]. AFM studies have revealed that bacterial species exhibit a variety of peptidoglycan architectures. In Bacillus subtilis, the inner surface of the cell wall showed 50-nm-wide peptidoglycan cables running parallel to the short axis of the cell, with cross striations averaging 25 nm periodicity along each cable [6]. This data supported an architectural model where glycan strands form a peptidoglycan rope coiled into a helix to form inner surface cable structures [6].

In the spherical bacterium Staphylococcus aureus, AFM combined with fluorescent vancomycin labeling revealed concentric rings and knobbly surface structures attributed to nascent and mature peptidoglycan, respectively [6]. These peptidoglycan features were suggested to demarcate previous divisions and potentially hold information specifying the next division plane [6]. Studies of ovoid bacteria (ovococci) showed a preferential orientation of the peptidoglycan network parallel to the short axis of the cells [6], while the rod-shaped Gram-negative Escherichia coli featured peptidoglycan structures running parallel to the plane of the sacculus but in many directions relative to the long axis, with bands of porosity running circumferentially around the sacculi [6].

Beyond peptidoglycan, AFM has enabled visualization of other critical cell surface components. Glycopolymers such as capsular polysaccharides and teichoic acids have been imaged at unprecedented resolution [6]. AFM studies of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG revealed a rough surface morphology decorated with nanoscale waves, which were identified as extracellular polysaccharides since they were largely absent in mutants impaired in exopolysaccharide production [6]. Combined AFM and fluorescence microscopy has mapped the distribution of wall teichoic acids (WTAs) in Lactobacillus plantarum, demonstrating their requirement for proper cell elongation and division [6].

Flagella and Appendages

AFM's high-resolution capabilities have proven particularly valuable for visualizing bacterial flagella and other appendages critical for biofilm formation. Recent studies using automated large-area AFM have examined the organization of Pantoea sp. YR343 on surface treatments, revealing a preferred cellular orientation among surface-attached cells forming a distinctive honeycomb pattern [5]. High-resolution AFM imaging clearly visualized flagellar structures around the cells, measuring approximately 20–50 nm in height and extending tens of micrometers across the surface [5]. These detailed visualizations are critical as appendages like flagella are essential for biofilm development, surface attachment, and motility [5].

The identification of these nanostructures as flagella was confirmed using a flagella-deficient control strain, which showed no similar appendages under AFM [5]. In Pantoea sp. YR343, AFM revealed flagellar structures bridging gaps between cells during early attachment and development phases [5]. Without high-resolution imaging, such structural intricacies would remain obscured, highlighting AFM's unique value in elucidating the nanoscale architecture of bacterial appendages and their role in community organization.

Extracellular Polymeric Substances (EPS)

The extracellular polymeric matrix represents one of the most complex and critical components of biofilms, providing structural stability, protection, and functional capabilities to microbial communities. AFM has enabled researchers to visualize and characterize these heterogeneous matrices with unprecedented detail. Fine EPS structures, including polysaccharides, proteins, and nucleic acids that bind the biofilm together, can be visualized with high clarity using AFM [5]. This high-resolution imaging reveals how these components interact to provide structural stability and protection to the bacterial community [5].

When operated in liquids, AFM preserves the native state of cells and can measure mechanical properties like stiffness, adhesion, and viscoelasticity [5]. These capabilities have been leveraged to study the contribution of specific matrix components to biofilm mechanical properties. For example, studies of Escherichia coli UTI89 pellicles (biofilms at the air-liquid interface) have demonstrated that curli amyloid fibers enhance the strength, viscoelasticity, and resistance to strain of biofilms [8]. Pellicles formed under conditions that upregulate curli production exhibited increased strength and viscoelastic properties as well as greater ability to recover from stress-strain perturbation [8].

Table 2: Nanoscale Properties of Biofilm Components Visualized by AFM

| Biofilm Component | Key Structural Features Revealed by AFM | Dimensions/Properties | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peptidoglycan | Species-dependent architecture: cables, concentric rings, porous networks [6] | 50-nm-wide cables with 25-nm periodicity in B. subtilis [6] | Mechanical strength, cell shape determination, antibiotic targeting [6] |

| Flagella | Filamentous appendages, cell-cell bridging structures [5] | 20-50 nm height, extending tens of micrometers [5] | Surface attachment, motility, early biofilm assembly [5] |

| Extracellular Polysaccharides | Nanoscale waves, rough surface morphology [6] | Feature size varies by species and mutant status [6] | Protection, cellular recognition, biofilm formation [6] |

| Curli Amyloid Fibers | Enhanced viscoelastic network in E. coli biofilms [8] | Increased strength and strain recovery in pellicles [8] | Biofilm robustness, resistance to mechanical disruption [8] |

Advanced AFM Methodologies for Biofilm Research

Large-Area Automated AFM with Machine Learning

Traditional AFM has been limited by small imaging areas (typically <100 μm) restricted by piezoelectric actuator constraints, making it difficult to capture the full spatial complexity of biofilms and raising questions about data representativeness [5]. Recent advances have addressed this limitation through automated large-area AFM approaches capable of capturing high-resolution images over millimeter-scale areas, aided by machine learning for seamless image stitching, cell detection, and classification [5]. This approach provides a detailed view of spatial heterogeneity and cellular morphology during early biofilm formation stages that were previously obscured [5].

Machine learning and artificial intelligence are transforming AFM by enhancing data acquisition, control, and analysis. ML applications in AFM fall into four key areas: sample region selection, scanning process optimization, data analysis, and virtual AFM simulation [5]. AI-driven models optimize scanning site selection, reducing human intervention and accelerating acquisition [5]. These advancements significantly enhance AFM's efficiency, accuracy, and automation, particularly in biological research [5]. For biofilm studies specifically, large-area AFM has enabled researchers to identify preferred cellular orientation patterns, such as the distinctive honeycomb arrangement observed in Pantoea sp. YR343 biofilms [5].

Correlated AFM-Fluorescence Microscopy

To obtain a more complete view of cellular structures, researchers have developed correlated AFM-fluorescence imaging approaches [6]. This integration allows researchers to combine the molecular specificity of fluorescence tagging with the nanoscale resolution of AFM topography, providing complementary information about the spatial distribution of specific biomarkers relative to structural features. For example, this approach has been used to map the distribution of wall teichoic acids in Lactobacillus plantarum while simultaneously visualizing overall cell morphology at high resolution [6].

The combination of AFM with other analytical techniques has further expanded its utility in biofilm research. AFM has been integrated with various non-invasive chemical imaging and composition mapping techniques, internal hydration property measurements of single bacterial endospores, and characterization of outer membrane extensions of bacteria [5]. These multimodal approaches enable comprehensive characterization of biofilm properties across multiple scales and parameters, linking nanoscale structure with chemical composition and functional capabilities.

Quantitative Mechanical Property Mapping

Beyond topographical imaging, AFM enables quantitative mapping of nanomechanical properties across biofilm surfaces [5]. This capability allows researchers to characterize mechanical heterogeneities within biofilms that correlate with structural features and compositional variations. By measuring properties such as stiffness, adhesion, and viscoelasticity, researchers can link matrix composition to mechanical function [5]. For example, studies have shown that curli amyloid fibers in E. coli biofilms significantly enhance viscoelastic properties and improve recovery from mechanical strain [8].

Interfacial rheological measurements during biofilm formation at the air-liquid interface have provided sensitive quantitative parameters that reveal distinct stages during bacterial colonization, aggregation, and eventual pellicle formation [8]. These measurements have demonstrated that pellicles forming under conditions that upregulate curli production exhibit increased strength and viscoelastic properties [8]. Such quantitative mechanical data are essential for understanding how biofilms withstand environmental stresses and resist mechanical removal, with significant implications for combating persistent biofilm-related infections.

Experimental Protocols for AFM Biofilm Characterization

Sample Preparation for Bacterial Biofilm AFM

Proper sample preparation is critical for successful AFM imaging of biofilms while preserving native structure. The following protocol has been successfully employed for studying bacterial adhesion and early biofilm formation:

Substrate Selection and Preparation: Use freshly cleaved mica or glass coverslips as imaging substrates. For hydrophobic surfaces, treat coverslips with PFOTS (perfluorooctyltrichlorosilane) to create uniform hydrophobic surfaces [5]. Silicon substrates with modified surface properties can also be used to study how surface chemistry influences bacterial adhesion [5].

Biofilm Growth and Attachment: Inoculate Petri dishes containing prepared substrates with bacterial cultures in appropriate growth medium. For Pantoea sp. YR343 studies, surfaces were incubated with bacterial cultures for selected time points (e.g., ~30 minutes for initial attachment studies, 6-8 hours for cluster formation) [5].

Sample Rinsing and Stabilization: After incubation, gently rinse substrates with appropriate buffer (e.g., phosphate-buffered saline or growth medium without nutrients) to remove unattached cells while preserving biofilm architecture [5]. Avoid excessive shear forces that could disrupt delicate structures.

Imaging Environment Setup: For liquid imaging, place the sample in the AFM fluid cell and add appropriate buffer solution to maintain physiological conditions. For in situ monitoring of biofilm development, continuous flow systems can be implemented to maintain nutrient supply and waste removal during extended imaging sessions.

Single-Molecule Force Spectroscopy on Extracellular Polymers

SMFS enables researchers to probe the mechanical properties and interaction forces of individual matrix components. The following protocol outlines the key steps for SMFS experiments on bacterial surface polymers:

AFM Tip Functionalization:

- For polysaccharide detection: Functionalize tips with specific lectins using appropriate crosslinkers (e.g., PEG linkers) [6].

- For peptidoglycan recognition: Use vancomycin-modified tips to target D-Ala-D-Ala sites or LysM-modified tips to target specific peptidoglycan binding motifs [6].

- Verify functionalization efficiency through force spectroscopy on control surfaces.

Force Measurement Parameters:

- Set approach/retraction speed to 500-1000 nm/s for most polymer stretching experiments.

- Apply minimal contact force (100-200 pN) and short contact time (0.1-0.5 s) to reduce multiple interactions.

- Collect sufficient force curves (typically 1000-3000 per sample area) for statistical significance.

Data Analysis:

- Identify specific unbinding events or polymer stretching patterns in force-distance curves.

- Calculate adhesion forces, rupture lengths, and stiffness values from representative curves.

- Generate adhesion force maps by correlating force parameters with spatial location.

Controls and Validation:

- Perform experiments on mutant strains lacking specific polymers to confirm binding specificity.

- Use competitive inhibition with free ligands to verify interaction specificity.

- Compare results with biochemical and genetic data to ensure biological relevance.

Large-Area AFM Imaging with Automated Analysis

The implementation of large-area AFM with machine learning assistance requires specific methodological considerations:

Automated Image Acquisition:

- Program the AFM to automatically acquire multiple adjacent images with minimal overlap (5-10%).

- Implement focus and drift correction algorithms to maintain image quality during extended acquisitions.

- Use machine learning-based region selection to identify optimal scanning areas [5].

Image Stitching and Reconstruction:

- Apply feature-based or intensity-based stitching algorithms to combine individual images into seamless large-area maps.

- Use stage coordinates as initial guidance for tile placement.

- Implement blending algorithms to minimize seams at image boundaries.

Machine Learning-Enabled Analysis:

- Train convolutional neural networks for automatic detection and classification of bacterial cells within large-area images.

- Implement segmentation algorithms to quantify cell density, orientation, and distribution patterns.

- Extract morphological parameters (length, width, surface area) for population-level analysis.

Multi-Scale Correlation:

- Correlate large-area AFM maps with optical microscopy images to bridge resolution gaps.

- Combine with chemical imaging techniques (e.g., Raman microscopy) to link structure with composition.

- Integrate mechanical property mapping with topological data for comprehensive characterization.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for AFM Biofilm Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in AFM Experiments | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Imaging Substrates | Freshly cleaved mica, PFOTS-treated glass, silicon wafers [5] | Provide flat, uniform surfaces for bacterial attachment and high-resolution imaging | Studying adhesion dynamics on surfaces with controlled chemistry [5] |

| Functionalization Reagents | Lectins, vancomycin, LysM motifs, PEG crosslinkers [6] | Modify AFM tips for specific molecular recognition in SMFS experiments | Mapping peptidoglycan distribution with vancomycin tips [6] |

| Bacterial Culture Media | YESCA broth, Modified Postgate's Medium C [8] [7] | Support bacterial growth and biofilm formation under controlled conditions | Culturing sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) and uropathogenic E. coli [7] [8] |

| Chemical Modulators | DMSO, Ethanol [8] | Regulate production of specific matrix components (e.g., curli amyloid fibers) | Enhancing curli production in E. coli for mechanical property studies [8] |

Quantitative Data in AFM Biofilm Research

Adhesion Force Measurements

AFM force spectroscopy provides quantitative data on the adhesion forces between bacterial cells and surfaces, which are crucial for understanding initial biofilm formation. Studies using single-cell force spectroscopy have revealed that adhesion forces can vary significantly depending on bacterial species, surface properties, and environmental conditions. Research on sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) demonstrated that the force between the AFM tip and bacterial cell surface remained at a relatively constant level of -3.9 to -4.3 nN over the cell body, with lower adhesion forces (-2.5 to -3.2 nN) detected at the cell-cell interface and higher forces (-4.5 to -6.8 nN) at the periphery of the cell-substratum contact surface [7]. These measurements provide insight into the distribution of adhesive compounds across the cell surface and their role in surface attachment and cell-cell cohesion.

Spatially resolved force mapping has further revealed heterogeneities in adhesion forces across individual cells, correlating with the distribution of specific surface structures and polymers. For example, SMFS with functionalized tips has identified variations in polysaccharide and peptidoglycan exposure across different bacterial strains and growth conditions [6]. In Lactococcus lactis, vancomycin-functionalized tips detected D-Ala-D-Ala sites of peptidoglycan predominantly on equatorial rings, suggesting regions of newly formed peptidoglycan insertion [6]. Similarly, LysM-modified tips revealed anisotropic peptidoglycan bands running parallel to the short axis of mutant cells lacking surface exopolysaccharides [6].

Mechanical Properties of Biofilm Matrix Components

The mechanical characterization of biofilm matrices and their individual components has provided important insights into structure-function relationships in microbial communities. AFM-based rheological measurements have quantified how specific matrix components contribute to overall biofilm mechanical properties. Studies of E. coli pellicles have demonstrated that curli amyloid fibers significantly enhance biofilm strength and viscoelasticity [8]. Pellicles formed under conditions that upregulate curli production (e.g., with 4% DMSO or 2% ethanol) exhibited increased interfacial elasticity and greater ability to recover from mechanical strain compared to untreated biofilms [8].

The mechanical properties of individual matrix polymers have also been characterized through single-molecule force spectroscopy. Polysaccharides, proteins, and nucleic acids each exhibit characteristic mechanical responses to applied forces, providing signatures for identifying these components in complex matrices. For example, the forced unfolding of proteins produces characteristic sawtooth patterns in force-extension curves, while polysaccharides often exhibit entropic elasticity patterns. These mechanical fingerprints enable researchers to identify specific polymer types within heterogeneous biofilm matrices based on their nanomechanical properties.

Table 4: Quantitative AFM Measurements in Biofilm Research

| Measurement Type | Typical Values | Significance | Experimental Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Adhesion Forces | -2.5 to -6.8 nN (SRB) [7] | Determines initial surface attachment strength | Measured between AFM tip and cell surface in liquid [7] |

| Single-Molecule Interactions | 50-250 pN for receptor-ligand bonds [6] | Quantifies specific molecular recognition events | SMFS with functionalized tips [6] |

| Flagellar Dimensions | 20-50 nm height [5] | Reveals appendage structure-function relationships | High-resolution imaging of Pantoea sp. YR343 [5] |

| Cell Clustering Patterns | Honeycomb structures with characteristic gaps [5] | Indicates coordinated community organization | Large-area AFM of early biofilms [5] |

| Polymer Extension Lengths | Varies by polymer type; can extend tens of micrometers [5] | Reflects EPS matrix connectivity and range | SMFS on extracellular polymers [5] |

Future Perspectives in AFM Biofilm Research

The ongoing development of AFM technology continues to expand its applications in biofilm research. Emerging directions include the integration of AFM with other advanced microscopy techniques, such as super-resolution fluorescence microscopy and Raman spectroscopy, to correlate nanoscale structure with specific molecular composition and metabolic activity. These correlative approaches promise to provide more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between biofilm architecture and function. Additionally, the increasing implementation of machine learning and automation in AFM operation and data analysis is transforming how researchers extract biologically meaningful information from complex nanoscale datasets [5].

Technical innovations in AFM technology itself continue to address current limitations. The development of higher-speed AFM systems enables researchers to capture dynamic processes in real time, revealing the temporal evolution of biofilm structure and matrix assembly. New cantilever designs and detection systems improve force sensitivity and spatial resolution, pushing the boundaries of what can be visualized and measured. These advancements, combined with sophisticated data analysis approaches, position AFM as an increasingly powerful tool for elucidating the fundamental principles governing biofilm organization and function across multiple spatial and temporal scales.

As AFM methodologies continue to evolve, their application to biofilm research promises to yield new insights into the complex interplay between individual cells, matrix components, and environmental factors that determine biofilm architecture and properties. These insights will be crucial for developing effective strategies to control harmful biofilms in medical, industrial, and environmental contexts, while potentially harnessing beneficial biofilms for biotechnological applications.

Bacterial biofilms are complex, multicellular communities characterized by their three-dimensional organization and the production of an extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix. A defining feature of these communities is their spatial heterogeneity—the non-uniform distribution of cellular phenotypes, metabolic activities, and matrix components throughout the biofilm structure. This heterogeneity manifests at multiple scales, from the microscopic arrangement of individual cells to the macroscopic organization of metabolic zones, and is crucial for understanding biofilm function and resilience. The architectural complexity of biofilms confers significant survival advantages, including enhanced tolerance to antimicrobials and protection from environmental stresses [9].

Understanding this spatial organization requires advanced analytical techniques capable of resolving structures from the nanometer to millimeter scale. Traditional imaging methods often fail to capture the full scope of this complexity, creating a critical gap in our ability to link local cellular-scale features with the emergence of functional biofilm architectures. This technical limitation has hindered progress in elucidating the fundamental principles governing biofilm assembly and function [5]. Recent advances in atomic force microscopy (AFM), particularly automated large-area AFM integrated with machine learning, now provide unprecedented capability to visualize and quantify biofilm heterogeneity across previously inaccessible spatial scales, offering new insights into patterns such as honeycomb cellular arrangements and stratified metabolic zones [5].

Technical Approaches for Visualizing Biofilm Heterogeneity

The analysis of biofilm architecture requires a multi-modal approach, as no single technique can fully capture the structural and chemical complexity of these communities. The integration of complementary methods provides a more comprehensive understanding of spatial heterogeneity.

Advanced Imaging Techniques

Large Area Automated Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM): Conventional AFM offers high-resolution imaging at the nanoscale but is limited by small scan ranges (typically <100 µm). Recent developments in automated large-area AFM overcome this limitation by combining extensive scanning capabilities (millimeter-scale areas) with machine learning algorithms for image stitching, cell detection, and classification. This approach preserves the exceptional resolution of AFM—enabling visualization of fine features like flagella (20-50 nm in height) and extracellular matrix fibers—while capturing macro-scale organizational patterns [5]. The method can be performed under physiological conditions without extensive sample preparation, preserving native biofilm structures.

Complementary Imaging Methodologies:

- Brewster-Angle Microscopy (BAM): Provides sensitive, quantitative parameters for studying biofilm formation at air-liquid interfaces (pellicles), revealing distinct stages during bacterial colonization and aggregation [8].

- Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy: Enables three-dimensional imaging of biofilms but requires fluorescent staining, which may alter native biofilm properties [5].

- Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM): Offers detailed surface imaging but necessitates sample dehydration and metallic coatings, potentially introducing structural artifacts [5].

Analytical and Computational Methods

- Interfacial Rheometry: Measures viscoelastic properties of biofilms, providing quantitative data on mechanical characteristics such as elasticity, strength, and ability to recover from stress-strain perturbations [8].

- Machine Learning Integration: AI-driven models automate the analysis of large-area AFM data, enabling efficient segmentation, classification of cellular features, and extraction of quantitative parameters including cell count, confluency, shape, and orientation across millimeter-scale areas [5].

Table 1: Key Techniques for Analyzing Biofilm Spatial Heterogeneity

| Technique | Spatial Resolution | Key Measurable Parameters | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large Area Automated AFM | Nanoscale to millimeter-scale | Cellular morphology, orientation, flagellar interactions, surface roughness | High resolution under physiological conditions, minimal sample preparation | Limited to surface features, requires specialized equipment |

| Brewster-Angle Microscopy (BAM) | Micrometer-scale | Surface aggregation kinetics, early colonization stages | Label-free, quantitative for air-liquid interface biofilms | Specialized for interfacial studies |

| Interfacial Shear Rheometry | Bulk measurement | Viscoelasticity (G′), strength, strain recovery | Quantitative mechanical properties, correlates with matrix composition | Does not provide spatial information |

| Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy | Sub-micrometer | 3D structure, chemical composition (with staining) | 3D visualization, chemical specificity | Requires fluorescent labeling, potential photodamage |

Honeycomb Patterns: Structural Organization in Early Biofilm Development

The emergence of patterned cellular arrangements represents a fascinating manifestation of spatial heterogeneity in early biofilm development. Research using large-area AFM to investigate Pantoea sp. YR343 biofilm formation on PFOTS-treated glass surfaces has revealed a distinctive honeycomb pattern during early surface colonization [5].

Pattern Formation and Cellular Orientation

After approximately 6-8 hours of surface propagation, bacterial cells form clusters characterized by these honeycomb-like gaps. AFM imaging with high resolution has enabled detailed analysis of this organization, revealing a preferred cellular orientation among surface-attached cells that facilitates this geometric arrangement. Individual rod-shaped cells (approximately 2 µm in length and 1 µm in diameter) align in specific orientations relative to neighboring cells, creating the interconnected network characteristic of honeycomb structures [5]. This patterned organization likely represents an optimal packing configuration that maximizes intercellular interactions while maintaining access to nutrients.

Flagellar Coordination in Pattern Assembly

Beyond initial attachment, flagellar interactions appear to play a crucial role in honeycomb pattern formation. Large-area AFM has visualized flagellar structures bridging gaps between cells during early attachment and development phases. These flagellar appendages (measuring approximately 20-50 nm in height and extending tens of micrometers across surfaces) appear to coordinate cellular positioning and maintain structural integrity during pattern formation [5]. Control experiments with flagella-deficient strains confirm the essential role of these structures in honeycomb pattern development, as mutant strains fail to form these organized arrangements.

Stratified Metabolic Zones: Physiological Heterogeneity in Mature Biofilms

As biofilms mature, spatial heterogeneity extends beyond physical arrangement to encompass metabolic stratification—the organization of physiologically distinct zones within the biofilm depth. This metabolic compartmentalization represents an adaptive response to chemical gradients that form as nutrients and gases diffuse through the EPS matrix.

Gradient Formation and Microenvironment Variation

The extracellular matrix creates diffusion barriers that lead to the establishment of chemical gradients, including:

- Oxygen gradients: From aerobic conditions at the biofilm-fluid interface to anaerobic conditions in deeper regions

- Nutrient gradients: Decreasing concentration profiles from the surface to the attachment substrate

- Metabolic waste gradients: Accumulation of inhibitory compounds in deeper zones

These chemical gradients create distinct microenvironments that drive phenotypic differentiation and metabolic specialization within subpopulations of biofilm-associated cells [9].

Matrix-Mediated Architectural Organization

The EPS composition directly influences the three-dimensional architecture that supports metabolic stratification. Key matrix components include:

- Filamentous protein fibers: Functional amyloids (e.g., curli in E. coli, Fap in P. aeruginosa) and other polymeric proteins provide structural scaffolding and contribute to surface adhesion [9] [8].

- Exopolysaccharides: High-molecular-weight carbohydrate polymers form hydrogels that retain water, provide mechanical stability, and contribute to diffusion limitation.

- Extracellular DNA (eDNA): Nucleic acids from lysed cells contribute to matrix integrity and may facilitate horizontal gene transfer between biofilm cells.

The spatial segregation and ordering of these matrix components creates architectural features such as pores, channels, and localized regions with differing physicochemical properties that further reinforce metabolic stratification [9].

Table 2: Extracellular Matrix Components and Their Roles in Biofilm Architecture

| Matrix Component | Representative Examples | Structural Features | Functional Role in Spatial Organization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Amyloids | Curli (E. coli), Fap (P. aeruginosa) | Cross-β structure, fibrous | Structural maintenance, adhesion, cell-cell interaction, host cell adhesion |

| Pilus-like Fibers | CUP pili (P. aeruginosa), Csu (A. baumannii) | Rod-like structure, zigzag subunit arrangement | Initial surface adhesion, microcolony formation, biofilm structural integrity |

| Amyloid-like Peptides | PSM (S. aureus) | Cross-α structure (PSMα3, PSMβ2) or cross-β (PSMα1, PSMα4) | Structural scaffolding, cytotoxicity, biofilm stability |

| Filamentous Phages | Pf4 (P. aeruginosa) | α-helical coat protein array surrounding ssDNA | Liquid crystalline tactoids, diffusion barrier, antibiotic tolerance |

| Self-Associating Autotransporters | Ag43 (E. coli) | β-helical passenger domain, C-terminal β-barrel | Bacterial aggregation, homotypic inter-cell association |

Experimental Protocols for Analyzing Biofilm Heterogeneity

Large-Area AFM for Spatial Pattern Analysis

Sample Preparation:

- Grow Pantoea sp. YR343 in appropriate liquid growth medium.

- Inoculate Petri dishes containing PFOTS-treated glass coverslips with bacterial culture.

- At designated time points (e.g., 30 min, 6-8 h for honeycomb pattern observation), remove coverslips and gently rinse with buffer to remove unattached cells.

- Air-dry samples before AFM imaging [5].

Imaging Protocol:

- Utilize automated large-area AFM system with millimeter-scale scanning capability.

- Implement machine learning algorithms for selection of scanning sites to minimize human intervention.

- Acquire multiple high-resolution images with minimal overlap (typically 5-10%).

- Apply image stitching algorithms to create seamless composite images.

- Use ML-based segmentation for cell detection, classification, and extraction of quantitative parameters (cell count, confluency, orientation) [5].

Interfacial Rheometry for Mechanical Characterization

Pellicle Formation:

- Grow UTI89 E. coli and isogenic curli mutants in YESCA broth with/without curli-inducing solvents (2-4% DMSO or 2% EtOH) at 26°C without shaking.

- Assess pellicle formation at 24, 48, and 72 hours [8].

Rheological Measurements:

- Use AR-G2 rheometer with du Noüy ring and double-wall Couette Teflon flow-cell apparatus.

- Add diluted bacterial culture to flow-cell apparatus connected to syringe pump for continuous media injection.

- Measure surface elasticity (G′s) and viscoelastic properties over time.

- Perform stress-strain response assays to evaluate mechanical resilience and recovery capacity [8].

Research Workflow for Biofilm Spatial Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biofilm Architecture Studies

| Reagent/Material | Composition/Type | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| PFOTS-Treated Glass | (Perfluorooctyltrichlorosilane) treated glass coverslips | Provides hydrophobic surface for controlled bacterial attachment and biofilm formation |

| YESCA Broth | 0.5 g/L yeast extract, 10 g/L casamino acids | Standard growth medium for pellicle formation assays with E. coli UTI89 |

| DMSO/Ethanol | Dimethyl sulfoxide (2-4%) or ethanol (2%) | Chemical inducers that upregulate curli amyloid fiber production in E. coli |

| Glutaraldehyde/Formaldehyde Fixative | 2% glutaraldehyde, 4% formaldehyde in 0.1 M Na-Cacodylate buffer | Cross-linking fixative for structural preservation in electron microscopy |

| Critical Point Dryer | Liquid CO₂ | Removes residual ethanol from samples while preserving delicate biofilm architecture |

Implications for Drug Development and Therapeutic Strategies

The spatial heterogeneity of biofilms has profound implications for antimicrobial development and therapeutic interventions. The recognition of stratified metabolic zones explains the differential antibiotic efficacy observed in various biofilm regions, where metabolically inactive cells in deeper zones exhibit heightened tolerance to conventional antibiotics that target active cellular processes [9].

The honeycomb pattern observed in early biofilm formation represents a potential intervention target for biofilm prevention. Disrupting the initial organizational cues, such as flagellar coordination or intercellular signaling, could prevent the transition from reversible attachment to structured, resilient biofilm communities [5]. Furthermore, the mechanical properties conferred by specific matrix components, such as the increased strength and viscoelasticity provided by curli amyloids, suggest that targeting these structural elements could enhance biofilm susceptibility to mechanical disruption [8].

Spatial Heterogeneity and Antimicrobial Resistance

The integration of advanced imaging technologies, particularly large-area AFM, with traditional biofilm analysis methods has revealed the complex spatial architecture of bacterial communities with unprecedented clarity. The discovery of highly organized patterns such as honeycomb cellular arrangements and the characterization of stratified metabolic zones provide fundamental insights into the organizational principles of biofilm life. These architectural features directly contribute to the emergent properties of biofilms, including their formidable resistance to antimicrobial agents and environmental stresses.

Future research directions should focus on correlating these spatial patterns with functional outcomes, including antibiotic penetration, immune evasion, and resource utilization. The continued development of computational tools for analyzing spatial heterogeneity, combined with techniques for real-time monitoring of biofilm development under physiological conditions, will further enhance our understanding of these complex communities. This comprehensive understanding of spatial organization from honeycomb patterns to metabolic zonation provides a foundation for developing novel anti-biofilm strategies that specifically target the structural integrity and organizational principles of these resilient microbial communities.

Linking Matrix Architecture to Biofilm Resilience and Antibiotic Tolerance

The architecture of the biofilm matrix constitutes a fundamental determinant of bacterial resilience, directly influencing antibiotic treatment outcomes in chronic and device-associated infections. This whitepaper examines the intricate relationship between matrix structural organization and multidrug tolerance, with a specific focus on insights gained through advanced atomic force microscopy (AFM) visualization. We detail how nanoscale imaging reveals emergent mechanical properties and protective barriers within biofilms that undermine conventional antimicrobial therapies. The technical protocols and analytical frameworks presented herein provide researchers with methodologies to quantify architectural features contributing to treatment failure, thereby informing the development of novel anti-biofilm strategies targeting matrix integrity.

Biofilms are multicellular bacterial communities encased in a self-produced, hydrated matrix of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) that confers significant protection against environmental insults, host immune responses, and antimicrobial agents [10]. This matrix is not merely a passive scaffold but a dynamic, functionally active component that determines the physical integrity and recalcitrance of biofilms. The transition from planktonic to biofilm-based growth represents a major shift in bacterial lifestyle, driven by environmental cues and sophisticated signaling systems, resulting in structured communities where cells exhibit up to a 1,000-fold increase in antibiotic resistance compared to their free-living counterparts [11].

Understanding the precise molecular organization of this matrix has been a longstanding challenge in microbiology. Recent advances in high-resolution imaging technologies, particularly Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM), have begun to unravel the nanoscale architecture that underpins biofilm resilience. Research on Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms, a primary pathogen in cystic fibrosis lung infections, has revealed a filamentous protein meshwork forming the biofilm matrix, with distinct cellular arrangements and macromolecular organization compared to planktonic cells [12]. This structural complexity creates heterogeneous microenvironments that limit antibiotic penetration and promote bacterial persistence, making biofilm-associated infections notoriously difficult to eradicate [13] [14].

Composition and Structural Principles of the Biofilm Matrix

Core Matrix Components

The biofilm matrix is a complex hydrogel composed of a diverse array of biopolymers that vary depending on bacterial species, strain, and environmental conditions. These components form an integrated network that provides both structural stability and protective functions.

Table 1: Core Components of the Biofilm Extracellular Matrix

| Component | Primary Functions | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Extracellular DNA (eDNA) | Initial adhesion, structural integrity, cation chelation, antibiotic binding | Released via cell lysis in many bacterial species [13] [15] |

| Exopolysaccharides | Scaffold formation, adhesion, cohesion, barrier function | Alginate (P. aeruginosa), PIA (S. aureus), cellulose [13] [10] |

| Proteins | Adhesion, structural reinforcement, enzymatic activity | Bap-family proteins, CdrA (P. aeruginosa), amyloids (e.g., curli) [15] [10] |

| Lipids & Surfactants | Hydrophobicity modulation, dispersal, structure modification | Phenol-soluble modulins (PSMs) in S. aureus [13] |

| Water | Hydration, nutrient diffusion, gel formation | Up to 97% of biofilm volume [10] |

These biopolymers do not function in isolation but form a cross-linked network through specific molecular interactions. For instance, eDNA can bind to positively charged segments of cell surface-exposed proteins, while polysaccharides interact with other matrix components to create a cohesive, viscoelastic structure [15] [10]. The resulting matrix can constitute over 90% of the biofilm's dry mass, creating a formidable barrier to antimicrobial penetration [13].

Architectural Principles and Spatial Organization

The spatial arrangement of matrix components follows organizational principles that enhance biofilm stability and function. AFM studies of early bacterial aggregates have revealed that environmental cues and spatial organization alone can be sufficient to enhance mechanical resilience, even before full matrix maturation [16].

High-resolution AFM imaging of Pantoea sp. YR343 biofilms has uncovered a preferred cellular orientation among surface-attached cells, forming a distinctive honeycomb pattern [5]. This highly organized arrangement is facilitated by flagellar coordination that extends beyond initial attachment, suggesting that bacterial appendages play an ongoing role in maintaining architectural integrity. The emerging pattern creates fluid-filled channels and voids that function as a circulatory system, facilitating the distribution of nutrients and removal of waste products throughout the biofilm community [10].

This structural heterogeneity generates varying degrees of porosity and density within the matrix, creating diffusion barriers that restrict antibiotic penetration. The matrix's architectural complexity results in a viscoelastic mechanical profile that allows biofilms to withstand significant shear forces and physical disruption while maintaining their protective function [10] [17].

Mechanisms of Antibiotic Tolerance Linked to Matrix Architecture

Physical Barrier and Impaired Antibiotic Penetration

The dense, cross-linked matrix creates a formidable physical barrier that significantly impedes the penetration of antimicrobial agents. The extracellular polysaccharide (EPS) matrix serves as a primary adaptive mechanism, with bacteria increasing EPS production under stressful conditions, including antibiotic exposure [14]. This reduced penetration represents a fundamental mechanism of biofilm-associated resistance, with factors including increased biofilm thickness, drug diffusion efficacy, and antibiotic concentration and duration all influencing therapeutic outcomes [14].

The anionic nature of many matrix components, particularly eDNA, enables charge-based interactions with antibiotics. Positively charged aminoglycosides, such as tobramycin, can bind to negatively charged eDNA in the matrix, effectively reducing the antibiotic concentration that reaches the bacterial cells [13]. In chronic infections, this effect is amplified when host-derived DNA from neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) forms an additional physical shield that further protects the biofilm from antibiotics and immune components [13]. The slowed diffusion through the EPS matrix also increases the likelihood of antibiotic inactivation by extracellular enzymes before reaching lethal concentrations for embedded cells [14].

Physiological Heterogeneity and Metabolic Adaptation

The architectural complexity of biofilms creates heterogeneous microenvironments with distinct physiological properties. According to the zone model, each bacterium responds to its immediate microenvironment, leading to diverse physiological states within the same biofilm [14]. This spatial organization generates nutrient and oxygen gradients that profoundly influence bacterial metabolism and antibiotic susceptibility.

The deepest layers of biofilms typically experience nutrient-depleted conditions due to consumption by peripheral cells and diffusion barriers [14]. These nutrient-deficient zones promote the emergence of persister cells—dormant, slow-growing variants that exhibit exceptional tolerance to antibiotics [14]. This metabolic stratification means that antibiotics targeting actively growing cells, such as β-lactams, often fail to eradicate the entire biofilm community, allowing for regrowth once antibiotic pressure is removed.

Efflux Pumps and Horizontal Gene Transfer

The heterogeneous bacterial population within biofilms displays distinct patterns of efflux pump gene expression. Research has documented the upregulation of specific antibiotic resistance pumps in the upper regions of biofilms, while different expression patterns occur in deeper zones [14]. In Pseudomonas aeruginosa, hypoxia within dense biofilm regions enhances antibiotic resistance by altering the composition and activity of multidrug efflux pumps [14].

The close proximity of cells within the structured biofilm matrix also facilitates efficient horizontal gene transfer (HGT), allowing for the dissemination of resistance genes [15]. The presence of eDNA in the matrix provides a readily available pool of genetic material for natural transformation, while the structured environment promotes conjugative transfer of plasmids carrying resistance determinants. This combination of physical protection and enhanced genetic exchange makes biofilms significant reservoirs of antibiotic resistance genes [15].

Table 2: Biofilm-Associated Resistance Mechanisms and Architectural Drivers

| Resistance Mechanism | Architectural Driver | Impact on Antibiotic Efficacy |

|---|---|---|

| Limited Antibiotic Penetration | Dense EPS matrix with high polysaccharide content | Reduced antibiotic concentration at target sites [13] [14] |

| Metabolic Heterogeneity | Nutrient and oxygen gradients creating distinct zones | Increased persister cell formation [14] |

| Enhanced Efflux Pump Activity | Zone-specific gene expression patterns | Active extrusion of antibiotics from subpopulations [14] |

| Horizontal Gene Transfer | Close cell proximity within structured communities | Dissemination of resistance genes [15] |

| Enzymatic Inactivation | Trapping of antibiotics within matrix | Antibiotic degradation before reaching cells [14] |

Biofilm Resistance Mechanisms Diagram: This diagram illustrates how biofilm matrix architecture drives multiple mechanisms that collectively contribute to enhanced antibiotic tolerance.

AFM Methodologies for Visualizing Matrix Architecture

Fundamental AFM Principles and Imaging Modalities

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) provides a powerful, multifunctional platform for interrogating biofilm systems at the nanoscale without extensive sample preparation. The technique operates by scanning a sharp probe with a nanometer-scale radius of curvature across a surface while monitoring cantilever deflection via a laser beam reflection [17]. For soft biological samples like biofilms, tapping mode (intermittent contact mode) is preferred as it reduces friction and drag forces that could distort delicate structures [17].

AFM's capability to operate under physiological conditions in liquid environments preserves the native state of biofilm components, enabling researchers to visualize dynamic processes and measure mechanical properties in real time [5] [17]. Simultaneous phase imaging captures data on material properties, providing qualitative distinction between different matrix components based on their mechanical characteristics [17]. This is particularly valuable for differentiating between polysaccharides, proteins, and nucleic acids within the complex biofilm matrix.

Advanced Large-Area AFM and Automated Imaging

Traditional AFM has been limited by small imaging areas (<100 µm), restricting its ability to capture the full spatial complexity of biofilms. Recent advancements address this limitation through automated large-area AFM approaches capable of capturing high-resolution images over millimeter-scale areas [5]. This breakthrough enables researchers to link nanoscale features with macroscale organization, providing a comprehensive view of biofilm architecture.

The implementation of machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) has revolutionized AFM data acquisition and analysis. ML algorithms assist with automated region selection, image stitching, cell detection, and classification, enabling efficient quantitative analysis of microbial communities over extensive areas [5]. These advancements allow for continuous, multi-day experiments without human supervision, capturing dynamic structural changes during biofilm development and in response to antimicrobial challenges [5].

Force Spectroscopy and Nanoindentation

Beyond topographical imaging, AFM can operate as a sensitive force probe to quantify mechanical properties and interaction forces within biofilms. Force spectroscopy measures the deflection of the cantilever as a function of tip-to-sample separation, generating force-distance curves that reflect the chemical and physical properties of the biofilm surface [17].

Operating AFM as a nanoindenter enables measurement of elastic moduli and turgor pressure by comparing force curves obtained on a reference hard surface with those from the softer biofilm sample [17]. The resulting indentation depth versus applied force data can be analyzed using theoretical frameworks, most commonly the Hertz model, to quantify mechanical properties [17]. Studies applying this approach to early P. aeruginosa aggregates have revealed that these structures exhibit increased resistance to deformation compared to planktonic cells, suggesting that environmental cues and spatial organization alone enhance mechanical resilience even before full matrix maturation [16].

Sample Preparation Protocols for AFM Analysis

Proper sample preparation is critical for successful AFM imaging of biofilms, particularly for maintaining structural integrity during analysis. Immobilization techniques can be broadly categorized into mechanical and chemical approaches:

Mechanical Immobilization Protocols:

- Porous Membrane Entrapment: Cells are physically trapped within membranes with pore diameters similar to cell dimensions [17].

- PDMS Microstamping: Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) stamps with customized microstructures are created using silicon wafer masters, enabling controlled immobilization of microbial cells through convective and capillary forces [17].

- Agarose Gel Entrapment: Cells are embedded within low-concentration agarose gels that provide support while allowing nutrient diffusion [17].

Chemical Immobilization Protocols:

- Cation-Mediated Attachment: Addition of divalent cations (Mg²⁺, Ca²⁺) to suitable substrates promotes secure attachment without significant viability reduction [17].

- Poly-L-Lysine Coating: Surfaces treated with poly-L-lysine provide positively charged substrates for cell adhesion [17].

- Cross-linking Agents: Carbodiimide chemistry can create covalent bonds between bacterial surface proteins and appropriately functionalized substrates [17].

Table 3: AFM Operational Modalities for Biofilm Characterization

| AFM Modality | Key Measurements | Applications in Biofilm Research |

|---|---|---|

| Tapping Mode Imaging | Topography, phase imaging | Visualization of matrix structure and component distribution [17] |

| Force Spectroscopy | Adhesion forces, molecular interactions | Measurement of cell-surface and cell-matrix interactions [17] |

| Nanoindentation | Elastic modulus, turgor pressure | Quantification of mechanical properties and stiffness [16] [17] |

| Single-Molecule Force Spectroscopy | Ligand-receptor binding, polymer mechanics | Analysis of specific molecular interactions within matrix [17] |

| Large-Area Automated AFM | Millimeter-scale topography | Correlation of nanoscale features with community architecture [5] |

Emerging Research and Therapeutic Applications

AFM-Enabled Insights into Pathogenic Biofilms

Advanced AFM methodologies are providing unprecedented insights into the structural organization of clinically relevant biofilms. Research on Pseudomonas aeruginosa has visualized a filamentous protein meshwork forming the biofilm matrix, with distinct cellular arrangements compared to planktonic cells [12]. These structural features represent protective elements that underpin antibiotic tolerance and are currently being investigated as potential therapeutic targets.

Studies examining early P. aeruginosa aggregates under physiologically relevant conditions have revealed that these structures exhibit complex architecture and increased resistance to deformation, even in the absence of mature extracellular matrix components [16]. This suggests that physical organization alone may significantly contribute to persistence during chronic infection. The mechanical robustness of these early aggregates, as quantified by AFM force spectroscopy, highlights the importance of targeting the initial stages of biofilm formation before communities become fully established and treatment-resistant [16].

Integration with Complementary Analytical Techniques

AFM is increasingly being integrated with other analytical methods to provide comprehensive multimodal characterization of biofilms. Correlative imaging approaches combine AFM with fluorescence microscopy, allowing researchers to link topological features with specific molecular components identified through fluorescent labeling [5] [10]. This integration is particularly powerful for identifying the spatial distribution of different matrix constituents and their contribution to overall biofilm architecture.

The combination of AFM with spectroscopic techniques such as Raman spectroscopy provides simultaneous topographical and chemical information, enabling characterization of biofilm composition at the single-cell level [10]. These advanced correlative approaches are helping to unravel the complex structure-function relationships that define biofilm resilience and antibiotic tolerance.

Implications for Anti-Biofilm Therapeutic Development

The insights gained from AFM-based structural and mechanical characterization of biofilms are informing novel therapeutic strategies aimed at disrupting matrix integrity. Approaches under investigation include:

- Matrix-Degrading Enzymes: Glycoside hydrolases that break down polysaccharide components and DNases that target eDNA have shown promise in disrupting biofilm integrity and enhancing antibiotic penetration [13].

- Efflux Pump Inhibitors: Compounds that block multidrug efflux pumps have demonstrated potential to reduce biofilm tolerance to antibiotics, particularly in hypoxic zones where efflux activity is enhanced [14].

- Quorum Sensing Inhibitors: Molecules that interfere with bacterial cell-to-cell communication can prevent the coordinated gene expression required for matrix production and biofilm maturation [10].

- Surface Modifications: AFM studies of bacterial adhesion on engineered surfaces are guiding the development of anti-fouling materials that resist biofilm formation on medical devices [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Materials for AFM Biofilm Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| PFOTS-Treated Glass | Creates hydrophobic surface for controlled bacterial adhesion | Studying early attachment dynamics of Pantoea sp. YR343 [5] |

| Synthetic Cystic Fibrosis Sputum Medium (SCFM2) | Mimics in vivo conditions for pathogenic biofilm growth | Culturing P. aeruginosa aggregates for AFM analysis [16] |

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) Stamps | Microstructured surfaces for cell immobilization | Mechanical entrapment for single-cell AFM under physiological conditions [17] |

| Divalent Cations (Mg²⁺, Ca²⁺) | Promotes bacterial adhesion to substrates | Sample preparation for AFM imaging without reducing cell viability [17] |

| Functionalized AFM Tips | Specific molecular interactions measurement | Coating with concanavalin A for polysaccharide mapping [17] |

AFM Biofilm Analysis Workflow: This diagram outlines the key steps in a comprehensive AFM-based analysis of biofilm matrix architecture, from sample preparation to therapeutic application.

The structural architecture of the biofilm matrix represents a critical determinant of antibiotic treatment failure in chronic and device-associated infections. Advanced AFM methodologies now enable researchers to visualize this architecture at unprecedented resolution, revealing nanoscale features that contribute to mechanical resilience and limited antimicrobial penetration. The integration of large-area automated AFM with machine learning analytics and complementary imaging techniques provides a powerful multidisciplinary approach to deciphering the complex structure-function relationships within biofilms.

These technical advances are translating into novel therapeutic strategies that target matrix integrity rather than bacterial viability, offering promising alternatives to conventional antibiotics. As AFM technologies continue to evolve, particularly through enhanced automation and multimodal integration, they will undoubtedly yield further insights into the fundamental principles of biofilm organization and resistance, ultimately informing more effective clinical approaches to combat these resilient microbial communities.

Advanced AFM Modalities: From High-Resolution Imaging to Nanomechanical Mapping